Island Hopping: A Former Journalist Sets Off to Uncover the True Indonesia

What I love most about Indonesia is the extraordinary generosity of spirit of the people, author says.

For 13 months former Reuters journalist Elizabeth Pisani trekked 13,000 miles (20,900 kilometers) across Indonesia by motorbike, bus, and boat, sleeping on mats in mosquito-infested bamboo huts, meeting and talking with ordinary Indonesians. The result, Indonesia Etc., is a sweeping panorama of a vast country of diverse peoples and cultures.

From her home in London, Pisani talks about why Indonesia is like a bad boyfriend, the meaning of "sticky culture," and the complex challenges that face Joko Widodo, who next week will be sworn in as the seventh president of the Republic of Indonesia.

The title of your book—Indonesia Etc.—sounds somewhat random. Why did you call it that?

"Indonesia etc." is a phrase taken directly from the Indonesian declaration of independence, which reads, in its entirety: "We, the people of Indonesia, hereby declare the independence of Indonesia. Matters relating to the transfer of power, etc., will be executed carefully and as soon as possible."

For me that sums up the spirit of the country. "OK, we're going to give this a try, and maybe we'll have to do some trial and error. But one way or another, we'll make it work." And that's exactly what's happened.

You describe Indonesia as being like "the bad boyfriend." Explain.

You know how it is with bad boyfriends or bad girlfriends. They make you feel all warm and fuzzy inside; you have all these shared intimacies. But then they tell these endless low-grade lies, they steal from your friends, and you know it's all going to end in tears.

But for some reason you keep going back for more. In a way that is my relationship with Indonesia. It's one of the most fascinating places on the face of the Earth—and incredibly rich, which is always nice in a bad boyfriend. But it's also immensely frustrating and maddening, because it never quite seems to reach its full potential. Or make the world aware of how glorious it is.

You also call it "the improbable nation." Why?

Think about it. It stretches the equivalent distance from London to Tehran. It comprises 13,500 islands at high tide, of which 7,000 are inhabited. There are 360 ethnic groups, 700 languages, and really massive cultural differences—different religions, different belief systems. So it really is amazing that it came to be cobbled together into a single a nation. And yet it works.

Cave paintings in Sulawesi were recently dated to nearly 40,000 years ago, making them as old as the famous cave paintings at Le Chauvet in France. How did you react to that news? And what does it say about Indonesia?

To be honest, when I heard the news about the cave paintings, I slightly rolled my eyes. Gosh, isn't it typical that Indonesia has this wonderful treasure, and it's only just coming to the world's attention! But I think that is very typical. There are so many glories and treasures that are still buried in Indonesia that haven't yet come to international attention.

You led two Indonesian lives. One as a journalist. Then you returned as an epidemiologist, specializing in HIV. How did you combine these two very different professions?

People always ask me how I went from being a journalist to an epidemiologist. But they're really not that different. The skill set is basically the same: Find the right people, ask the right questions, organize the information, analyze it coherently, and then communicate it to someone who can do something about it.

One of the core principles of epidemiology is random selection. And Indonesia is so vast and so full of the unexpected that I knew that I'd never be able to encompass all of it. But in epidemiology, instead of saying we're going to talk to everyone to get the best picture of what is going on in this civilization, you use a random sample.

And I used that principle for writing the book. I got on a boat. I didn't have a plan for where I was going to go or what I was going to write or the kind of the people I was going to speak to. I would just try and speak with as many people in as many places as I could. It's by no means a comprehensive portrait of Indonesia. But it's certainly varied, because I just allowed myself to be open to everything that came along. And what comes along in Indonesia is always fascinating and astonishing.

You spent time with some wonderful characters during your travels. Tell us about Mama Bobo.

Mama Bobo is a matriarch of a clan in West Sumba. She belongs to the Loli ethnic group, a culture that is based very much around feasting and sacrifice. And the feasting and sacrifice takes place particularly once people are dead. The sacrifices will be of pigs and dogs and buffalo and chickens.

But sacrifice is an expensive business—slaughtering a buffalo will set you back $2,000. And at someone's funeral, dozens of animals are slaughtered. Because no one has that much cash at hand, the way families cope is this loan system: I bring a buffalo to your grandmother's funeral, then you have to bring a buffalo to my family's funeral.

Mama Bobo invited me to her sister-in-law's funeral, the second of her brother's four wives. She was much younger, and she was deeply unpopular with the other three wives. The first one died a couple of years earlier, and the second one died when I was there. Mama Bobo brought this massive buffalo to the funeral. And I thought, What's going on here? You don't get on with your brother, you hate the youngest wife, and yet you're giving her this great gift.

Then I realized she was storing up trouble for her because the hated sister-in-law is now in debt to the tune of one magnificent buffalo, which she has to replace anytime Mama Bobo snaps her fingers.

