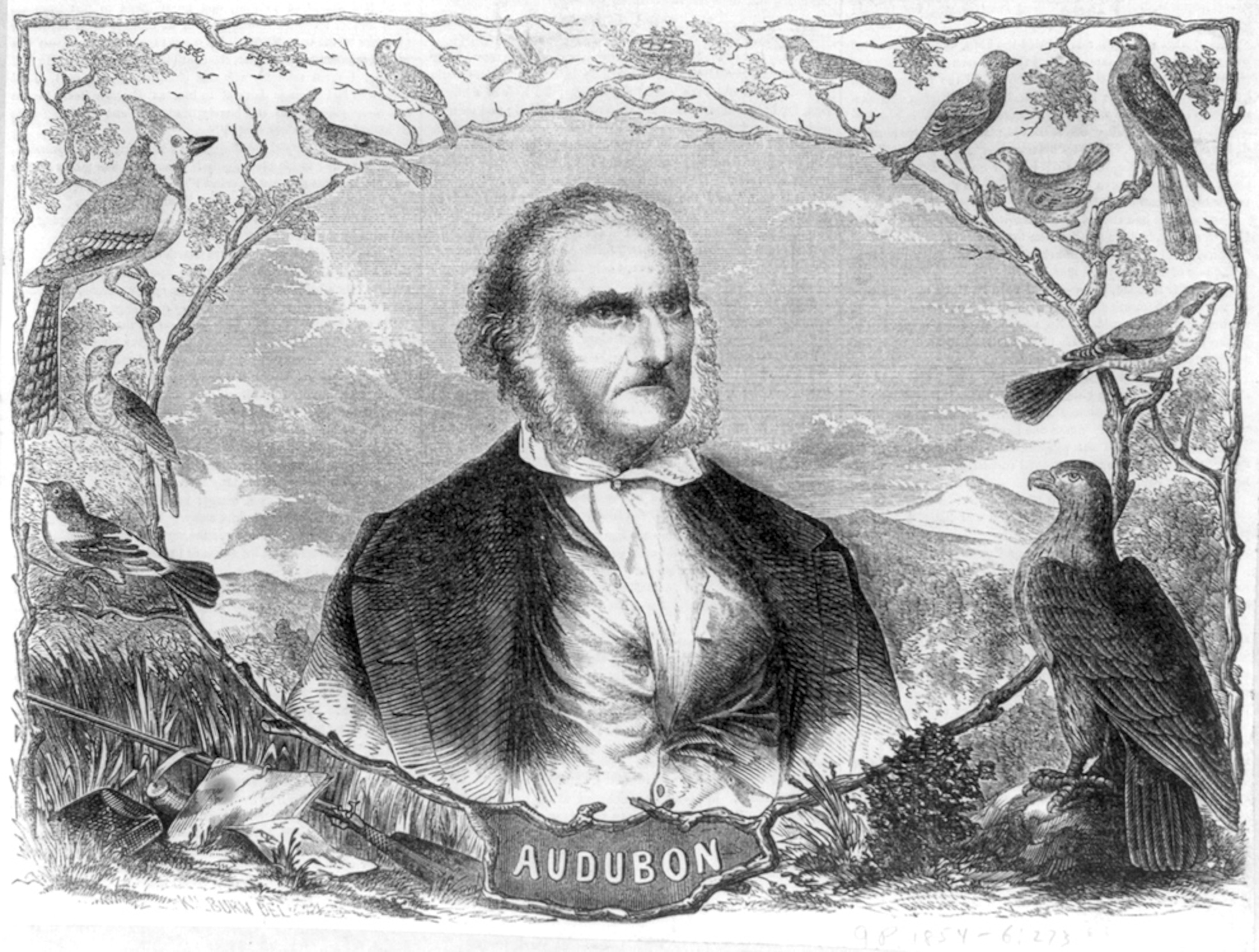

John James Audubon: Why Birds Flock Around Google's Doodle

"Cocky" naturalist changed view of birds from dinner to "intrinsically beautiful."

The Internet has gone to the birds today, with a Google doodle honoring the 226th birthday of John James Audubon, famed naturalist and painter.

Born April 26, 1785, Audubon is credited with changing the way everyday people thought about birds, thanks to his enormous tome of avian illustrations entitled The Birds of America.

"For the most part, people were looking at birds as dinner," said Jean Bochnowski, director of the John James Audubon Center in Mill Grove, Pennsylvania. Mill Grove was Audubon's first home in the United States, after he emigrated from France in 1803.

