Solar Plane Takes Off on Round-the-World Quest

Swiss pilots hope to complete journey in five months.

Little more than a century after the Wright brothers launched a gas-powered airplane from a sandhill outside Kitty Hawk, a team of Swiss explorers took off Sunday for their own run at aviation history, in a plane fueled only by sunlight.

Strapped into the cramped, single-seat cockpit of a plane called the Solar Impulse 2, former fighter pilot André Borschberg lifted off just after 11 p.m. EDT Sunday from a military airport near the Strait of Hormuz and began the first leg in a quest to fly a solar-powered craft around the world.

Borschberg will head first to Muscat, Oman, gradually climbing toward 28,000 feet (8,500 meters) as a vast array of solar panels stretched across the wing tops and fuselage drink in sunlight and power the craft’s four electric engines. After Oman the plane will continue east, visiting cities in India and China before attempting to reach Hawaii on a perilous, multi-day crossing of the Pacific.

The journey is expected to last five months and cover some 21,000 miles (33,800 kilometers), with frequent stops along the way where Borschberg will trade off flying duties with his partner-in-adventure, Bertrand Piccard. If their circumnavigation is successful, the men will be the first to break the fuel barrier—crossing immense distances, flying day and night, without consuming a drop of gasoline.

“This is the future,” said Piccard, a psychiatrist and adventurer who in 1999 was first to fly around the world in a gas balloon. “It’s another way to think, to fly, to promote sustainability. We’ve come a long way since the Wright brothers.”

The broad concept for a zero-fuel flight came to Piccard on that balloon trip, when he spent nearly 20 days drifting above nations and cities, oceans and islands with his co-pilot, Brian Jones. Sometimes the men were whisked along by the jet stream, sometimes they were caught dead in atmospheric doldrums. Though they brought 4 tons of helium and propane gas to keep them afloat, they nearly ran out toward the end and were almost forced to ditch.

Piccard, who had made two previous, unsuccessful bids at the balloon record, said he became obsessed with fuel as the possibility of a third failure crept closer. He said he began to see fuel as an obstacle—in his own adventure and also in terms of human progress.

“We are addicted to fuel,” he said. “But we have clean technologies now that can change that, and change the world.”

Two years after setting his balloon record, Piccard approached the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology with his plan for solar-powered circumnavigation. Intrigued, the institute commissioned a feasibility study and chose Borschberg to lead it.

At the time, Borschberg was an entrepreneur with experience in tech start-ups and in the semiconductor industry. He had for years also flown jets in the Swiss air reserves. His team concluded that Piccard’s idea was possible—though just beyond reach of the day’s technology. But those limitations only fired Borschberg’s imagination, and in 2004 he joined Piccard to found the Solar Impulse project.

“Many people told us they didn’t think our project would be possible,” Borschberg said.

For the last decade the men have worked to haul their plan into reality. Piccard courted sponsors and developed the core ideas of sustainability and exploration behind the mission; Borschberg assembled a team of engineers and designers to tackle the challenges of solar-powered flight.

While many solar aircraft have flown successfully before, including small piloted models and massive remote-controlled drones, all have been relatively fragile and none has ever attempted the multi-day transoceanic journeys awaiting Piccard and Borschberg.

Engineers said that to accomplish such long flights, their plane needed to balance two opposing parameters: it would need to be very big, while weighing as little as possible.

