Why the Life of a Shepherd Has Value In Today’s World

It isn’t about subsidizing a tiny number of farmers for nostalgic reasons. It’s about defending a special way of being, says author.

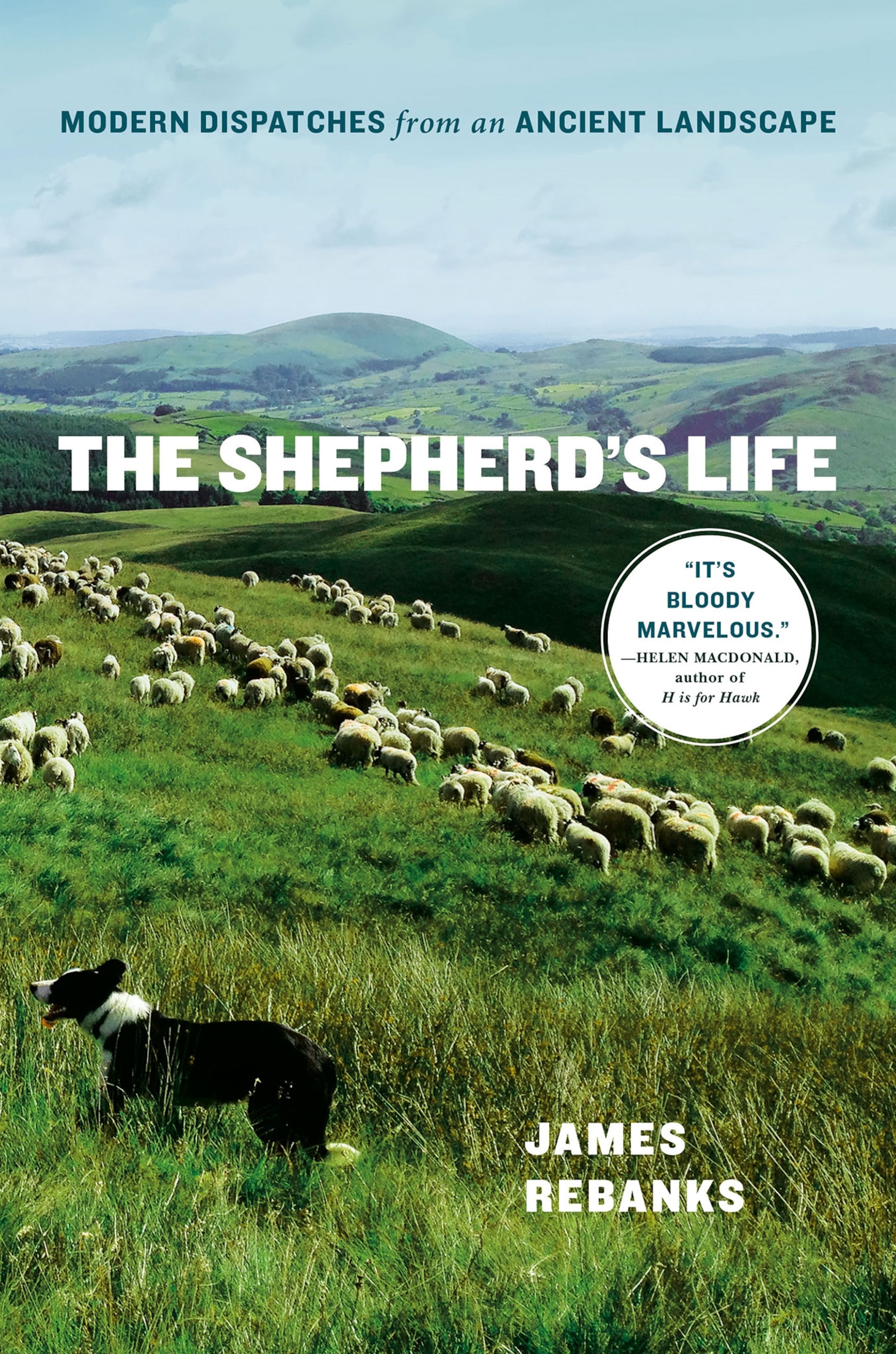

He’s been called Twitter’s favorite shepherd, his name is James Rebanks, and for more than 500 years his family has raised sheep in England’s rugged and beautiful Lake District. It was an unchanging way of life they were proud of. But as he grew up, he realized that some in the modern world regarded sheep farming as dirty, provincial and irrelevant. The Shepherd’s Life: Modern Dispatches From An Ancient Landscape is his response: a celebration of one farming family and their vanishing way of life.

