The Battle for Africa's Oldest National Park

The mystery surrounding a wounded conservationist, and the fight for war-torn Virunga

The waters of Lake Edward have finally grown calm as Josué Kambasu revs his pirogue's outboard motor, steering the craft past the local pod of hippos before heading toward the fishing boats returning with their previous night's catch.

Kambasu, the head of a local fishermen's cooperative, has invited me on an early morning tour of the lake—located within Virunga National Park in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Plagued by decades of overfishing, he tells me, Edward's stocks of tilapia, bagrid catfish, and the eel-like protopteur have begun to recover. To prove it, he’s hoping to show me pêche de Merode—local slang for a bumper catch and a testament to the park’s chief warden, Emmanuel de Merode, whose strong enforcement of fishing regulations has helped drive the industry’s revival.

Despite de Merode's popularity on the lake, it's a sensitive time to be discussing his record.

Two weeks earlier, on April 15, the 44-year-old Belgian had been ambushed while driving to Virunga's Rumangabo headquarters, shot by unknown gunmen. Although he was widely admired for upholding the law in a region long defined by lawlessness, his work also had given him many enemies: poachers, illegal charcoal harvesters, and members of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a rebel militia founded by the ethnic Hutu perpetrators of Rwanda's 1994 genocide who have long hunted the park's animals for bush meat, cut down its trees, and built bases in its vast remote areas. Along the way, they have often clashed with park rangers and raped and looted local populations.

In addition, de Merode had been a leading critic of oil exploration inside the park, currently being carried out by London-based Soco International.

