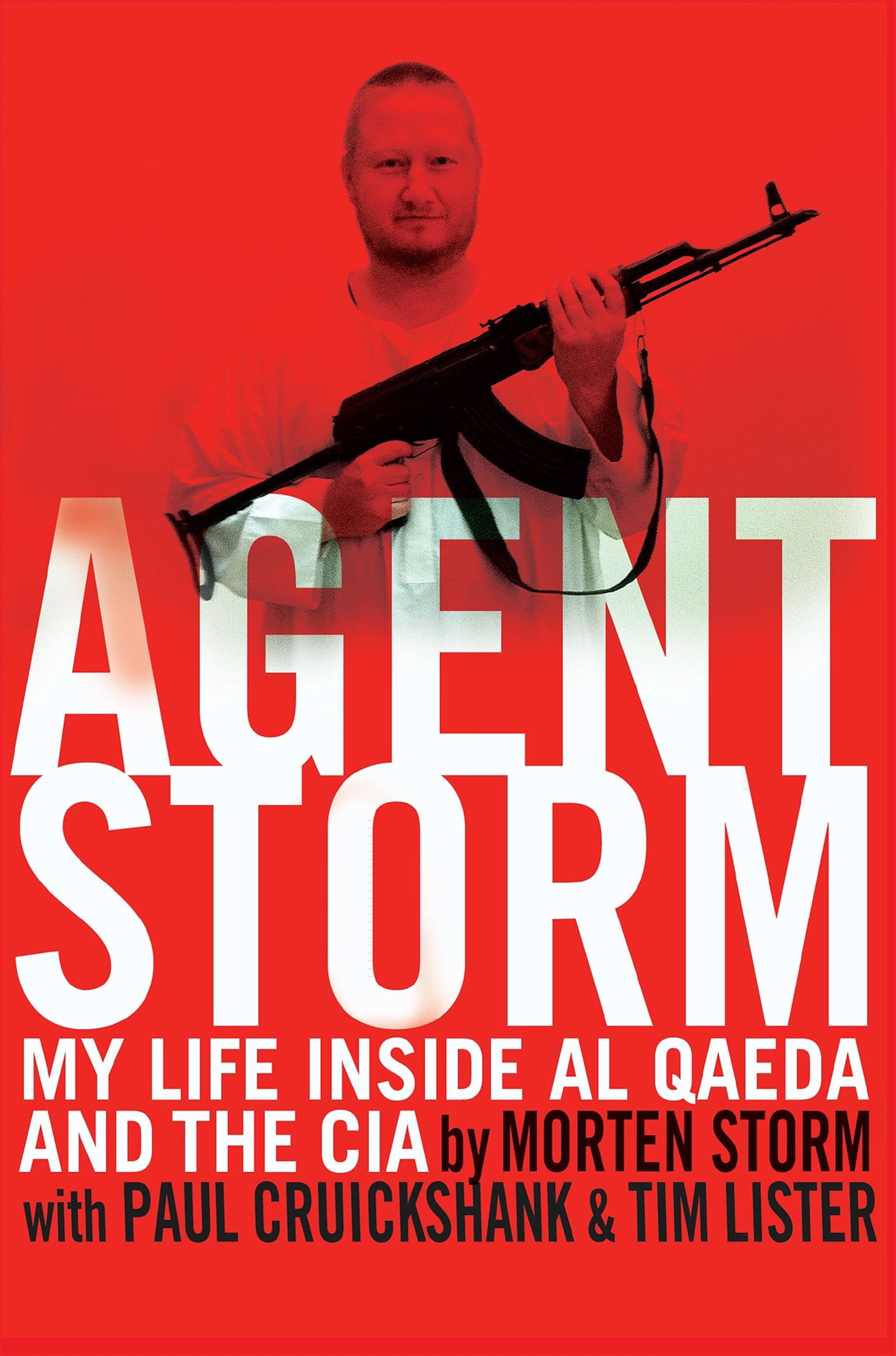

How Former Muslim Radical Helped U.S. Nab One of World's Top Terrorists

Morten Storm claims he enabled the U.S. to kill al Qaeda in Yemen's leader, Anwar al Awlaki.

Morten Storm was young, angry, and alienated when he converted to Islam. Traveling from Denmark across several continents, he came into contact with some of the most notorious jihadists, including the leader of al Qaeda in Yemen, Anwar al Awlaki.

But a crisis of faith, and an increasing abhorrence of the jihadists' violent methods, led him to a new mission: fighting radical Islam as an agent for the Danish and British secret services and for the CIA.