Talking from his farm in Matterdale, he explains how the Vikings brought Herdwick sheep to Britain; how nature conservation began in the Lake District; why a shepherd is nothing without a sheepdog; and why it is important to protect ancient ways of life, not just in Britain, but all over the world.

You come from a long line of sheep farmers. Tell us about the Rebanks family.

The first mention of the Rebanks in the written records is in 1420 in a parish almost within sight from where I live now. They were small sheep and cattle farmers. Occasionally, they got up to being almost yeoman farmers, sometimes owning their farms. A century later they’re back as agricultural workers or tenants on small farms, but always doing more or less the same thing in more or less the same place; and always reasonably well thought of in their community because they tried their best to be good at what they did.

Your farm is in Matterdale in the Lake District. Situate us geographically.

If you head north up England, Cumbria is the last bit on your left-hand side before you get to Scotland. The Lake District is basically a small mountainous area of about 800 square miles. But it’s got a very important place in the English imagination. It was one of the first places in the world where people like the poets Wordsworth and Coleridge realized you had to defend old places and old ways of life. It’s said that every protected place on earth, every national park or world heritage site, goes back to some words of William Wordsworth, who said of the Lake District–and I’ll probably misquote this–that every man who had an eye to see or a heart to feel should have a stake of ownership in this landscape. And from Wordsworth onwards, through Beatrix Potter, it’s had an iconic place in the English imagination.

We have to find clever ways to protect...what’s known as the cultural landscape.

Immortalized by poets, the Lake District has attracted millions of tourists. You sometimes feel the guests have taken over the guesthouse, don’t you?

Like most people who look objectively at tourism you have to see a lot of good things it brings. The 16 million visitors a year that come here spend 1.1 billion pounds. More than half of the people in our landscape now live directly or indirectly from tourism. So I certainly don’t want those tourists to go away.

But there are only 43,000 residents and about two to three hundred families who sustain the farming culture I love and have written about. That creates a real challenge. And it’s now a global challenge.

All over the world you have a relatively small number of people, in a much-loved place, sustaining its landscape, history and culture, with a much larger number of people coming in. That creates an imbalance of power and economic might. So we have to find clever ways to protect the things that people cared about in the first place: what’s known as the cultural landscape.

The book is dedicated to your grandfather. Tell us about him and your relationship.

The book is about growing up and becoming a man, I suppose. In a family business and tradition, you’re thrown together for better or worse and your lives are shared.

The early part of the book is about me effectively hero-worshipping my grandfather. He was an old hill farmer, and I still love him dearly twenty years after he died. He worshipped me as well, in a way. I was the blue-eyed boy who was going to take the farm on and keep his life’s work going.

My relationship with my father, as with many lads growing up, was much more difficult. We would sometimes row like cats and dogs, and do all sorts of cruel things. But we ended up great friends. One of the last things he did before he died this year was to read my book. Because I knew my father was dying of cancer, the book became like a letter to my Dad. I wanted him to know much I respected him and loved him. And till my dying day it’ll be a great comfort to me that I was able to do that. [Chokes up] Sorry, you’ve got me crying now.

You say that “landscapes like ours were created by and survive through the efforts of nobodies.” What do you mean by that?

I’m fascinated by culture and it strikes me that we still have a very hierarchical, ‘Great White Man’ view of culture when it comes to the countryside. Every year people publish books about the culture and history of the Lake District, which barely mention people like my grandfather or my father.

I wanted to kick back against that, because this landscape wasn’t created by the efforts of great men. It’s a landscape created, sustained by, and made very special because of people who’ve never made it into books, who nobody knows the name of unless you’re one of us. I mean ‘nobodies’ as a great compliment, not as an insult.

People like my grandfather and my Dad and their peers were never written about in books. But, collectively, they have done something great, and I wanted to make that point as well as I could.