The concept of clan [keluarga besar] is the bedrock of Indonesian society. How does this benefit—and deform—social relations?

That's a very interesting question. Indonesians are very well embedded in their societies. There's much less alienation or dislocation than in Western countries and other, more industrialized Asian countries, like Japan. I think that's because of the strength of the clan. You always know where you stand. This gives you a sense of security and a sense of confidence.

However, the sense of security doesn't necessary go very well with an active striving for advancement. Indonesia is a very rich country. It's very fertile. It's not that hard to survive. And when you know that you have the backing of your clan, you don't necessary need to be terribly motivated to go out and make your way in the world.

The other thing that's interesting about the idea of clan, and the social obligations it brings, is that it creates a culture where patronage flourishes. And when that is translated into a political context, there's a very fine line between patronage and corruption.

You use a wonderful phrase—"sticky culture"—to describe the local traditions on the island of West Sumba. Tell us about adat and how it continues to shape life in modern Indonesia.

Adat is an incredibly complex concept. It's very often translated as tradition. But it's much more than tradition. In many places it has a religious dimension. It has a legal dimension. It's the way societies organize themselves, but also the way they express their identities.

Adat is a way of holding on to your roots and justifying the difference between you and other people. It also used to be a very good way of resolving disputes. If you steal a buffalo, instead of the matter being taken to the police, it's taken to your adat leader, who says, In accordance with our traditions, you owe this person 20 cows.

But one of the interesting things about Indonesia now is that there is much greater mobility, so you now have different communities sharing the same space. That means you can't really use that adat system anymore to resolve disputes. And that's worrying, because the legal system is very weak.

In the acknowledgments you credit your parents with teaching you to travel fearlessly and freely. Tell us a bit of your own story.

My parents met when my father was hitchhiking around the world and my mother was hitchhiking around Europe. They met in an immigration queue in Ostend [Belgium], of all places. So I guess travel is in my blood.

My father's American, my mother's British. I was born in the Midwest, in Ohio—a Procter & Gamble baby. My parents were always great travelers. We moved to Germany and western Europe. I lived in France, Germany, Spain, and the U.K. as a kid. When I was 15, I visited a school friend who was living in Hong Kong, and I was absolutely captivated by Asia. I went on and studied classical Chinese at university. And I never really looked back.

You constantly had to tell lies about yourself as you traveled, including even that you were a nun. Why the subterfuges?

[Laughs uproariously.] I never actually told anyone I was a nun—they just assumed I was a nun! I was traveling in places where there was no accommodation, I was sitting on a cargo ship for four hours, and I essentially was at the mercy of my fellow travelers. So I had to make myself as likable as possible and not too scary. And the reality of me—which is unmarried, actually divorced, no kids, no job, no religion—would have made me too weird, too scary for people to invite me to their village or homes.

There are three things that Indonesians find completely baffling. One is atheism. Another is traveling alone. People find it almost upsetting. "Don't you have any friends?" they would say. [Laughs.] The third thing is being childless. People interrogate your ovaries all day long. [Laughs.] They say, "You must meet my uncle—he's got a special potion! Three women in the village got pregnant. Old ladies like you!"

Or they would say, "How many kids does your husband have with his younger wife?" It got a bit wearing after a while. So I just fitted in as best I could, sometimes by just making things up—like a husband who was always waiting patiently for me at some nearby town. I went back to the religion of my birth, Catholicism.

I resisted having children for a long time. Then one day I was sitting in a café, and these young guys asked me how many kids I had. "Two," I said. It just popped out of my mouth. And I thought, God, I should have made up kids months ago!