From an undisclosed location in Europe, he lifts the lid on fundamentalist Islam and some of his most dangerous operations—including the plot to assassinate his former mentor, Anwar al Awlaki—and explains how the West can defeat the Islamic State and other radical Islamist groups. (See also: "Iraq Crisis: 'Ancient Hatreds Turning Into Modern Realities.' ")

This is one of the most unusual interviews I have conducted, because I can't actually say where you are.

You can say I'm somewhere in the United Kingdom. That's known.

Are you under the protection of the security services?

[laughs] I'm not allowed to answer you that.

Fine. Can we go all the way back to your early life in Denmark, leading up to your conversion to Islam?

I was born in 1976 in Denmark and grew up in a small coastal town. My family was an average working-class family. At the age of eight, my father left the house for the first time. He was an alcoholic, so I didn't see much of him. My mom found a new guy, who become my stepdad. But we had a really bad relationship. I was very frustrated as a kid. I was kicked out of five schools. By the age of 13 I'd committed my first two armed robberies. I didn't have any guidance in my life, nor did I belong to anything or anyone.

Then one day I went into my local library and picked up the Koran. I don't know why I didn't pick up a Buddhist book or a book about Hinduism. But it was probably because I had a lot of Muslim friends and wanted to know about their religion. I read the whole book in the library. When I left, I was a different person.

How did you move from being a simple believer to becoming a jihadist?

When I just embraced Islam, I was a happy Muslim—if you can say so, because there aren't many of them around [laughs]. I believed that Shia and Sunni and Sufis are all the same. I knew there was a couple of groups and sects. But that was about it. I was really, really happy. I also believed that we were all the same, Muslims, Christians, and Jews. We were the people of the scriptures.

Then I went to Yemen. I studied under Sheikh Muqbil. And that's when I understood that Islam is divided into so many sects. Never mind not being allowed to like or love disbelievers. You also have to hate other Muslims! So instead of all of the love I'd embraced in Islam, I started to hate.

You were in Yemen on 9/11 with a group of jihadists. At that time you greeted the attack with enthusiasm. Does that trouble you today?

It wasn't just black and white at the beginning. It became black and white later on. When 9/11 happened, the first day, I didn't see people jumping out from the towers. When I saw it a couple days later, we were questioning if it could be permissible to kill civilians like this.

Then George Bush made a statement. He said, You are either with us or against us. Allah says those who believe fight in the name of Allah, and those who disbelieve fight for the sake of shaytan, the devil. So George Bush made it very easy for people to choose which group you want to belong to. There was no choice anymore.

You then had a crisis of faith in your life as a jihadist. Can you talk about why that happened?

We were told that Allah has preordained your destiny. If you're going to paradise or hell before you actually reach the Earth, that was something that I couldn't really comprehend. What's the point of doing good actions, if everything is already preordained?

Then, in 2006, I had an invitation to go to Somalia. One of the friends I used to hang out with in Yemen, Jehad Serwan Mostafa, was on the American Most Wanted list. He was now in Somalia. There were also other Danes and Australian nationals.

But I didn't have money, so I had to go to Denmark to work before flying to Mogadishu. I was in Copenhagen buying clothes and shoes and other stuff for my friends in Somalia, when I got a phone call from one of my contacts in Mogadishu. He said: Murad, we lost the airport. You cannot come. You'll get arrested. It's dangerous.

Allah had let me down. I threw my bag on the floor and opened my laptop. That seed of doubt I had from the beginning began to play on my mind. Why would Allah prevent me from going and fighting jihad when Allah encouraged all believers in the Koran to do it?

So I Googled dozens of websites talking about contradictions in the Koran and found to my amazement that there really were huge contradictions. And it completely wiped away my faith.

By then I'd also begun to be deeply troubled by the killing or maiming of civilians in the name of Allah. The Bali bombings, Madrid, London—these were acts of violence targeting ordinary people. If this was part of Allah's preordained plan, I wanted no part of it. But I also knew that if I told people how I felt, I could be killed for apostasy. I would lose all my friends. I had a wife and two kids.

And it was around this time that you were recruited by the Danish secret services, PET.

That's right. I decided, I'm going to fight this ideology. I will conceal my disbelief and use it to fight this ideology. So I contacted the intelligence services and offered to help fight terrorism.

You would eventually work for three different agencies: PET, MI6, and the CIA.

[Laughs] Four, actually. There was also MI5.

How would you characterize their different modi operandi and cultures?

