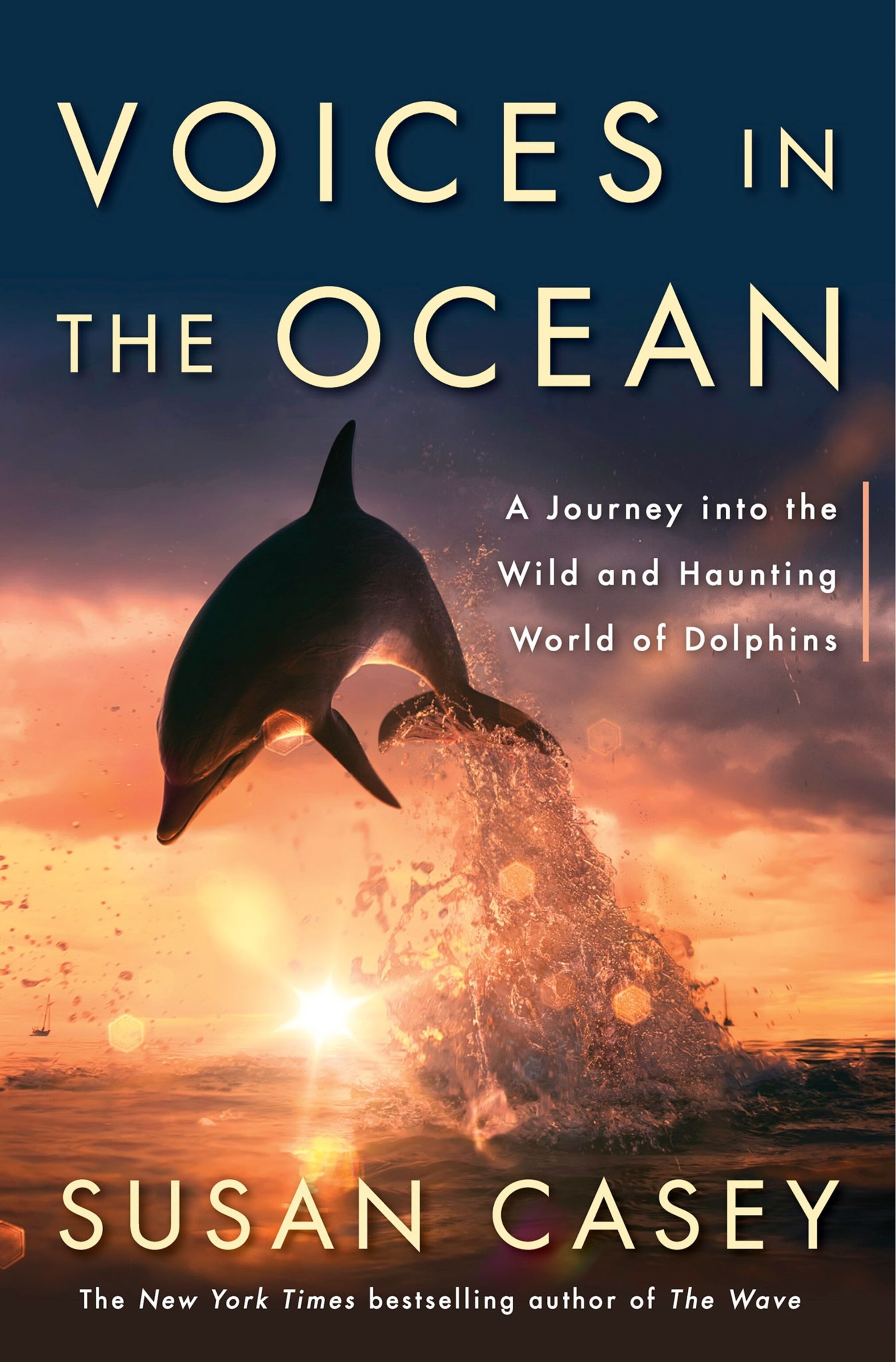

How Dolphins Healed An Author’s Broken Heart

Grief stricken after her father’s death, Susan Casey went to Maui for surf and solace. A pod of dolphins showed up and changed her life.

