The Scoop Behind Ancient Poop

Ancient reptiles that did their business together, stayed together, paleontologists report.

A giant pile of fossilized ancient reptile scat has an interesting story to tell, a paleontology team reports on Thursday, announcing the discovery of the oldest communal latrines, ones nearly 240 million years old.

These "reptile restrooms" are more than 200 million years older than previous known examples of such communal behavior in animals. And they represent the first, earliest evidence of a large animal species other than mammals exhibiting such behavior.

The use of communal latrines has only been known for some recent mammals, such as horses, tapirs, and elephants, and for some birds such as the ancient, ostrich-like Moa.

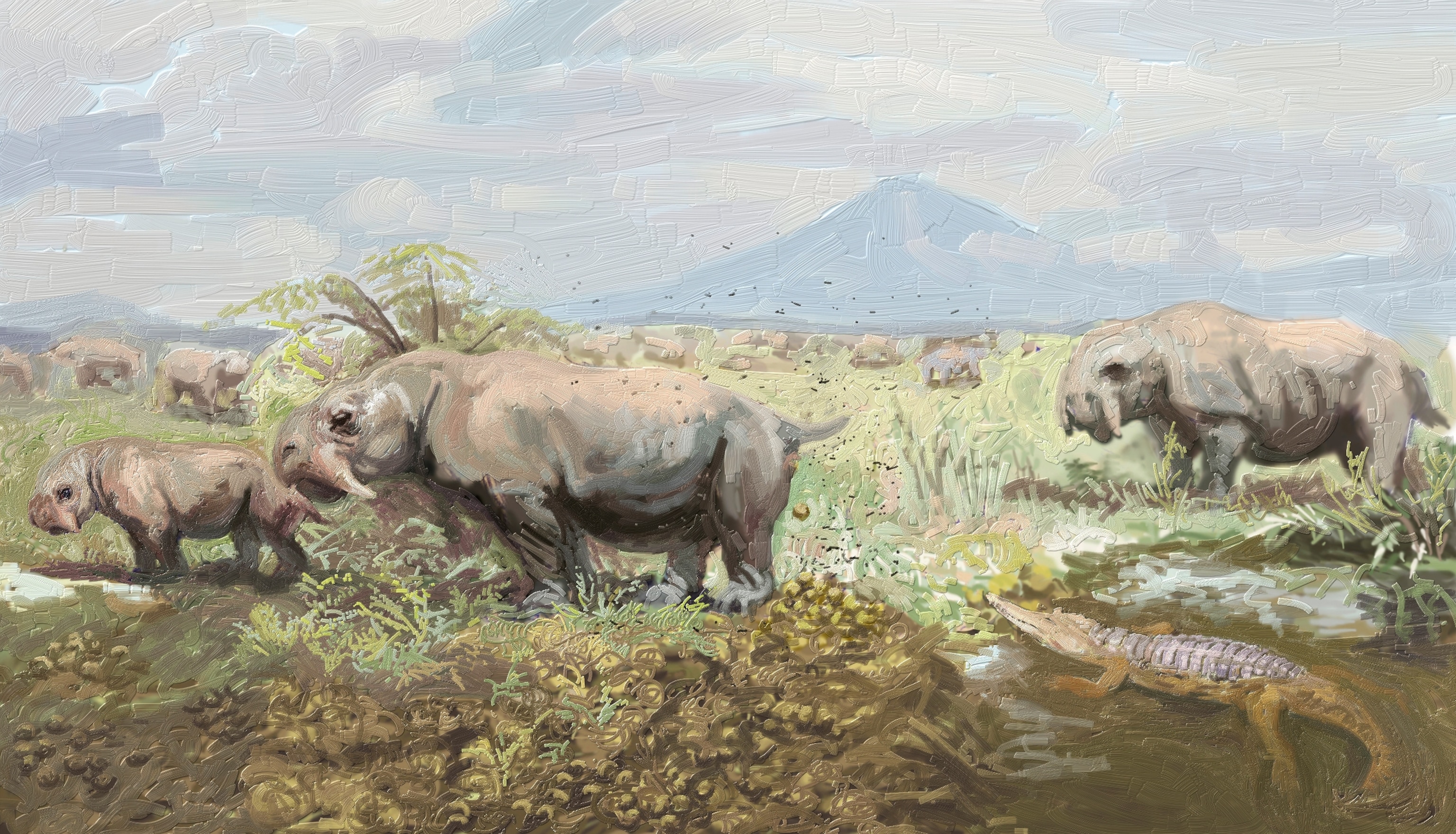

The new findings show that the complex behavior was also present in distant relatives of mammals, the rhino-like reptiles called dicynodonts, dating to a time much older than previously suspected.

(Dinosaurs' Gaseous Emissions Warmed Earth?)

"These animals exceeded weights of three tons, lived in large herds, and juveniles to adults defecated repeatedly in specific areas," said doctoral researcher Martin Ezcurra, a student in paleontology at the United Kingdom's University of Birmingham, who led the study along with Lucas Fiorelli from the Centro Regional de Investigaciones Científicas y Transferencia Tecnológica (CRILAR) research institute in Argentina.

The scientists were digging some very ancient rocks in northwestern Argentina, looking for fossils of archosauriforms, vertebrates that lived at the time of the earliest and most primitive dinosaurs, when they literally stumbled into a large (thankfully fossilized) pile of dung.

"We had two stages of discovery and surprise: first when we found thousands of fossil dung in one restricted area and second when we found seven more areas of (these) unusual fossil accumulations," said Ezcurra.

Researchers analyzed the poop using various techniques including microscopy and computerized tomography (CT) scans to reveal their inner content. Their results confirmed the plant-eating habits of these reptiles and their ancient origin.

The findings, far from being just a large pile of unpleasant fossils, tell an unexpected story about these ancient reptiles, Ezcurra says. "We were very surprised and excited that we were able to unveil such particular behavior in 240-million-years-old animals."

More Than Meets The Eye

Coprolites, as fossilized poop is known, may not be the most attractive thing to look at, but there is more to them than meets the eye.