The British were very educated and thoughtful. The Americans have a much more muscular approach. They spend a lot of money buying people's loyalty, and if you can't buy loyalty, you show them the sword. The big war machine. Whereas the British approach things more carefully. They're patient people. They gather information and win people's loyalty by promising them more long-term solutions. [Laughs derisively] The Danes were party animals. They just wanted to be part of the big table. They were also insincere. And it was because of that insincerity that I eventually went public.

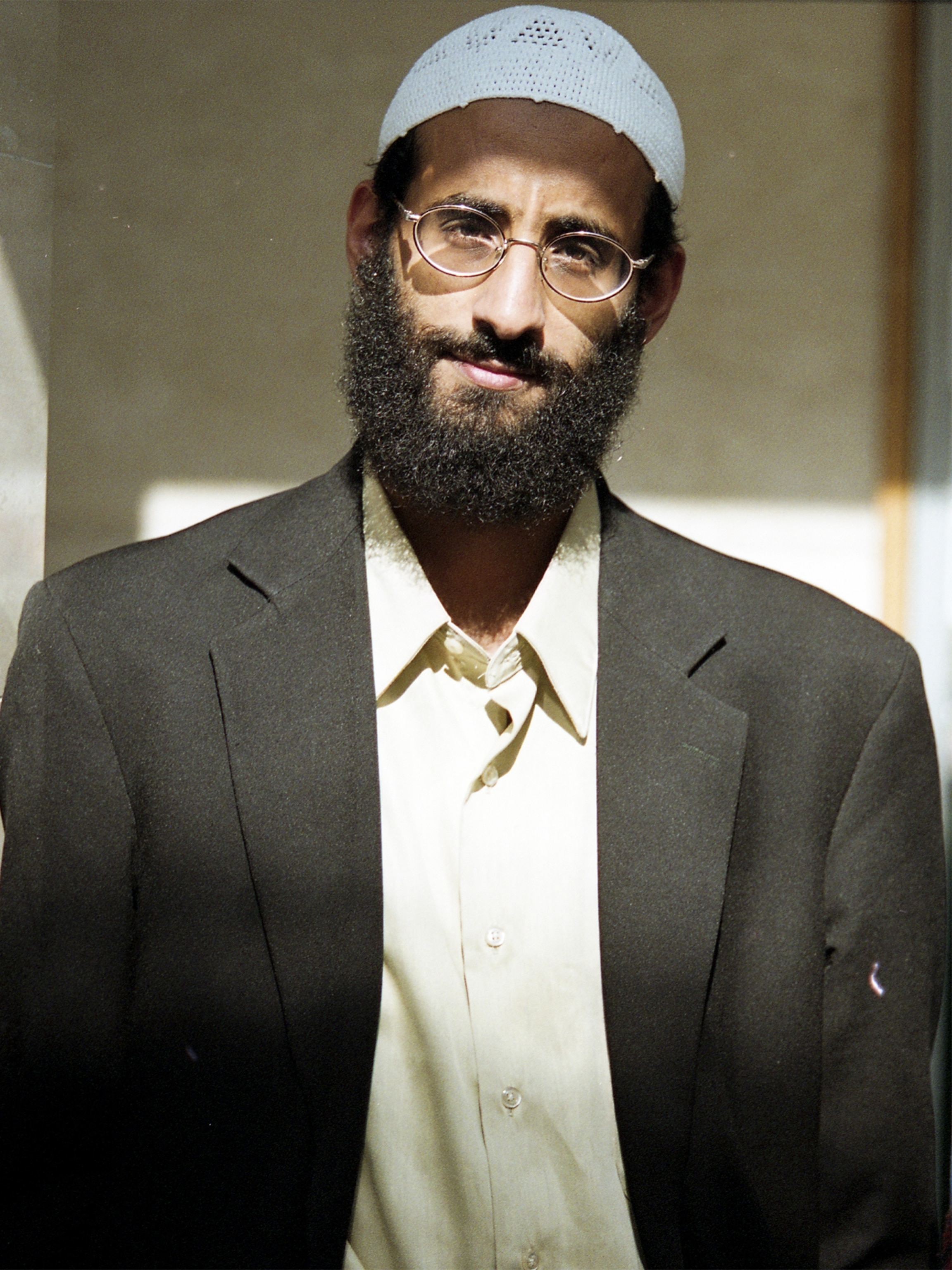

One of the main targets for the security services when you became an agent was a top al Qaeda leader, Anwar al Awlaki, whom you knew from Yemen. One of your most bizarre missions was to find Awlaki a blond wife.