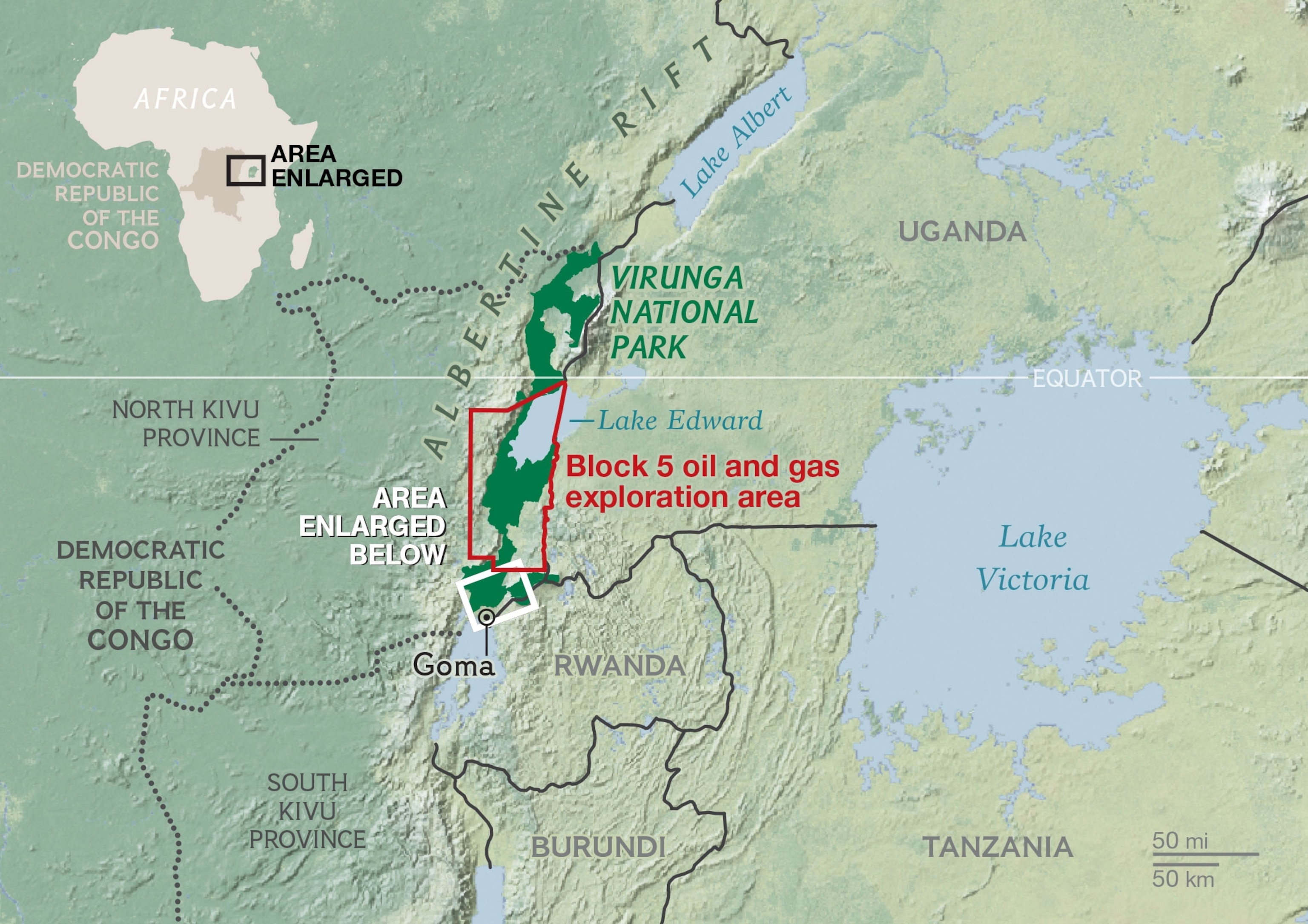

Under a contract signed with the DRC government in 2010, Soco has access to a block of land that includes 1,500 square miles of the park—roughly 50 percent—including much of Virunga's southern and central sectors and the two-thirds of Lake Edward that falls within the DRC's borders.

On May 1, as de Merode was recovering from the shooting in Nairobi, Kenya, and preparing for his eventual return to the park three weeks later, Soco contractors began recording seismic data from the lake floor. In the coming weeks, data they collect will be used to determine whether there are underground formations that might hold extractable oil.

It's a prospect, Kambasu tells me, that worries many in his home village of Vitshumbi, located at the southern end of Lake Edward. Almost entirely dependent on fishing, Vitshumbi's 20,000 residents fear a future of invasive rigs, polluted waters, and disrupted fish-spawning zones. But they also worry about potential violence, which has plagued the area for 20 years as multiple militia groups (some backed by neighboring countries) have fought the Congolese military and each other. Now the villagers see potential threats from powerful political actors vying for a piece of possible oil contracts; by armed groups targeting oil infrastructure for profit; and by local youths who, like many across the region, can't find work and often join militias out of desperation.

For now, though, there's little Vitshumbi's fishermen can do but cast their nets and hope.

The Belgian Prince

Appointed by the DRC government in August 2008, Emmanuel de Merode was an unusual choice to manage Africa's oldest national park, which is overseen by the Congolese Institute for the Conservation of Nature (ICCN), a government agency.

Born into a family of Belgian noble lineage and officially designated a prince, he first arrived in Congo in 1993 to conduct research for a Ph.D. in anthropology. Eventually he began working closely with Virunga's rangers through the Nairobi-based NGO WildlifeDirect, established in 2004 by his father-in-law, Richard Leakey, the Kenyan paleoanthropologist. De Merode slowly molded a reputation as a friend of Congo's people and its wildlife.