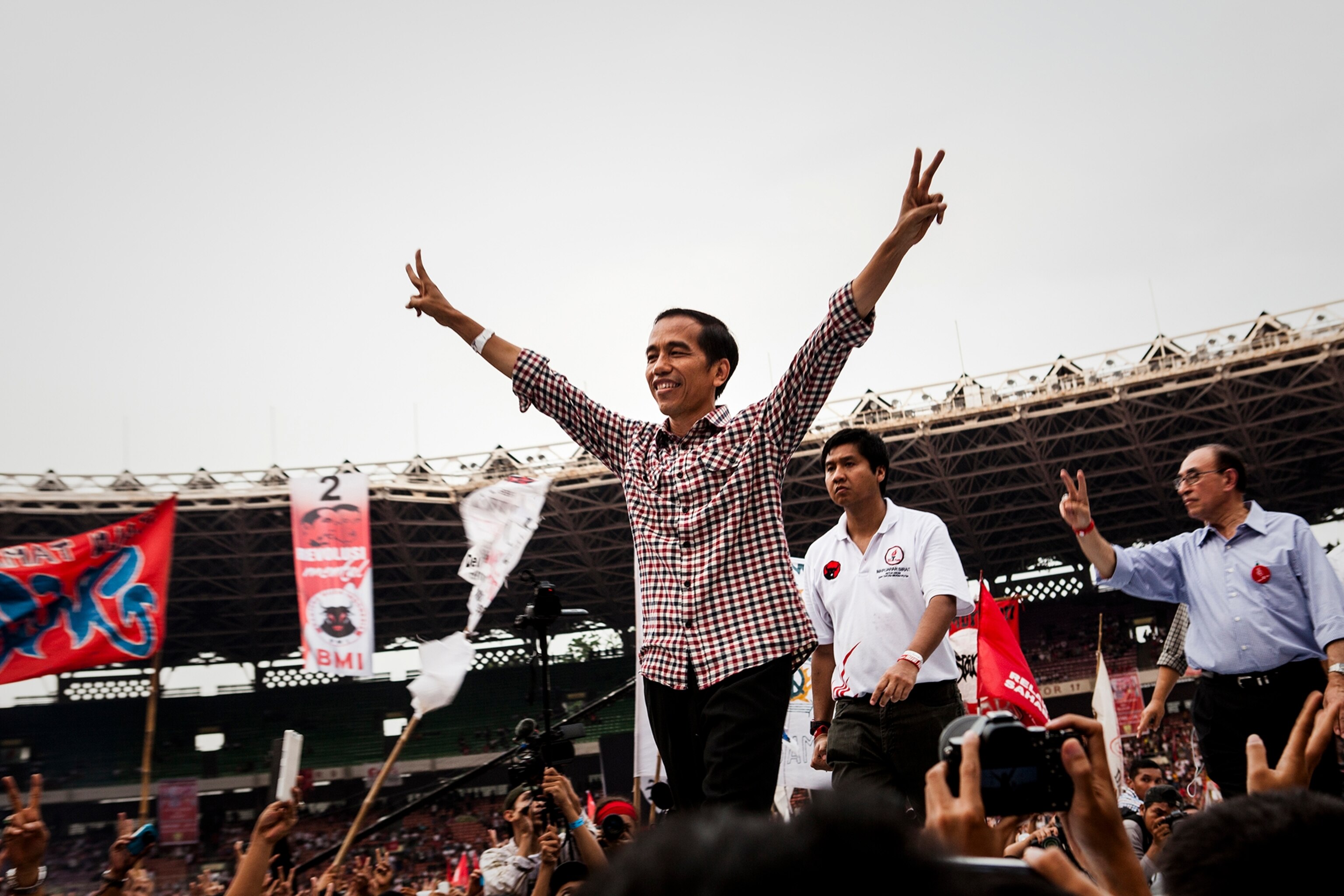

Incoming President Joko Widodo has been compared to Barack Obama. Tell us why he's a break with the past and what you think are the biggest challenges he faces.

Phew! That's a big one. [Laughs.] Joko Widodo, or Jokowi, as he's universally known by his nickname, is a break with the past because he's the first national political figure to come up through the decentralized political system. His mandate comes directly from the people, not the political parties or a particular oligarch or faction.

He has come up through his own hard work delivering services to people, first of all in a small city on Java called Solo, where he was reelected for a second term with an astounding 97 percent of the vote. He became governor of Jakarta and then ran in the presidential elections against someone who absolutely represented the old guard, Prabowo Subianto, a son-in-law of Suharto and a general in the armed forces with a bit of a dodgy human rights record. Jokowi won out in the popular vote—on the basis of a record of curbing the bureaucracy, introducing meritocracy, and actually delivering services to people. And that's pretty much unheard of in Indonesia.

The parallel with Obama is tragically rather an apt one. He's a popular reformist leader whom people have high hopes of. But he's beholden to a parliament that is controlled by the old guard and the people he beat in the election. They've already tried to make the country less governable, so when Jokowi takes office next week, he's going to be holding something of a poisoned chalice.

Number one on the list of things to tackle is, without a shadow of a doubt, infrastructure. But he can't tackle the infrastructure problem until he tackles the financial problem. Indonesia has an incredibly expensive and inefficient fuel-subsidy program. But no one has had the political courage to get rid of it, even though most Indonesians think it's pretty ridiculous. So he'll have to create the fiscal space to invest in infrastructure by getting rid of energy subsidies. But it will be quite difficult to do.

Maddening though you find Indonesia, your book is ultimately a love letter to the country. What do you love about it?

I love the randomness and the chaos and the fact that adventure just comes to you. Most of all I love the extraordinary generosity of spirit of the Indonesian people. And I think there's a geographical and historical reason for that.

The concept of Indonesia is a very new and not very well entrenched one. It's a collection of islands, and people have traveled and traded through those islands for millennia. Even people on the next island were strangers, and that meant that everyone was used to interacting with strangers—and indeed had an interest in doing so, because those strangers might be bringing something you wanted to buy or might want to snap up something you're trying to sell. I think that has left Indonesians with legacies of openness, curiosity, and instinctive hospitality, which are very attractive features.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.