Susan Casey was living the dream. She had an apartment in Manhattan, a top job as an editor at Oprah Winfrey’s O magazine. Then her father died and her world fell apart.

To try and heal her grief, she went to Maui. She had been a competitive open water swimmer all her life and one day, while swimming offshore, a pod of dolphins surrounded her. The experience haunted her. She gave up her life in New York, moved to Hawaii and began work on her book Voices in The Ocean: A Journey Into The Wild and Haunting World of Dolphins.

Talking from her home in Maui, she describes how dolphins are more than simply cute, smiley creatures; how some people in Dolphinville think dolphins came from outer space; and why, by overfishing or testing underwater sonar for war, we are not just hurting dolphins, we are hurting ourselves.

Tell us how you came to write this book and what happened to you swimming one day in Hawaii.

I was on Maui at a time in my life when I was grief stricken after the sudden death of my father. He was the central part of my universe. Maui became the place that helped me heal.

I had come from New York where I was living at the time and had one more day to swim and surf and soothe myself in the ocean. The weather didn’t cooperate. It was stormy and grey, and the ocean had a mean look. But I decided to go in anyway, not really caring what happened. When I was far offshore, I thought I might see some large creatures; what I didn’t expect were dolphins.

I compete at open water swimming in the ocean and in all my years of doing that, I had never been in the water with wild dolphins. But that day a pod of dolphins came and surrounded me. I had heard from other people that when you meet wild dolphins in the water, it’s very haunting. And that’s exactly how it was. I just couldn’t stop thinking about it. I started becoming obsessed with the notion that these animals were able to make me feel better. How did that happen? Nothing else had up to that point.

You experienced dolphin echolocation. What is happening at that moment?

Echolocation is an amazing adaptation. Fifty-five million years ago they moved from the land to the sea and their bodies started adapting to life underwater. Every single thing you might need to be a successful creature in the ocean – they’ve got it. Sonar is certainly at the top of that list.

Light doesn’t travel far through the water and especially at night they still need to know how to navigate. The sonar emanates through amazing structures in their jaws, up near their blowhole. It’s basically a beam of clicks. Dolphins can send out 2,000 clicks per second; they can aim and adjust each click and the frequency of the click and send out two click streams at once in different directions. What they’re doing is creating pictures three dimensionally that show them, much like ultrasound, what they’re looking at.

You hung out with some pretty kooky people while you were researching this book. Talk to us about Dolphinville.

Dolphinville is not a place, it’s a state of mind. I had read about Dolphinville when I was looking around at dolphin sources and heard of the woman who was at the center of it – Joan Ocean. I was interested in the group because they represented something quite unique about dolphins: that they have a central place in the New Age World.

Dolphinville is a group of people on the Kona Coast of Hawaii, who go out in the water for hours at a time every day to swim with the wild dolphins. They have a range of beliefs about the dolphins, from “these are highly intelligent creatures,” to “these creatures came down from outer space.” [Laughs] They’re absolutely lovely people!

Human and dolphin interaction is recorded as far back as 77 A.D. Tell us how dolphins often help humans in trouble in the ocean.

There’s an even longer history than that, a pre-history. In Crete, there are paintings of dolphins that date back to 1600 B.C. The Ancient Greeks also incorporated them into the myths, like the story of a dolphin saving Dionysius. It continues today. I spoke to several people who had had encounters where dolphins had helped them and I can count myself among that group. My favorite example happened to a scientist named Maddalena Bearzi, which she writes about in her book, Beautiful Minds.

She was working with a pod of dolphins off the coast of California, following some bottlenose dolphins that were looking for food. They found some sardines and started herding them into a cluster, which is a lot of work. Then, all of a sudden, one dolphin took off and headed straight offshore at top speed. All the other dolphins then started following it, swimming away from the fish until they were about three miles offshore. They formed a circle. Bearzi and the other scientists followed in a boat and in the center of the circle they found a teenage girl’s body floating. She had attempted suicide but was still alive. She had a plastic bag wrapped around her neck with identification and a suicide note. The scientists were able to save her because the dolphins took them to her. Isn’t that just astonishing?