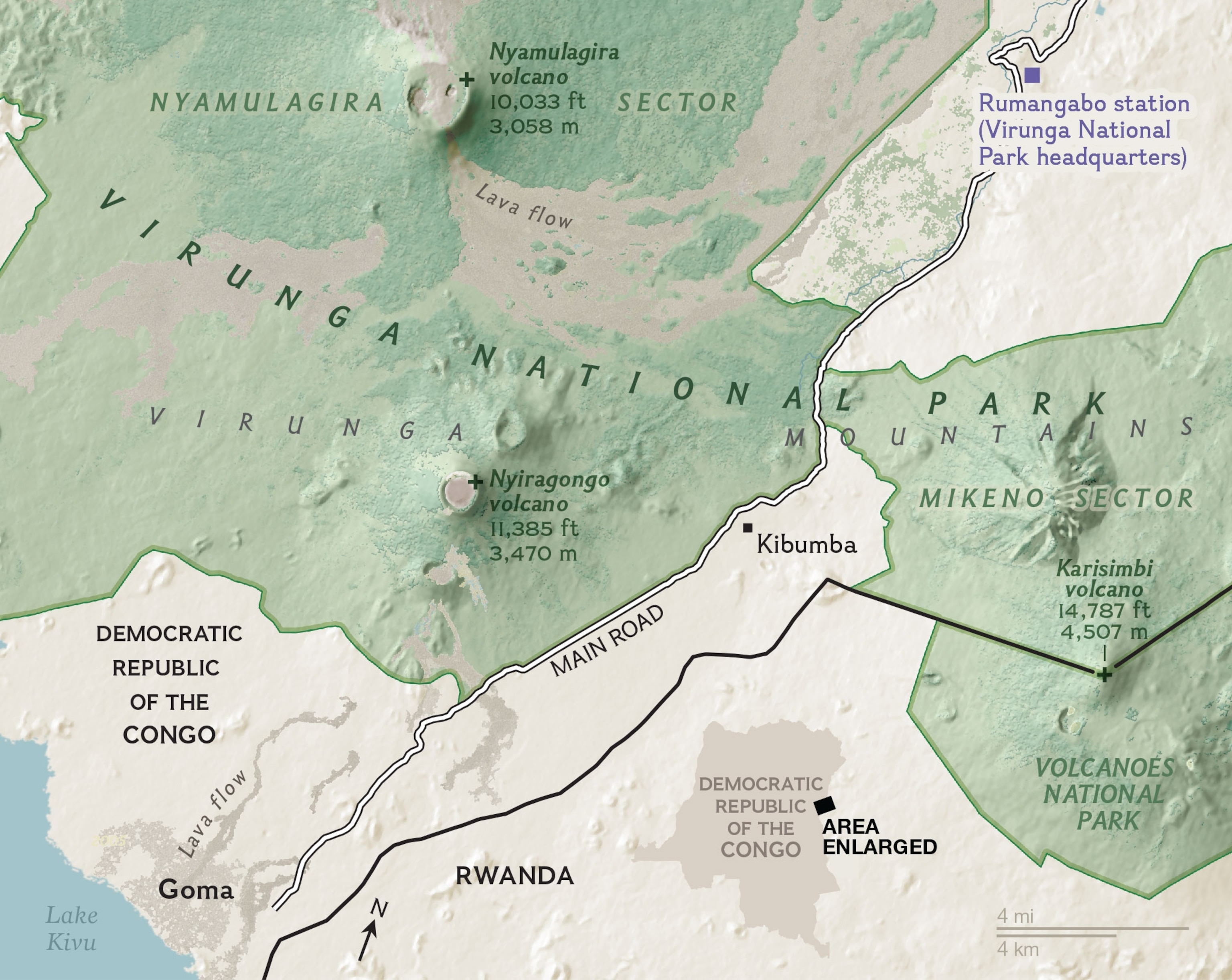

Virunga, which was founded in 1925 by Belgium's King Albert I, is a naturalist's utopia: Slightly smaller than Yellowstone, it's a land of unparalleled biodiversity, home to half of all the species on the African continent. Because of the park's wide variations in altitude and rainfall and its location along the seismically active Albertine Rift, its habitats include lava plains, tropical forests, marshes, savannas, glaciers, mountain snowfields, and two active volcanoes—including one, Nyiragongo, with what is arguably the world's most spectacular open-air lava lake.

Virunga's fauna, which includes elephants, lions, hippos, chimpanzees, and okapi—striped forest-dwelling mammals most closely related to giraffes—is just as varied. The park's most prized inhabitants, though, are 200 of the world's 880 remaining mountain gorillas, which inhabit the lower slopes of several extinct volcanoes that rise from the southeastern edge of the park and cut across the borders of Rwanda and Uganda.

Despite Virunga's natural wealth, the park de Merode inherited was a mess.

Already in decline from decades of mismanagement by previous wardens, Virunga had served for the past 14 years as a theater for what some scholars have termed Africa's World War—a multilayered conflict that, at its height, involved nine African national armies and dozens of rebel outfits, and spawned a regional humanitarian crisis that left an estimated five million dead.

Since July 1994, when more than a million Rwandan Hutu refugees—including scores who had participated in the genocide—fled across the DRC border as the Rwandan Patriotic Front captured power in Kigali, the park had been under serious strain. With the passing of time, this would only accelerate, as myriad armed groups turned to poaching, illegal fishing, and other extractive activities to fund their operations. Sometimes, as the years went on, they continued to fight because they knew no other livelihood.

By 2007 Virunga's crisis had reached a breaking point. That September, forces loyal to a Congolese Tutsi warlord, Laurent Nkunda, had captured the Mikeno Sector of the park, home of the Virunga mountain gorillas, and had refused to let any rangers inside the area.

