Arctic Ship Breaks Free of Ice for Historic Expedition

A Norwegian research vessel will spend six months on the sea ice to study the changing Arctic.

Editor's Note: This is the second dispatch from aboard the R.V. Lance, an Arctic research vessel.

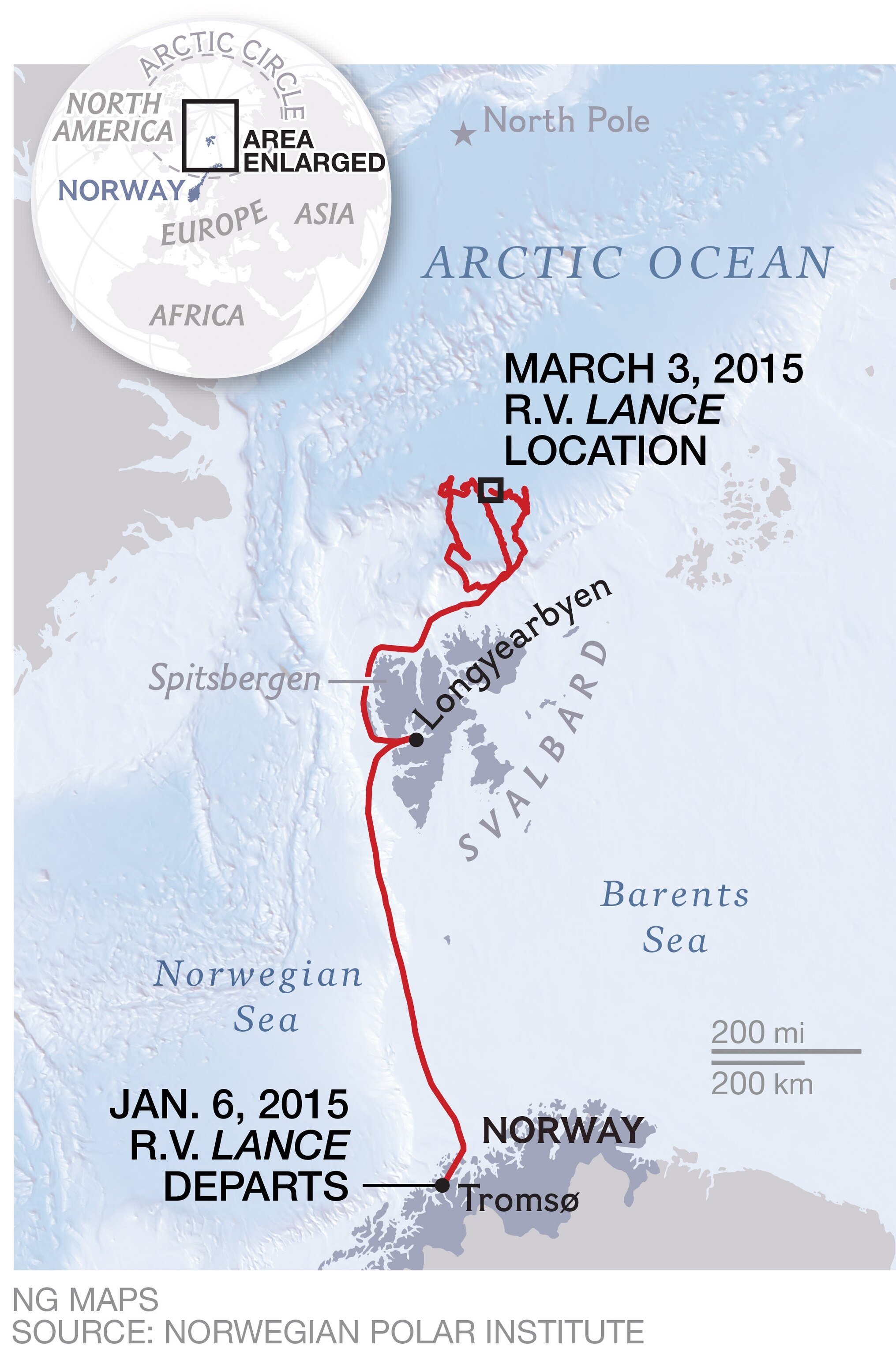

82.58 Degrees North—The Norwegian research vessel Lance is back where it wants to be: adrift in the Arctic, moored to a large ice floe.

After the ship spent five weeks locked in sea ice, high winds had pushed it to the crackled edge of the ice pack. For three days and nights, a Norwegian Coast Guard ship led the Lance back into the ice, using satellite data to pick a path through a labyrinth of navigable fractures, called leads, which penetrate the frozen sea. (Read the first dispatch in this series.)

Then finally on the morning of February 24, our Coast Guard escort abruptly turned toward civilization, and toward a pinkish glow on the southern horizon. It left us and the Lance marooned at the 83rd parallel, just west of Russian territory and 483 miles (777 kilometer) from the North Pole as the petrel flies.