"Coprolites don't have a very good rap, but they can provide some really unique information on how ancient organisms fed and behaved," said paleontologist Stephen Brusatte, of the United Kingdom's University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the research.

The findings serve to show the real value of ancient poop, a somewhat neglected research subject, Brusatte says. "Not many people work on coprolites, and they may seem disgusting and weird to some researchers, but they can give a lot of information."

Aside from its basic biological function, defecation fulfills several other important needs for animals, especially when done as a social affair and in a single place.

For one example, latrines help avoid reinfestations from intestinal parasites, because they are located far away from feeding sites, making dicynodonts the true authors of the saying "don’t poop where you eat."

The behavior also helps as a way of protection against predators, and to enhance communication among the members of the latrine club. But there is more, say the scientists: Ancient poop can also give us a hint on the first instances of social behavior.

Animals That Poop Together…

When it comes to animal behavior, the question of group living's first appearance remains unanswered.

The coprolites provide firm evidence that these ancient reptiles lived together and were social animals.

"I think the results are interesting. These somewhat bizarre fossils, which may get a few sniggers from people, tell us that distant mammal relatives that lived more than 200 million years ago exhibited some surprisingly mammal-like behaviors," said Brusatte.

"We didn't know much about the social behaviors, or lack thereof, in Triassic vertebrates. It's very difficult to find unequivocal indicators of social behavior in the fossil record."

Commonly, researchers look for sites with large number of footprints, or bonebeds, where multiple skeletons of the same species are found together. But these are very rare findings, as neither is preserved well over millions of years.

The new findings open a new window on social behavior, proving that coprolites can point to ancient social behavior as well as provide other useful information, such as what these animals ate at different times and ages, which gives us a hint on ancient plant diversity. That also opens the door to future research focused on understanding the evolution of flora and fauna in South America 240 million years ago.

Further details of this study can be found in the article published today in the journal Scientific Reports.