That year, ten gorillas had been killed. As it turned out, at least seven of the rare animals were not killed by rebels or poachers, but rather by members of an illegal charcoal racket linked to the park's chief warden at the time, Honoré Mashagiro. In August 2008, with Mashagiro in jail and facing trial and the government-run ICCN reeling amid internal power struggles, Kinshasa turned to a foreigner, de Merode, to take back control of the park.

By all accounts, he attacked the assignment with gusto. First on de Merode's to-do list was to approach the rebel leader, Nkunda, and negotiate a return of his rangers to Mikeno—a feat that, despite the burning of park headquarters, he managed to accomplish by November.

Next he turned to securing the rest of the park, improving patrols of its forests, cracking down on charcoal harvesters and poachers, impounding unlicensed fishing boats, and soliciting foreign donors to boost his administration's meager budget.

De Merode also worked to improve conditions among the park's 300 rangers, whose jobs have been called the most dangerous in all of conservation. Since the start of the Congo conflict, 140 have been killed in the line of duty, yet before de Merode arrived, their salaries—which often went unpaid by the government—barely covered the basic necessities of life.

"The conditions before were very, very bad," Augustin Rwimo, a 28-year ICCN veteran, tells me when I ask how his profession has changed under de Merode's management. "But now we eat three meals a day. And everyone who is working is able to send his children to school. Most of our rangers have even built their own houses."

After boosting the morale of his staff, de Merode then turned to local people—four million of whom, he estimates, live within a day's walk of the park. Knowing that their support is crucial for Virunga's revival to be successful, he balanced his crackdown—arrests and confiscations—with new roads, schools, health clinics, and water sources. He also implemented a program to support the manufacturing of eco-friendly cooking briquettes, intended to reduce reliance on expensive and destructive charcoal.

The projects are part of an initiative known as the Virunga Alliance, an ICCN-led consortium of government, civil society, and private-sector actors working to support local residents through four pillars: promoting investment in sustainable fisheries, developing green energy, establishing agro-industries, including palm oil, soap, and papaya enzyme processing, and—as the security situation allows—working to promote tourism.

For the moment, the alliance's flagship project is a 12.6-megawatt hydroelectric plant, funded by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, under construction near the town of Rutshuru, where less than 5 percent of households are connected to the grid. Although it was delayed by yet another rebellion—the Rwanda-backed M23, which occupied swaths of the park from April 2012 until last November—the project, which follows a smaller pilot in the north of the park, is due to be on line in 2016.

"Once we have power, we believe we can create sustainable industries," says Ir Safari Samuel, an engineer overseeing the project. "Today, for many of our youth, the main occupation is war. We want to change that."

It is clear that such investments have gained de Merode the respect of many locals—from fishermen, to farmers, to children who shout his name as I pass, unaware, perhaps, that the mzungu (Swahili slang for "white person") they know best is recovering from his shooting in Nairobi.

Even so, there are some who are not happy.

In the village of Kibumba, not far from the shooting site, Cristophe Bahati, 18, tells me of neighbors who were angered last year when no one from the area was selected in a drive to recruit new rangers. In Kibirizi, several hours farther north, villagers recount an episode from last October, when they say ICCN rangers ordered the destruction of several agricultural plots, leaving local farmers on the verge of ruin. Although they admit that the fields were inside park boundaries, they say authorities gave little warning before arriving to uproot their crops and that soldiers working alongside the ICCN had threatened them when they tried to resist.

One man, Kambale Katsuva, tells me he was previously harvesting 50 sacks of potatoes a year, worth $50 each—a decent living in eastern Congo—but now is jobless. After seeking approval from the local chief, he takes me on a motorbike to show me his former field, now overrun with weeds.

"I've been farming this land for years," he tells me. "And ICCN knew about it. I don't understand why they had to surprise us like this."

The most contentious issue of all, though, is the search for Virunga's oil.

Despite Soco's contract with de Merode's employer, the Congolese government, de Merode has been a leading opponent of all oil-related activity in the park, arguing that exploration and possible future extraction not only pose grave environmental risks but also are illegal under Congolese law.

The extent to which de Merode and ICCN have been involved in legal challenges to oil exploration remains in dispute. Prior to his shooting, according to multiple local activists who track issues related to the park, de Merode visited the Office of the Prosecutor General in Goma, North Kivu’s provincial capital, to discuss a legal inquiry into the Block 5 contract. However, the prosecutor general Dieudonné Kongolo Ilunga, has said that no such meeting took place.

De Merode has not commented publicly on whether or not he met with the prosecutor about Block 5, and neither he nor ICCN legal adviser Mathieu Cingoro responded to repeated requests for comment.