The Lance shut off its main engine, and the scientists on board got to work.

Peering out across a frozen white surface stretching to the horizon in all directions, it's virtually impossible to tell that the Arctic is in a state of alarming change. In September 2012, sea-ice extent in the Arctic reached a record low. The floes of drifting ice are also now substantially thinner, younger, and faster moving overall than those observed in the early 1990s. That's why the Lance is here to investigate.

"There have been few studies of the Arctic in the winter, and none in this new type of situation in the Arctic Basin," explains Kim Holmén, international director of the Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI), which operates the ship.

During this six-month expedition, rotating shifts of international scientists will be collecting comprehensive data on sea ice, from when it forms in winter until it melts in spring. The data will underpin efforts to model and predict the future of sea ice and its effect on the Arctic ecosystem, global weather, and climate.

Staking the Territory

The first order of business, once the ship was tied to its new floe, was to survey the real estate. Sea-ice physicists disembarked with a snow depth gauge and an electromagnetic instrument that measures the thickness of the ice (and snowpack) by inducing an electric current in the seawater beneath. They found that in some areas, the ice was as thin as 35 inches (90 centimeters)—indicating it likely formed only a few months ago. In others it was nearly ten feet (three meters) thick, indicating that the floe had probably survived from the previous winter.

Running these instruments around a one-mile (1.5-kilometer) perimeter, twice a week, the researchers will monitor the drifting floe as the season changes. "Because we're still in winter, we expect the sea ice to grow and more snow to accumulate," explains Gunnar Spreen, a NPI sea-ice physicist. "But one of the things we want to find out is: When does the melting begin?"

Other scientists followed the physicists onto the ice. Maps of the area were drawn, bamboo stakes planted, and electric cable laid out across the floe. Like homesteaders, the scientists began establishing their camps.

Beneath a blue tent, oceanographers bored a hole in the ice through which they will gather data about ocean currents and water composition at various depths. Meteorologists erected a 33-foot-high (10-meter) mast to collect weather data and a smaller structure to measure greenhouse gases.

Meanwhile, in the crow's nest high above the Lance, an atmospheric and ice chemist with the British Antarctic Survey installed instruments that detect airborne snow and sea-salt particles, which affect cloud formation and how much sunlight gets reflected by the atmosphere.

Elsewhere on the floe, researchers from CNRS, the French governmental science agency, drilled a hole through which they'll deploy a cutting-edge oceanographic float loaded with sensors. It will register the amount of light that penetrates the ice to the water below—and the amount of microorganisms that are there to absorb it, as measured by the concentration of chlorophyll.

No Day at the Beach

Fieldwork in this forbidding environment, where temperatures regularly plummet to -22°F (-30°C), requires a dress code akin to armor. Before leaving the mother ship, a scientist is outfitted in an insulated jumpsuit, balaclava, padded hat, goggles, mittens and then gloves, hand warmers, headlamp, walkie-talkie, work belt, and "moon boots."

Back on the island of Spitsbergen, where the expedition began, participants underwent rifle training for defense against polar bears. Someone in each working team is designated to be a guard and packs a flare gun and 30-06 caliber rifle. A reporter who is not gathering scientific data turns out to be a prime candidate for this duty.

Built in the late 1970s for the original purpose of fishing and sealing off Greenland, the Lance is an elderly but capable vessel. It contains tiny living quarters with bunks, storage areas that the scientists use as laboratories, a workout room, and a tanning bed—a source of vitamin D during the dark polar winter. The ship has wood paneling, framed pictures on the dining room walls, and plaid curtains over the portholes. Layers of frost have accumulated on the inside of the glass.

The feeling is of a homey Norwegian hunting cabin, where one wears a snowflake-patterned sweater and snacks on waffles and jam in midafternoon.

It was during lunch the other day that a sudden announcement crackled over the ship's public address system: "Polar bear on the port side." Abandoning plates of roast chicken and creamed Norwegian herring, everyone raced up to the bridge. The bear was about 650 feet (200 meters) from the ship, trotting across the ice floe. It sauntered to the perimeter of the study area, turned around, and stood on its hind legs. It climbed over pressure ridges—slabs of sea ice pushed up by colliding floes that resemble a patchwork of crumbling stone walls—and lifted its nose in the air to catch a scent. It slid down mounds of snow on its tummy and rolled over like a dog in grass.

Striding alone across the white icescape, the yellowish bear was a magnificent sight—but also an unwelcome one. The safety officer rode out on a snowmobile and shot a flare at the animal. Håvard Hansen, the NPI's chief of Arctic operations and a former soldier, remarked: "It's important to scare them off as soon as possible, so they know this isn't a pleasant place to stay."

The flare did little to deter the curious bear, however. After nightfall, an oceanographer out on the ice caught the animal in his headlight at close range. The following morning, it was spotted running off with a reflective vest from a GPS station located beside the ship. From the bridge throughout that day, I watched the bear through binoculars as it rambled a comfortable distance away. Presumably, it was watching us too.