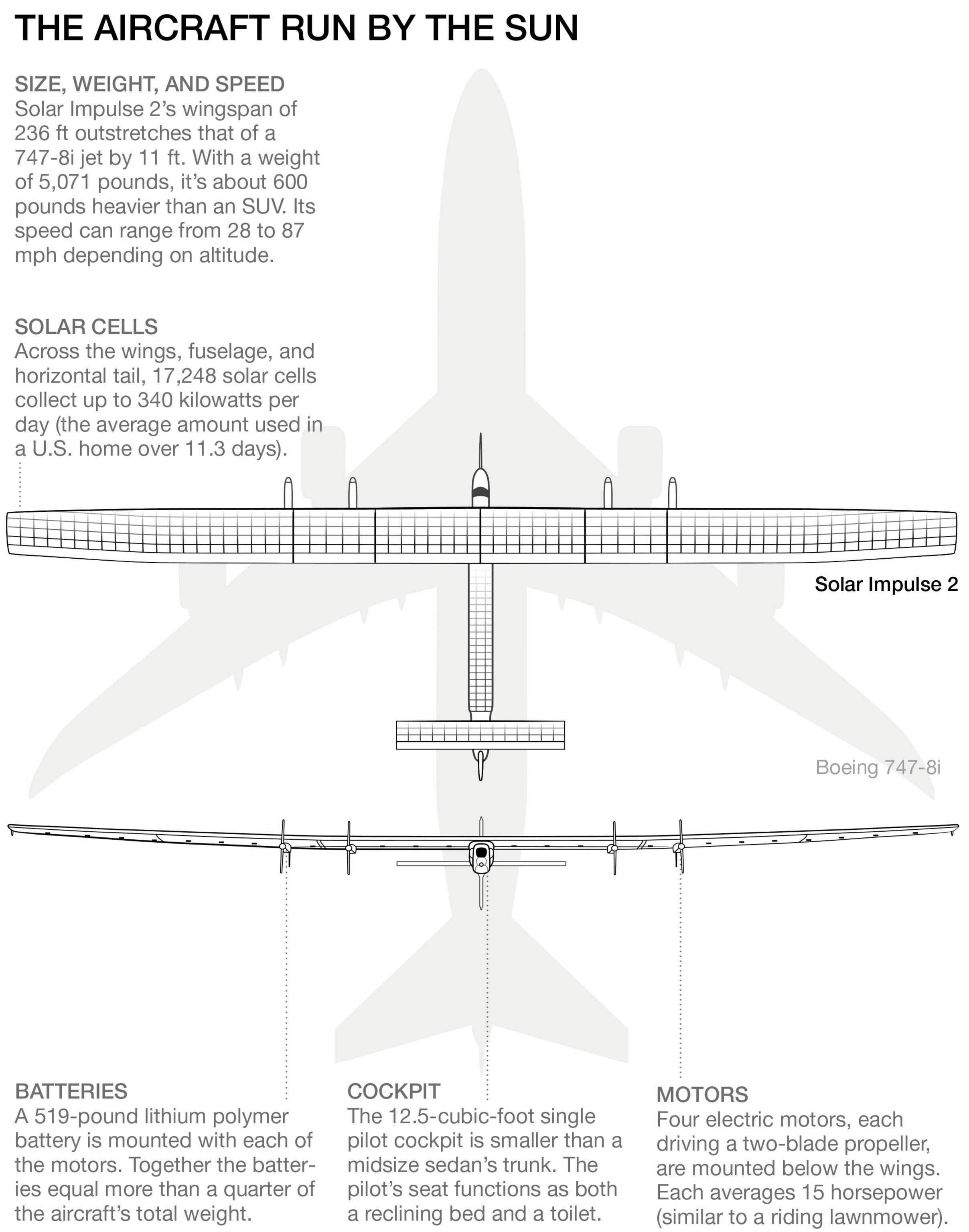

The requirement for size grew out of the need for power. Even the most advanced solar-driven engines still don’t provide very much thrust compared to gasoline engines, so more solar panels were required to launch the plane and keep it flying. The designers’ answer was to line every sun-facing surface of the plane with more than 17,000 solar cells, each about as thick as a human hair.

Carrying most of this photovoltaic assembly, the Solar Impulse 2’s wings reach 236 feet (72 meters) across—wider than than the wingspan of a Boeing 787-8, an airliner built for more than 460 passengers.

To save weight, Borschberg said his team searched for the lightest materials possible, paying close attention to notoriously dense parts, like the plane’s four batteries, which, at 519 pounds (235 kilograms) apiece, are among its heaviest components.

Engineers spent years fine-tuning and test-flying. They trimmed every unnecessary kilo, turned the cockpit into a cell smaller than a car trunk, and composed the plane’s skeleton from custom-made carbon fiber. Even the pilot’s seat was reconfigured for efficiency: it doubles as a toilet and reclines into a short bed.

As it lifted off this morning (Monday in Abu Dhabi, Sunday night in the United States), after years of refinement and experimentation, the Solar Impulse 2 weighed just over 5,000 pounds (2,268 kilograms), similar to some large SUVs. No featherweight, Borschberg admitted. But still, not bad.

"The aviation world did not have the technology to build this," Borschberg said, a few days before launch. "So we had to bring all of these things together to do it. We stretched the technology to the edge, and then we tried to find companies that would work with us."

With the groundwork finished and the plane finally airborne, the most trying and potentially dangerous parts of the journey await.

Most of the legs will require a dozen or more hours of flying, during which the pilot will guide the aircraft up to 28,000 feet to gather the day’s maximum load of sunlight. While at that altitude, he will face extreme cold, and the possibility of altitude sickness, similar to climbers on Mt. Everest.

But at least three legs, from China to Hawaii, Hawaii to Arizona, and New York to Europe, will last far longer—up to five days each. Flying far from runways and beyond reach of easy rescue, with nothing but ocean below, the pilots will face the vagaries of weather and also the limits of human endurance.

A mission control center in Monaco will constantly monitor atmospheric conditions and the pilots’ vital signs. A team of meteorologists, computer scientists, pilots and medical personnel will advise Borschberg and Piccard and help them choose the safest, smoothest route.

In addition to their support team, the pilots will have an onboard oxygen supply, energy drinks and protein bars, and specially designed clothing to help keep them warm, including black UGG boots. There is also a parachute and a life raft.

Finally, each man has drawn up a regimen to help him rest, focus, and remain mentally well during the days and nights aloft. Periodically during their flight, the pilot will give control over to an autopilot computer, which will allow him to nap. Both men also plan to employ yoga and meditation techniques on the reclining seat, and Piccard said he would use self-hypnosis to quickly enter a restful state—a method he developed during his years as a psychiatrist.

"Hypnosis is a simply another kind of exploration, spiritual exploration," he said. "All of this—the flight, the clean energy, hypnosis, meditation—it’s all about learning and trying to improve life on this planet.”

For Piccard, the adventure ahead fits into family tradition. He is the son and grandson of explorers who, during the last century, become famous for their accomplishments.

In the 1930s, Piccard’s grandfather, Auguste, a physicist, became the first human to reach the stratosphere aboard a pressurized capsule carried aloft by a balloon. Thirty years later, Piccard’s father, Jacques, descended to the deepest point on the seafloor—in the Challenger Deep of the Mariana Trench—in a submersible he designed with Auguste.

During his childhood in the 1960s, Bertrand Piccard lived for a time in West Palm Beach, Florida, while his father worked in undersea research with the U.S. Navy. Among his father’s friends and associates were many of the rocket scientists and astronauts involved in the American space program. Men like Wernher von Braun, Neil Armstrong, and Buzz Aldrin were regular visitors to the Piccard home.

Surrounded in that rich stream, Piccard said he early decided to become an explorer, too.

“When you see what my father and grandfather did, it was not to make a record,” he said. “It was to be useful. Exploration has to be useful. This is why I launched this project. I think we can make a huge difference.”

Neil Shea is a writer based in Boston and a longtime contributor to National Geographic. You can follow him on Instagram @neilshea13.