Whatever the case, around 5 p.m. on April 15, de Merode was fired on by three gunmen. An hour later, he lay on an operating table in a Goma hospital, alive but deeply shaken.

A Geological Scandal

That the outside world is drawn to the natural wealth of Congo is far from a new phenomenon. Beginning in 1885, Belgium's King Leopold II embarked on a vicious campaign of forced labor and terror to extract a personal fortune from Congo's natural riches. Its rubber, ivory, diamonds, copper, and mahogany helped build industrial Belgium.

During the 32-year rule of Mobutu Sese Seko, the nation's industrial mining infrastructure withered to the point of collapse and then was largely sold off to foreign entities after 2001, when current president Joseph Kabila took office. More recently, actors linked to Rwanda and Uganda have also exploited the artisanal gold, tin, and coltan.

Overshadowed by its mineral wealth, Congo's known hydrocarbon potential has historically attracted little interest from both would-be investors and the DRC government.

Aside from limited oil production along its tiny Atlantic coast—which began in the 1960s—the country saw little hydrocarbon activity until the early 2000s, when a British firm, Heritage Oil, signed a deal with Kinshasa to explore a vast concession in the Albertine Rift, which included parts of Virunga. Although the exploration did not take place, prospecting across the Ugandan border proved successful. There, in 2006, the Anglo-Irish firm Tullow Oil made a 1.1-billion-barrel discovery in the vicinity of Lake Albert, the first commercially viable oil in East Africa. Interest in the region jumped immediately.

Soco, formed in 1991 and valued at $1.4 billion on the London Stock Exchange, is similar to Tullow, Heritage, and the many other small companies at the forefront of a new wave of oil and gas exploration in sub-Saharan Africa. Unable to compete with the industry's major players, the company focuses its search for hydrocarbons on what Roger Cagle, Soco's deputy CEO, calls "places that are not overcrowded or overpriced"—a euphemism for the less desirable and often more difficult areas of operation. It's a model, he tells me by phone from his London office, that comes with considerable risk.

"In this business, the odds are generally not in your favor," he speaks in a Western drawl, the relic of a childhood in small-town Oklahoma. "But if you're successful, the payoff can be big."

As Cagle explains, Soco's engagement in the DRC actually began in Bas-Congo, the Atlantic-bordering province in the country's distant west—where it drilled two exploratory wells in 2010 that were ultimately unsuccessful. That year, Kabila ratified a 2006 license granting a consortium of Soco and the British firm Ophir rights to Block 5, one of five government-drawn concessions in the Albertine Rift and one of three that include slices of Virunga.

Today one of these blocks remains unallocated, while the French giant Total, which heads a consortium with rights to the third, has pledged it will not explore within the park's boundaries. Yet Soco, which bought out Ophir's stake in 2012, has forged ahead, returning to Lake Edward this year after evacuating its camp during the height of the M23 rebellion.

The seismic study that began last month, Cagle says, entails the releasing of compressed air at intervals along the lake bed—a process that previously was conducted on the one-third of Lake Edward that sits in Ugandan waters. The data collected over roughly six weeks will identify whether subterranean structures exist from which oil could potentially be extracted—after which point Soco, together with the Congolese government, will assess the future viability of the project.

"The seismic study won't even tell us if there's oil," says Cagle, noting that such a discovery would require drilling—most likely on land—at a possible later phase in the contract. "It will simply give us a profile of the subsurface geology and whether there could be the potential for oil, if it is even there, to have been trapped."

The Grassroots Fight

For a leading figure in the battle against Virunga oil, environmental activist Bantu Lukambo has his office in an odd location: a gas station. I meet him in Goma, a hardscrabble town that sprawls along Lake Kivu's northern shores and, despite being briefly overrun by the M23 in 2012, is one of the safer population centers in the region.

Entering Lukambo's compound, I step past old tires, a rusted vintage fuel pump, and piles of hardened lava rocks—the building material of choice in a town that lies ten miles from an active volcano. Dressed in a purple T-shirt, carrying a cane, and limping on a clunky prosthetic leg, Lukambo invites me into his cluttered office. Speaking in French, he offers me instant coffee, served in a plastic mug, and begins to tell me how he, like Emmanuel de Merode, is working to save Virunga.