"They were looking at birds in terms of, Is this something I can potentially hunt and eat? Or, Would this bird come down and attack my chickens?"

Audubon's Masterpieces Large as Life

The Birds of America consisted of more than 400 life-size bird illustrations—including pictures of six now extinct birds—drawn by Audubon himself during his 13 years of travel around the continental United States.

(Watch video: "Citizen 'Scientists' Track Birds in BP-Spill Zone.")

Rather than being sold as a complete edition, the prints were published in batches between 1827 and 1838 and were sent out to subscribers, who paid a one-time fee of about $1,000 U.S. to have five sets of illustrations delivered to them annually.

"Generally, you would get a large print and then two mediums and two smalls," Bochnowski said. It was then up to the subscribers to bind the pages into a book if they wished.

The largest print measured about 39 by 26 inches (99 by 66 centimeters)—a size chosen by Audubon because it was the largest piece of paper commercially available at the time.

Audubon's pictures were starkly different from the birds being drawn by scientists at the time, said Robert Peck, a naturalist and historian at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

"Up to that time, most of the art that had been published about birds was quite technical and scientific. The illustrations were rather stiff and formal," said Peck, who in 2010 helped uncovered Audubon's first published bird illustration—a picture of a running grouse on a New Jersey bank note from 1824.

"By romanticizing the subject and making them works of art that people would respond to emotionally as well as scientifically, [Audubon] was able to break down the barriers between science and the popular appreciation for science."

(See "Best Rare-Bird Pictures of 2010 Named.")

Birds by Audubon Not Always Pretty

One way Audubon appealed to the masses was to depict the birds in lifelike poses in their natural habitats. His technique for doing this, however, would make most modern birders cringe.

"He would use freshly killed specimens," the Audubon Center's Bochnowski explained. "He would position it on a wire armature—a device he created—to put it in a lifelike pose. Then he would use a grid system to make sure he got the actual dimensions as close as possible."

For larger birds such as swans, Audubon would use clever tricks to fit them on the page, such as bending their necks to make it appear as if they were looking backward.

Audubon also took pains to depict each bird as naturally as possible. "He would show birds with their own families and sometimes in peril. They weren't always pretty pictures," Bochnowski said.

"At times you would see a bird attacking something or a bird being attacked by something. He didn't shy away from that." (Take a backyard birds quiz.)

It also helped that Audubon was a gifted storyteller, the Academy of Natural Sciences' Peck said. He sprinkled "personal reminiscences and anecdotes about experiencing birds in the wild" throughout Ornithological Biographies, a publication that accompanied The Birds of America.

"Previous books had very technical, clinical descriptions of birds. Audubon made them into little stories that everyone could relate to."

Audubon Book the First Birding Guide?

Historians estimate that Audubon sold only about 100 to 200 subscriptions to his massive book, but this was enough to finance his travels and keep the project going.

Audubon's book didn't become a hit with the masses until 1841, when he released an octavo edition—so-called because it was an eighth the size of the original.

For the first time, average citizens had access to art and information previously available only to scientists and the wealthy.

"In many ways, [the octavo edition] was the first birding guide, because it was the first book that was readily available to the public that not only showed birds but identified them," Bochnowski said.

(Explore National Geographic's backyard-bird identifier.)

Audubon a "Cocky" Upstart

Not everyone appreciated Audubon's style, however. He was not well regarded by the scientific community, and many scientists considered him a kind of upstart.

"He doesn't have a formal scientific education, hasn't paid his dues, and here he is, basically coming out of the wilderness in many people's opinions, and was showing art in Philadelphia, which was very scientifically oriented" at the time, Bochnowski said.

"Scientists didn't know quite what to do with him, and artists didn't know what to do with him," Bochnowski said.

Not helping matters was the fact that Audubon had an often cocky and brash personality.

"He was not shy in the ego department," Bochnowski said. "He didn't make many friends because he thought—and probably rightly so—that the quality of what he produced was better than what was produced before."

Still, Bochnwski credits Audubon's illustrations, which are highly prized today, with helping to change people's attitudes about the birds around them.

"He may not have wowed the scientific community ... but he allowed people to see these creatures as intrinsically beautiful and deserving of a place on the Earth, regardless of us," Bochnwski said. (Get bird wallpapers.)

"So when many species were threatened by [commercial] use of bird feathers and parts in the late 1800s, it was only fitting that citizens rallied around his name, ultimately forming hundreds of Audubon societies that have fought for generations to protect birds and their habitats."