Your life takes a dramatic turn when you go to Oxford University as a mature student, though you couldn’t actually write. Did you feel out of place?

I felt very, very out of place. [Laughs] This might sound arrogant, but I never worried about whether I was bright enough. Shepherds put a premium on being smart and knowing the things you need to know. And I wasn’t a kid when I went to Oxford. I was in my early twenties, and I knew I was smart in a worldly sense.

But socially and culturally I felt very alien. In fact, I tried to bottle it. The first evening, I rang my wife, who was then my girlfriend, and said, ‘I need to come home; I don’t belong here.’ To her credit, she said, ‘don’t be ridiculous, toughen up and get on with it.’ So I did.

But I had very little in common with people who’d done all these amazing things at school and travelled all over the world and spoke multiple languages and could play lots of musical instruments. [Laughs] I could do none of those things. So I was this strange creature in the midst of it all.

Among the central characters of the book are Herdwick sheep—a species perfectly adapted to its environment. What makes them so special?

Herdwick sheep have been indigenous to the Lake District for the last thousand years. Local legend has it that they came on the boats with the Vikings. Recently, they’ve done genetic studies and it appears their nearest relatives are on the islands of the Wadden Sea just off Denmark, and in Sweden, Norway and Iceland.

So the local myth is true: they are Viking sheep. [Laughs] They’re the toughest mountain sheep in Britain. They also happen to be very productive. There’s another feature of Herdwicks that is essential: they’re “hefted,” which means they’re culturally conditioned to live on one tiny part of the mountain come hell or high water. That’s where their mother taught them to graze, and there’s an unbroken ancestry of these sheep teaching their daughters to do that, as far back as 1000 years.

A shepherd is nothing without a sheep dog. Describe that relationship.

A shepherd without a sheep dog isn’t a shepherd. You have to gather the sheep in the mountains and the sheep are twice as fast as a man and on a mountain they’ll be quite as clever as a man. You could take 300 people to our fell [mountain] without dogs and you wouldn’t be able to lock down a single sheep. But six men and women with ten sheep dogs could gather that whole fell.

So the whole thing is made possible because of sheep dogs, usually border collies, and the relationship is crucial. I have a bitch called Floss and a dog called Tan. They’ve just had puppies, and they’re the most important part of my working life. They are one way by which a shepherd is judged. Other shepherds think you’re useless if you haven’t got a good sheepdog. If you have a very good sheepdog, it speaks about your skill and commitment and knowledge.

Your education brought you a parallel life working for UNESCO. And on a trip to China, you had a poignant encounter with an old woman selling souvenirs by the side of the road.

It was one of many moments where you can see modernity changing people’s lives and not always in ways they like. I met a lady on a hillside in China selling souvenirs. I got chatting to her through the translator and she explained that she was making a lot more money selling souvenirs than she used to.

But her real story was that her family and all of the farmers in the village I was visiting used to be duck and pig farmers. That was how they got their identity and how they felt themselves to be useful in the world. But through a process of gentrification in their landscapes for tourists they weren’t allowed to keep pigs and ducks anymore.

There was a great sadness in that she wasn’t able to do those things anymore. There was a sadness in me as a visitor, too. I wasn’t seeing the real place and its real history. I was seeing a sanitized version of it. And those tensions are happening all over the world.

Why is important to preserve a way of life like yours?

It’s important for the reason it was always important. Wordsworth described the Lake District as a “perfect republic of shepherds”: an ideal example for the whole world of how people could live in their environment and manage their affairs in a more egalitarian way.

Two centuries on from Wordsworth, the world is going through a rapid process of modernization and urbanization. I think we need places like this where different ideas and ways of life hold sway, where older ways of being survive. The 16 million people that come every year to this landscape are in part coming for exactly that reason.

It isn’t about subsidizing a tiny number of farmers for nostalgic reasons. It’s a very contemporary argument about defending older ways of being and not letting everything get swept away by an industrial, cheap food model. It’s not about my self-interest. It’s about us as a society, both in Britain and the rest of the world. It’s about looking at places where special things survive and saying, actually we can keep this alive and it’s good for all of us to do so.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.