At 40, Lukambo has been fighting for Congo's wildlife for most of his adult life—a profession that has made him many enemies. The son of a local chief, he was born and raised among the fishermen of Vitshumbi, relocating to Goma in 1996, the same year the Rwanda-backed rebellion had swept through the region. Alarmed by the spike in poaching and illegal fishing as the rebels lurked inside Virunga's forests, Lukambo founded an NGO called Innovation for the Development and the Protection of the Environment (IDEP), and began partnering with ICCN and other local and international organizations working to protect the region's wildlife.

Today, Lukambo has an operational budget of $300,000, employs 22 mobile staff, and has a reputation for daring feats of activism. Since establishing IDEP, Lukambo says he's been arrested six times and been forced to flee the country twice: once after rescuing a baby gorilla that had been captured by poachers and sold to a network of animal traffickers, and again after implicating leaders of a rebel militia in the slaughter of ten hippopotamuses. His most recent brush with the law occurred in early 2012, when he organized a demonstration in Vitshumbi to protest Soco's planned exploration for oil. This, he tells me, is now the park's greatest threat.

Lukambo is not alone in this assessment.

Since Kabila ratified Soco's rights to Block 5, the firm has received a barrage of criticism from local and international conservationists, human rights groups, and even the British government. UNESCO, which listed Virunga as a World Heritage site in 1979, has said that oil exploration in Virunga violates the DRC's commitments to the World Heritage Convention and called for the cancellation of all oil permits inside the park. Over the past two months, de Merode's shooting, the start of seismic testing, and the release of a new feature-length documentary, Virunga, which includes undercover footage that purports to expose several acts of attempted bribery by individuals said to be Soco supporters and security operatives, have brought the issue back into the spotlight. Soco, which has since released a statement that insists the company "condemns all forms of corruption" and accuses the filmmakers of misrepresenting its "track record to date of responsible operating," has nonetheless been caught off guard by the outcry.

"We knew there would be opposition," Cagle tells me. "There always is. But the timbre and clamor of the people who are against this boggles my mind."

For Soco's critics, though, reasons for alarm are plenty. First there are concerns over the project's legality, under both the DRC's World Heritage Convention commitments and Congolese national law. Most critically, the DRC's law on the conservation of nature, adopted in 1969, prohibits several activities, including "disturbing or harming wildlife in any way" and "excavating, drilling, sampling, or all other work that would alter terrain or vegetation" within the country's protected areas.

As both Soco and the DRC government have stressed, however, the law contains exemptions for "scientific research activities," which under some interpretations could legally justify the current phase of exploration. In our conversation Cagle insists the current seismic survey is not against the law, and he emphasizes that Soco's only legally binding contract is its commitment to provide seismic data to the government.

Critics, like the Goma-based attorney Isaac Mumbere, disagree, arguing the loophole does not apply to any studies, however "scientific," that also have a stated commercial purpose. According to Mumbere, who also serves as a project manager at Goma's Center for Research on Environment, Democracy, and Human Rights (CREDDHO), the existing Soco contract violates not only the law of 1969 but also laws related to fishing, agriculture, and the preservation of the country's forests.

"Our position is clear that oil exploration in Virunga is against the law," he says. "We believe the contract signed by Kabila and Soco has no legal basis."

In addition to the legal debate, there are the potential risks to Virunga's vulnerable habitats—both inside the park and among the human populations at its fringes. More than two decades of studies from around the world suggest that maritime seismic surveys like the one under way on Lake Edward pose only minor risks to the health of fish, other aquatic fauna, and overall maritime environments. However, the prospect of future exploratory drilling and/or oil extraction present a host of environmental concerns—from the presence of invasive oil infrastructure to the risk of spills, leaks, and—in a conflict-prone region—disasters caused by sabotage.

After the granting of Soco's concession, Lukambo tells me, he and other activists took a study trip to Muanda, the country's only active oil-producing zone, along the DRC's distant Atlantic coast. There, he says, the locals he met were the "poorest" he has seen in Congo, noting he'd witnessed considerable environmental damage.

His findings are consistent with a 2013 investigation by CCFD-Terre Solidaire, a French NGO, which reports that more than three decades of onshore oil extraction have left Muanda's water, air, and agricultural land polluted, depleted local fish stocks, led to gas flares from poor waste treatment, and created few employment opportunities for locals. According to the report, these consequences have been exacerbated by a "context of delinquency" linked to deeply ingrained corruption and Congo's weak central state (as of 2013, the DRC trailed only Somalia in the global Fragile States Index, compiled by the Washington-based think tank Fund for Peace).

