Conservationists Spar With Fishermen Over World’s Largest Marine Monument

Federal officials weigh arguments on President Obama’s proposal to expand the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

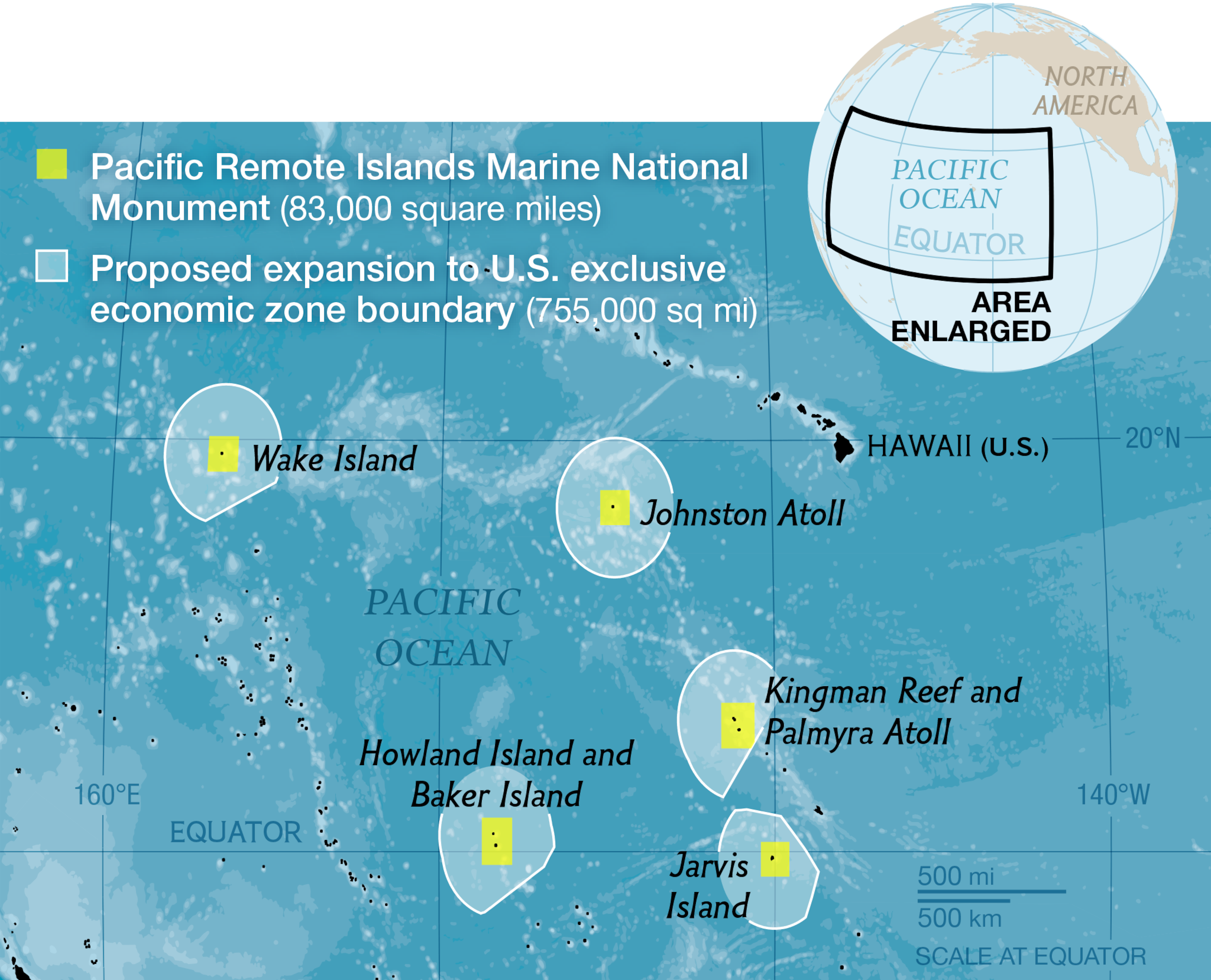

President Obama’s proposal in June to expand a marine sanctuary around seven U.S.-controlled islands and atolls in the central Pacific Ocean drew immediate praise from scientists and conservationists, but has since sparked opposition from representatives of the tuna industry, including fishermen in Hawaii who say it would threaten their livelihood.