That's right. I met Anwar at the beginning of 2006. He was a person who just impressed me. He had a deep inside knowledge of Islam. When he did a lecture, he referenced scholars from hundreds of years ago. It was the purest and most orthodox way of interpreting Islam. He was also very sophisticated, as he'd spent a lot of time in California. He spoke English. So his sermons were incredibly popular among young jihadists.

At our last meeting, in 2009, Anwar talked about wanting to get married to a convert from the West, preferably a blonde. I never in my wildest fantasy thought I could find any woman willing to travel to Yemen to marry him. But I knew that I had to be useful to him if I didn't want him to cut ties to me. And there is nothing more useful than a woman for people like this.

Awlaki had a Facebook fan page. I posted a message requesting support. Two days later, out of all of the hundreds of members, one contacted me. And that was Aminah [Irena Horak], a blond Croatian convert.

After the assassination of bin Laden, Awlaki became America's number one public enemy. Describe the plot to take him out.

The plan was to send Aminah over to him as a wife. The CIA said, If she crosses the borders with her passport, you have $250,000. And that happened. But she was supposed to also bring a suitcase, with a tracking device the CIA had installed. When she got to Yemen, Awlaki's people said, Don't bring a suitcase—just bring what you have in two plastic bags. She didn't even bring her passport.

The Americans were furious. And for more than six months we didn't hear anything from them. Not a word. Then six months later, when I was in Kenya, I had a phone call from Denmark saying, Big Brother wants to speak to you. The Americans had completely lost track of Awlaki. They asked if I'd help them again. They also said there would be a five-million-dollar bonus if my intelligence led to Awlaki.

So I went back to Yemen and got back in touch with Awlaki's people. He was very security conscious by now. So it all went through messengers. One day, after traveling in and out of Yemen a couple of times, Awlaki asked me if I could help him find out about what the New York Times and the West knew about his plot to extract ricin poison and make weapons of mass destruction with the minimum of resources. When he asked me that, I knew that this guy has to be taken out, no matter what.

I told Awlaki that I would gather information for him and leave it on a USB stick with a person that he and I both knew and trusted. In Yemen, I delivered the USB stick with a tracking device installed in it.

Three weeks later, I was watching the news, and the headline comes up: Anwar al Awlaki has been killed in a drone attack. Minutes later, I got a call from my handler in Danish intelligence. He said, Did you see the news? And I said, Yeah, is it true? Is he dead? Was it from us? He said, I don't know, but I'll find out. He called back later and said, Sorry, the Americans say it was not your intel.

They were scamming me out of five million dollars! And I was so furious I went to a Danish newspaper and met with a reporter named Carsten Christensen in a car park. I told him: It's me who was behind Anwar's killing. I helped the Americans to track him down. And I showed him my passport, with all my visas and travel dates.

You describe some harrowing experiences and even suggest that the CIA tried to kill you. Which were you more afraid of, retribution from the jihadists or the CIA?

I had to weigh up two evils. The lesser evil was for me to go public and choose them as my public enemies, and then protect myself against the government by having the whole Western media behind me. So if I disappear mysteriously, people now will know what happened to me. But I know I'm a wanted man for the jihadists. They showed my picture on the Web last year.

The West now faces a new threat in IS [Islamic State]. How does this organization compare with the jihadist groups you infiltrated?

They all have the same ideology, the same creed. The fundamentals are the same, the goals are the same. But the methodology, how they are carrying it out, is even more brutal than al Qaeda. [See also: "Archaeologists Train "Monuments Men" to Save Syria's Past."]

But we can defeat it—if we win the hearts and minds of people in the Middle East and also in Europe. That's number one.

On the front lines, in Syria and Iraq, we need to ensure that we don't make the same mistakes as we did in Afghanistan. If we enter a war, we should not leave before the mission has been completed. But it's going to be much harder than it was to fight al Qaeda. Or even the Second World War.

We need to have the allegiance of people on the ground. We need to train the armies. And then, obviously, our intelligence needs to be on top. And maybe, by me going public like this, the intelligence services might change the way they are interacting with and treating their agents. They should stop being selfish and start to value and appreciate their agents. And be honest.

Do you regret the path you took in life?

I don't. I'm very privileged to know that I have contributed to something good. I've made a difference—put my footprint down on this Earth, and I'm really proud of it. And I really, really hope that my insights can continue to help, educating people about this jihadist ideology and the threats we face today.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.