In Congo's east, still rife with insecurity, analysts warn the risks of oil activities are even more acute. According to a 2012 report by the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think tank, oil, if confirmed, would "exacerbate" the region's "deep-rooted conflict dynamics," which have long been inextricably linked to its resource abundance. In addition, the report warns of potentially destabilizing struggles for access and influence among elites throughout the exploration and production process.

According to Lukambo, this jockeying over the Block 5 contract has already begun in earnest, even if it could be years before oil in Virunga is discovered—if it's ever discovered at all.

"This question of oil, it's controlled by a small group," he tells me. "It's like a mafia. Their work is to eat this money at the expense of the population."

Lukambo continues, naming several public officials he says are widely believed to have personal financial interests in the Soco contract—even though the company may not know it—and therefore have incentives to thwart those fighting to keep Soco out of the park.

"You know," he adds, sensing what I'm about to ask him. "The place where Emmanuel was shot is one of the most secure areas around the park. There are four different army camps nearby. It's not a place where there are rebels."

Roadside Gunmen

There is little that distinguishes the shooting site from the many other forested stretches of Rutshuru Road—the largely unpaved artery that begins at Goma's outskirts and runs north through the length of the park and eventually to the town of Bunia, on the western side of Lake Albert.

Once consisting of smooth tarmac, the road, like much of Congo's aging infrastructure, gradually has been reclaimed by the elements, rendering travel by anything but four-wheel drive difficult, especially during the rainy season. Luckily, the skies are clear on the afternoon I set off from Goma with a driver and interpreter, following the route that de Merode had taken two weeks before. Skirting the base of Nyiragongo, we continue to the village of Kibumba, where teenage boys hawk beef and goat brochettes, and children play atop a rusting anti-aircraft weapon, abandoned by the defeated M23 rebellion.

A few miles up ahead, we come across a group of soldiers and stop to talk with them. I'm met by the platoon commander, who tells me he's been assigned to secure the shooting site. He invites me to have a look around. Reeking of alcohol, he slurs his words as he speaks, and I'm thankful that he's armed only with a walkie-talkie, in contrast to his four Kalashnikov-wielding subordinates. Though gruff, he's nonetheless happy to chat, telling me he didn't witness the shooting himself (his unit, he says, was dispatched here afterward), but like most, he is well versed in the details. Perhaps owing to his drunkenness, he launches into an impassioned reenactment, crouching behind a moss-covered outgrowth, which, he says, the shooters had used for cover. Unable to see de Merode's vehicle as it approached, he tells me, the would-be assassins must have had informants on the route, who kept them abreast of his whereabouts by mobile phone. Then, as the warden's Land Rover came into view, the shots rang out.

"Bam! Bam! Bam!" the commander shouts, mimicking the gun's firing. "He ended up on the ground over there," he says, pointing to a turn just down the road. "That's when we heard the news over the radio."

Who shot Emmanuel de Merode? During a week of traveling in and around the park, I find that everyone I ask seems to have a different answer. Some refuse to speculate, others pin the blame on the government, Soco, poachers, or FDLR rebels. Some ICCN rangers compare the episode with the Crucifixion of Jesus, casting the incident as a case of good versus evil. The commander tells me he thinks it was people with stakes in illegal charcoal. Before we drive off, he pulls my interpreter aside.

"Make sure this white man doesn't go back to America and tell everyone we did it," he demands. "Remember, we only came here afterward."

As is often the case in Congo, the full details of the incident may never be known. Like the country's most famous assassination plots—the murder of independence hero Patrice Lumumba, the killing of former president Laurent Kabila, Joseph Kabila's father—there will be competing theories, counterclaims, and conspiracies.

Still, some explanations are more plausible than others. As Mumbere points out, although de Merode had a long list of enemies, most of those potential threats—poachers, charcoal harvesters, rebels—had been around for years.

"He even spent a year [with the park] under the control of the M23 rebellion," Mumbere says. "The question we ask is, Why now?"

The answer to that question, both Mumbere and Lukambo believe, lies in de Merode's opposition to oil exploration in Virunga and—whatever the status of his alleged legal inquiry—his crusade against the Block 5 contract.

Mumbere and Lukambo each told me independently that they believe someone with much to lose from a suspension of the Soco contract, and much to gain if oil is discovered in Block 5, had ordered the attempted assassination.

"De Merode is someone who tried to apply the law," Lukambo says. "That was his problem."