Why do people project onto dolphins the idea they are happy-go-lucky, mystical creatures?

We tend to project what we want to see because here is an animal that always seems to be smiling. But they’re very complicated individuals, with a range of behaviors that mirror ours. And that makes them more interesting. They can be aggressive and intimidating. If you see a dolphin jaw clapping, it’s like watching a dog bite somebody. In certain parts of the world, bottlenose dolphins form male alliances to corral female dolphins and keep them from escaping. Then, of course, there are orcas, which can rip apart whales. It’s not all flowers and sunshine in the dolphin world.

There is some very interesting research going on with dolphin communication. Unpack that for us, specifically Denise Herzing’s work?

She is the founder of the Wild Dolphin Project. She has been studying for a very long time a pod of very friendly, curious spotted dolphins on the Bahama Banks. She has created a pattern recognition software program that she uses to hopefully translate the sounds that they’re making into English. They were working with this particular dolphin and the dolphin whistled the word, “sargasso”, which was the seaweed that it was actually playing with. She’s in a long tradition of scientists, beginning with John Lilly, who realized that, even if you cannot scientifically call it a language, it is a language for them.

As part of your research you met someone known as the Darth Vader of Dolphins. Tell us about him.

Chris Porter was a Canadian guy I had seen in documentaries about the Solomon Islands. He had gone to the Solomon Islands because he heard that the islanders hunt dolphins for their teeth. The teeth are even used as a currency to buy and sell women. In about 2001, Porter began to recruit the traditional villagers, who were capturing dolphins – and by the way, it was a lot of dolphins – then decapitating them and prying out their teeth. He convinced them to capture dolphins for him, leased an island called Gavutu, which had been a seaplane base in World War II, first for the Japanese and then, for the U.S. - and proceeded to cause a lot of havoc.

I can’t speak to his motivations. He told me he was trying to find a way for them to stop killing so many dolphins. But what actually happened was that, as a result of his presence, dolphin hunting ratcheted up dramatically. The Solomon Islands became a major source for dolphin traffickers and Solomon Islands dolphins ended up on airplanes going to Dubai, China or the Philippines.

If we make the oceans uninhabitable for these creatures through overfishing, or pollution, or blasting sonar through the water, we don’t just hurt them. We are hurting ourselves.Susan Casey

All the environmental groups began to flock to the Solomon Islands and Porter was dubbed ‘The Darth Vader of Dolphins.’ Eventually he was exiled from the country, all of his dolphins died and the Solomon Islanders went and ripped apart his island. I caught up with him back in Canada, where he was licking his wounds and trying to make amends. He was one of the first trainers of Tilikum, the orca that ended up killing three people at Seaworld, and is now trying to do something about the plight of captive orcas. He was this giant ball of emotion and contradiction; dark and light. A fascinating character.

What is our moral imperative regarding these intelligent creatures who are often kept in captivity and made to perform tricks?

When you learn everything there is to learn about dolphins, you discover that they have families; they call themselves by name; they have huge, complicated brains that they’ve had for 35 million years; they are perfectly adapted to their environment; they live in harmony, in their own way, in the most dominant ecosystem on Earth. So I think our moral imperative is to treat them with respect. For our sake, as well as theirs. If we make the oceans uninhabitable for these creatures through overfishing, or pollution, or blasting sonar through the water, we don’t just hurt them. We are hurting ourselves.

How have dolphins changed your life?

Since I met the dolphins in Honolua Bay, my life has changed completely. At the time, I was running a magazine with about 70 editors and other employers working under me. When I started thinking about dolphins, I realized that they had really touched my heart in a way that I had to look at very carefully. It was a time in my life when I was wondering how I would go on.

I hesitate to say something wacky, like, “The dolphins showed me where my heart was.” Writing a book is a five-year endeavor. I write about science and a lot of other things and I take my work seriously. But I really am following my heart, in writing about the ocean. And it was at that moment in Honolua Bay that I realized exactly where my heart was.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter.