Bacteria Grow Under 400,000 Times Earth's Gravity

Finding increases places alien life may exist, authors say.

Proving that you don't have to be big to be tough, some microbes can survive gravity more than 400,000 times that felt on Earth, a new study says.

Most humans, by contrast, can tolerate forces equal to about three to five times Earth's surface gravity (g) before losing consciousness.

The extreme "hypergravity" of 400,000 g is usually found only in cosmic environments, such as on very massive stars or in the shock waves of supernovas, said study leader Shigeru Deguchi, a biologist at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology.

(Related: "Einstein's Gravity Confirmed on a Cosmic Scale.")

Deguchi and his team were able to replicate hypergravity on Earth using a machine called an ultracentrifuge.

The scientists rapidly spun four species of bacteria—including the common human gut microbe Escherichia coli—to create increasingly intense gravity conditions.

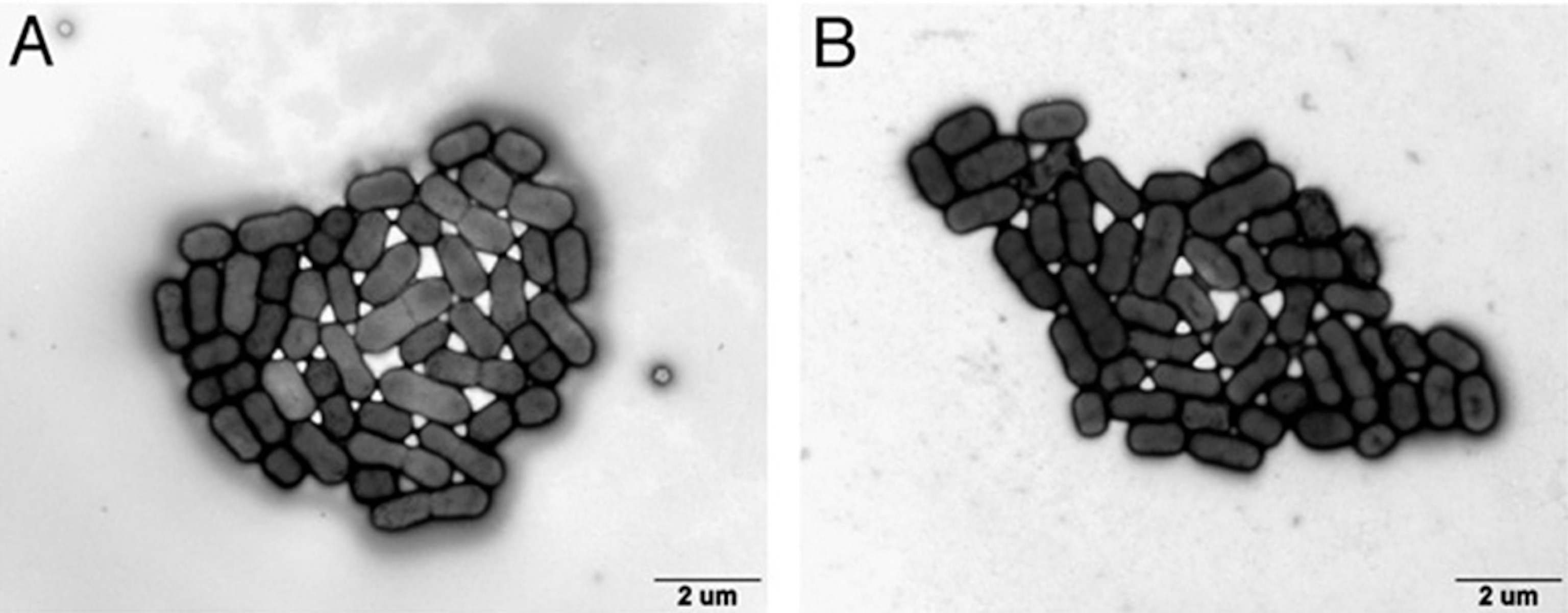

The bacteria clumped together into pellets as the gravity increased, but their forced closeness didn't seem to deter growth: All four species multiplied normally under thousands to tens of thousands of times Earth's gravity.

Two of the species—E. coli and Paracoccus denitrificans, a common soil bacteria—grew under the strain of 403,627 g.

For Extreme Gravity Tolerance, Size Matters

Part of the microbes' ability to withstand hypergravity has to do with their sizes, Deguchi explained.

The larger an organism, the more sensitive it is to gravitational forces. The bodies of multicellular organisms—such as humans—start to collapse and turn to mush under the force of just a few g.

Bacteria are also more biologically suited to extreme gravity conditions, Deguchi said.

Unlike the eukaryotic cells that make up our bodies, bacterial cells don't have specialized structures called organelles. Examples of organelles include cell nuclei, which house the bulk of DNA in humans and other animals, and mitochondria, the energy-production factories of eurkaryotic cells.

When organelles are subjected to hypergravity, they tend to compact, or "sediment," Deguchi said. With their key components tightly jumbled up, the cells basically shut down.

"In contrast, prokaryotic cells [like the ones in the study] do not have organelles and are less sensitive to the sedimentation effect," he said in an email.

(Related: "All Species Evolved From Single Cell, Study Finds.")

Still, the study results suggests some bacterial species withstand hypergravity better than others, and the reasons for this are unclear.

"Further studies are needed to say if certain groups of microbes are more resistant to hypergravity than others," Deguchi said.

Even More Alien Microbes Out There?

The new findings are consistent with an idea called panspermia, which says that life on Earth may be descended from alien microbes that hitched rides to our planet aboard ancient asteroids and comets.

Scientists calculate that pieces of space rock ejected during those early impacts would have been accelerated up to 300,000 g—conditions that it now appears some hitchhiking microbes might have been able to survive.

(Also see "Alien Life Can Survive Trip to Earth, Space Test Shows.")

Still, Deguchi said, "there is no definitive evidence whatever that life exists beyond Earth," and so there's no hard proof for the panspermia theory.

Luckily, the new study also expands the range of places we can look today for alien life—at least in bacterial form, Deguchi added.

For example, scientists estimate that the gravity on brown dwarfs—cosmic bodies with masses between those of Jupiter-like planets and small stars—is about ten to a hundred g.

"If life does exist outside the solar system, then it can live and exploit more places than we previously thought," Deguchi said.

The hypergravity study is detailed in this week's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.