To try to boost his theory that oil played a key role in de Merode's shooting, Lukambo shows me anonymous text messages from his cell phone, including one dated April 18, three days after de Merode was attacked.

"You see, we are determined to wipe you out if you continue to keep us from this oil," he translates the message, written in Swahili.

Another message, in French, arrived two days later. Lukambo is "playing with fire," it warns, threatening to "burn" his second leg—referencing his prosthetic. "Just because we failed to kill your director," the text says, "doesn't mean we'll fail with you."

I ask him if he's frightened.

"Oui...," he says in French, drawing out the word for emphasis. "But others are receiving the same threats too. And this is my life's work. I'm prepared to die if I have to."

The Fight Continues

Given the drama surrounding Soco, the shooting of de Merode, and the struggles of Lukambo and other activists, it's easy to forget that Virunga, by the standards of the past two decades, is actually undergoing an impressive revival.

As I travel around the park and its surrounding villages, six months after the M23's defeat, I'm struck by a sense of optimism among park rangers, Vitshumbi fishermen—even on days that pêche de Merode eludes them—and civilians who believe that a sustained peace in the region may finally be possible.

Tourists appear to be catching on, albeit slowly. Suspended during the M23 rebellion, visits to Virunga's mountain gorillas resumed in January. ICCN rangers say that treks to the summit of Nyiragongo—complete with a night at the edge of its fiery lava lake—will reopen soon. Cyprien Kinimba, manager of the luxury Mikeno Lodge, constructed in 2010 at the park's Rumangabo headquarters, says the hotel is now drawing 160 guests per month, half of them foreigners. And though Virunga is still plagued by a lack of security (during my visit FDLR rebels launched an attack on a supply truck in the park), Kinimba believes the lodge could one day become one of the most sought after retreats in Africa.

"This is not an ordinary hotel," he tells me. "We have mountain gorillas, chimpanzees... We've been given the gift of nature."

To Virunga's stewards, it's this revival, in part, that renders the search for oil so threatening. The more Virunga begins to prosper, the more it has to lose from future drilling, extraction, or—even if Soco decides to back out—the mere belief by powerful actors that somewhere underneath the park there may be oil.

Even Cagle, the Soco executive, tells me he appreciates Virunga's natural value—one reason, he says, that Soco is committed to improving the lives of the people in the communities around the park. In an alternative to de Merode's vision, he believes that oil can create jobs, which will provide alternatives to poaching, charcoal production, and other destructive activities, ultimately contributing to the protection of Virunga's wildlife. He speaks of apprenticeships and training that he says will ensure that locals benefit from the industry; of parallel charitable efforts to boost the region's quality of life. Already, he tells me, Soco has spent close to a million dollars on projects improving drinking water, supporting mobile medical clinics, and modernizing telecommunications on Lake Edward—particularly in the village of Nyakakoma, where Soco maintains a camp and where residents now have access to satellite television.

"The thing they are most juiced up about is watching the World Cup," he says.

On the ground throughout North Kivu, though, I don't find many people who are buying it. Why, after all, would locals trust a vision hatched in a faraway London boardroom, delivered by a man who, despite several trips to Kinshasa and to the province of Bas-Congo, has never even visited the communities around the park he's pledging to help?

Why should they listen to Roger Cagle when Emmanuel de Merode—a man who's spent the past 21 years working on behalf of Congo's nature and its people—has already launched a plan that's beginning to work?

One evening in Kiwanja, a town along the main road to Lake Edward, just outside the boundaries of the park, I pose this question to Irene Rugamba, 17, a high school student working as a waitress at her family's restaurant.

As she serves us a dinner of Lake Edward tilapia—grilled with onions and cassava leaves, and accompanied by fried potatoes and extra pili pili sauce—she delivers an assessment of Soco that most residents of the area would agree with.

A future of oil, she fears, will destroy Lake Edward's fish and pollute the local land and water, putting the existence of her farming community at risk.

When I counter, suggesting that oil might bring jobs and—if Cagle's words are genuine—better roads, schools, and hospitals, she pauses.

"You know," she begins slowly, speaking in English, "we are suffering for a long time because of war. But we are independent.

"To take a person who is independent and make him be dependent is not simple. Us young people, we say to Soco: No."

Jon Rosen is a freelance journalist based in Kigali, Rwanda. He reported from Goma and several locations in and around Virunga National Park. Jack Kahorha and Nelson Munganga contributed reporting from Goma.