The tuna fishermen oppose the plan because commercial fishing is prohibited in the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, which would increase from nearly 83,000 square miles to nearly 755,000 square miles (215,000 square kilometers to nearly 2 million square kilometers) under the plan Obama announced.

“No other country is restricting fishing in its own waters to this extent,” says Kitty Simonds, executive director of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, which manages fisheries in the Pacific.

But conservationists argue that the proposed expansion would have minimal impact on the industry, saying fishermen haul little tuna from those areas.

“Even if those places are made off-limits, the fishermen won't lose that percent of their catch because they will be able to fish in other areas,” says Jack Kittinger, the director of Conservation International’s Hawaii office.

Although the public comment period ended August 15, Obama administration officials have met over the past few weeks with conservationists and fishing representatives to work out the details of what would be the world’s largest protected natural area. A final ruling could come any day, although administration officials declined to discuss their decision process.

President George W. Bush first designated the monument in February 2009, protecting an area that extended out to 50 nautical miles around seven uninhabited islands and atolls: Kingman Reef and Palmyra Atoll in the northern Line Islands, Wake Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Howland Island, and Baker Island.

On June 17, Obama proposed extending the monument to include the entire 200-nautical-mile U.S. exclusive economic zone around those areas.

"I'm using my authority as president to protect some of our nation's most pristine marine monuments, just like we do on land," Obama had said at the time.

National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Enric Sala led a National Geographic science expedition to the region in 2005, which documented rich biodiversity and reefs in a largely pristine state. He says the proposed monument would protect deep corals that are thousands of years old, 22 species of marine mammals, five species of endangered sea turtles, and millions of fish and nesting seabirds. The area hosts one of the largest populations of manta rays and sharks that Sala has seen anywhere, including endangered silky and oceanic whitetip sharks. One of the islands, Kingman Reef, was featured in the July 2008 issue of National Geographic magazine.

The discoveries were cited by Bush in his presidential proclamation that created the monument. Bush, like Obama, used his power under the 1906 Antiquities Act to protect the area.

More than 135,000 U.S. citizens have sent letters of support for the proposed expansion, as have more than one million people from around the world, according to environmental organizations that tracked the submissions. More than 200 scientists who have worked in the region signed a letter of support, as have more than 40 national environmental groups and foundations, 30 Hawaii-based nonprofits, and 35 Hawaii-based businesses, including water sports outfitters.

In a September 12 letter to Obama, Maui County Mayor Alan Arakawa, who lived on Wake Island for two years as a child, wrote that as a diver, he has been distressed by the “severe decline in the coral reef habitats in Maui County and throughout Hawaii.” To ensure “the survival and abundance of many species that may be threatened elsewhere,” he added, it is “vitally important that we extend protection of these locales that have been minimally impacted by human presence.”

The Obama administration declined to release information about the comments filed in response to the proposal, making it impossible to tell how much support opponents were able to generate during the comment period.

But American Samoa’s representative to Congress, Eni Faleomavaega, wrote a letter to the president in July opposing the expansion, saying it would have little impact on marine conservation and “prove an economic hardship for area fishermen.”

Opposition From a Fishing Group

The Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, based in Hawaii, had opposed the creation of the monument in 2009. At a boisterous town hall meeting in Honolulu in August and in a meeting at the White House on September 9, representatives of the council made their case against expansion, arguing that current fisheries laws adequately protect marine wildlife.

Simonds says the Hawaii-based longline fleet, which fishes for tuna and other large predatory fish, in 2000 set about 16 percent of its hooks in the area of the proposed monument expansion, marking the high point for fishing there.

That fishery is already a “global model” of sustainability, she says, although she notes that it could be improved. She’d like to see purse seine fishermen switched from vessel day-limits to a catch quota system, which currently governs longline fishermen and is a better way to control overfishing, she says.

But Conservation International’s Kittinger says data from the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (which oversees international fishery agreements in the area) shows that, since 2008, less than four percent of the U.S. Pacific tuna catch came from within national waters, with just a fraction of that from within the proposed monument.

Simonds and her colleagues dispute that assessment. Sean Martin, who owns six commercial fishing boats and serves as president of the Hawaii Longline Association, says he and his colleagues frequently travel to the monument area, even though it is about 900 miles (1,450 kilometers) from Hawaii to the nearest of the seven islands.

Paul Dalzell, a senior scientist with the Western Pacific council, said, “Fishermen go where the fish are. Right now they’re in the eastern Pacific.” But he noted that they often move with the ocean’s periodic temperature shifts.

During El Niño years fish tend to migrate toward the proposed monument expansion area, and the frequency of El Niños is expected to double due to climate change, says Dalzell.

Kittinger counters that, even during El Niño years, only 10 percent of the Pacific fleet’s total catch comes from that region. But Dalzell says during the 1997 El Niño, 21 percent of the catch of Hawaii-based purse seine fishermen was taken from the monument area.

Martin, who has worked as a fisherman for about 40 years, told National Geographic that the Hawaii-based fleet is getting squeezed by increasing limits on the high seas and in the waters of other countries, as well as substantially higher usage fees to fish within the waters of other countries.

Martin notes that, while the expanded monument might not have a major impact on the overall Pacific fleet, it would hurt Hawaii’s fishermen. The Hawaii-based fleet includes 145 active longline vessels and about 40 purse seine vessels, Martin says. “We're going to lose something,” he says.

Kittinger believes the fishing community is most concerned about the precedent the new monument would set. “But there's a high benefit-to-cost ratio here; we stand to gain a lot and lose very little to the fishing industry,” he says.

Important to American Samoa?

The fishing council and Congressman Faleomavaega argue that restricting fishing around the Pacific islands will damage the economy of American Samoa, a U.S. territory with a per capita income of only $8,000.

Claire T. Poumele, the director of American Samoa’s port authority, told National Geographic that the island’s two tuna canneries provide about 5,000 jobs, roughly a third of the workforce. The U.S. purse seine fleet delivers about $60 million in tuna annually to those canneries.

“It is very likely that the canneries would go away if the proposed monument expands,” says Eric Kingman, a fisheries enforcement official with the Western Pacific council, adding that “they are getting squeezed” by increasing regulations and competition from Asia.

However, according to media reports, the majority of the fish processed at the canneries has come not from U.S. waters, but from waters off Papua New Guinea and Micronesia.

A representative at StarKist, a cannery owner, seemed not to be aware of the proposed monument expansion when reached by National Geographic. The company later responded with a statement, saying, "We feel that it is wrong to put American industry at risk given the lack of scientific evidence to back the move."

Heidi Happonen, a spokesperson for Tri Marine, another cannery owner, says only 4.75 percent of the fish caught by the company’s own fleet of 10 American Samoa-based vessels came from U.S. territorial waters between June 15, 2013, and September 12, 2014. Happonen says, “The proposed monument expansion alone would not deter Tri Marine from our vision in American Samoa,” which includes $70 million spent to refurbish a tuna cannery that would employ an expected 1,500 people.

Happonen says the monument would still “likely negatively affect the local fleet and raw-material supply from local vessels, and therefore fishing and fish- processing livelihoods.”

She adds that Tri Marine is concerned about the monument expansion in light of negotiations over the extension of an international treaty that governs purse seine fishing for tuna in the region. The current agreement expires in December; a new treaty could include more restrictions.

“My sense is that the fear coming out of American Samoa is due to the timing, the double whammy of the proposed monument expansion and pending treaty negotiations,” says Happonen.

Martin, the Hawaii fisherman, criticizes much of the science the Obama administration has pointed to in justifying the monument as having been done by “environmental advocates” like Conservation International, Pew Charitable Trusts, and National Geographic. He says the area is “already pristine” and past closures of parts of the Pacific high seas in 2010 and 2011 did not increase stocks of tuna.

The Western Pacific council argues that bigeye tuna, its primary target species, is being managed sustainably, but Pew points out that, worldwide, 90 percent of all large predatory fish like tuna have been removed from the ocean.

Although the council says existing purse seine nets only go to a maximum depth of 200 meters (650 feet), and so are above many seamounts that host fragile corals in the monument, Pew argues that without permanent protection, there is no guarantee that future fishing gear won’t cause harm.

The industry says seabirds are already protected by the existing monument, but conservationists say new evidence shows they are frequently in the expanded area. Longline fishing has been implicated in the decline of seabirds worldwide.

Monica Medina, the senior director of International Ocean Policy for National Geographic, says the debate over whether to expand the monument really should not hinge on a cost-and-benefit analysis to fisheries.

According to the Antiquities Act, “it is really a question for scientists, historians, or archaeologists to see whether something is that unique and deserves protection for future generations,” says Medina, who argued the case for expanding the monument in a meeting at the White House. “That's the calculus.”