Putting Human Faces on India’s Mega Problems

An Indian-American author finds hope for humanity in her homeland.

Like China, India is a leviathan among the world’s emerging economies. As with China, economic and social progress have come at a price: pollution, depleted natural resources, and overpopulation.

Presenting an overview of these issues in a country of 1.2 billion people, with a stunning diversity of landscapes, faiths, and ethnic groups, can be bewildering—and dull.

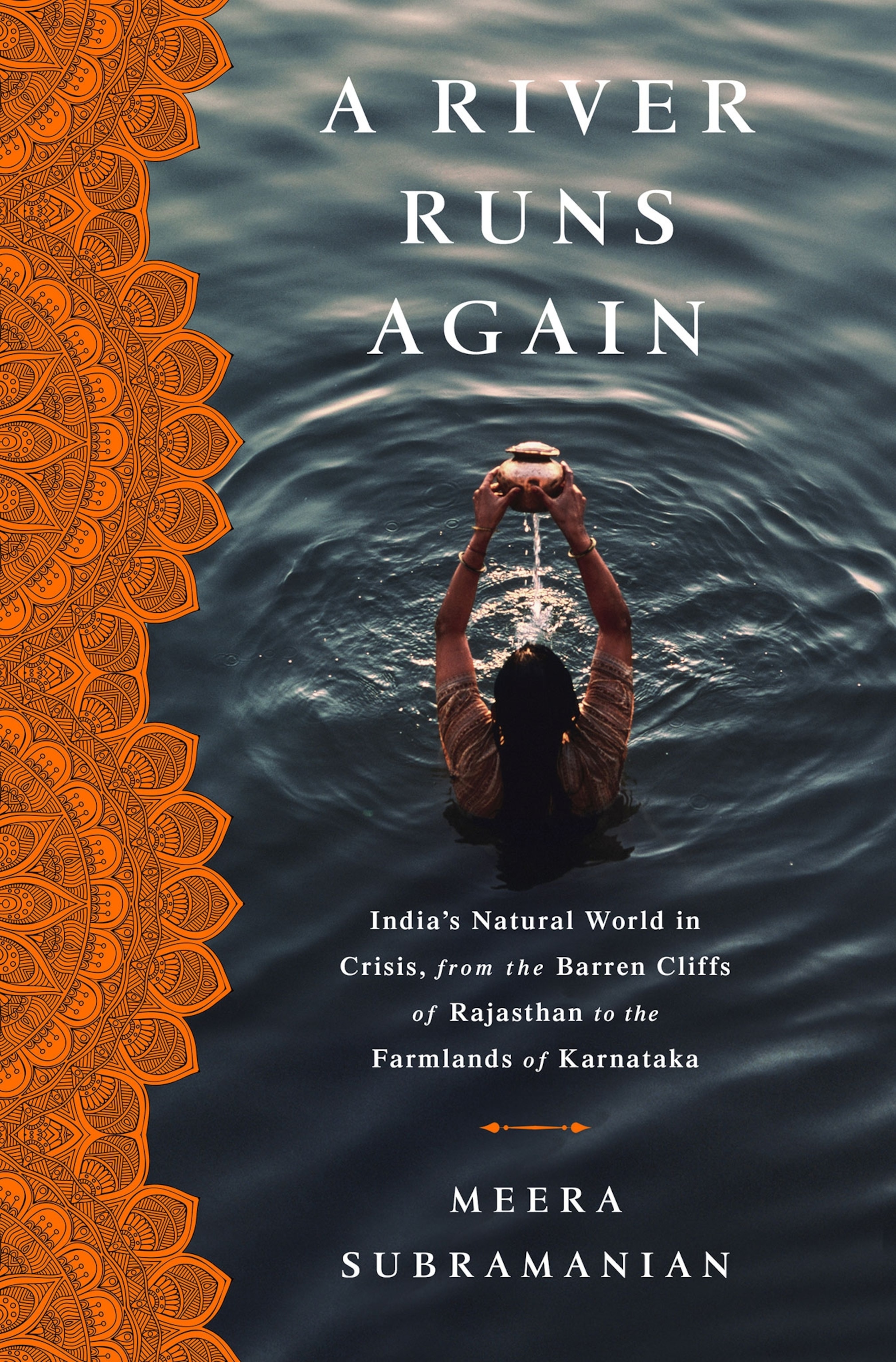

By concentrating on the stories of individuals, Meera Subramanian, author of A River Runs Again: India’s Natural World Crisis, From The Barren Cliffs of Rajasthan to the Farmlands of Karnataka, puts a human face on seemingly insurmountable challenges.

The cancer rate in Punjab is higher than both Indian and international averages.Meera Subramanian

Talking from her home on Cape Cod, she describes how a “Rainman” brought water to Rajasthan; why a new kind of wood stove is helping reduce pollution while raising the wages of rural women; and how a turban filled with money became a symbol of hope and cooperation.

Your book uses an interesting structure to discuss nature in India and the problems the country faces. Explain the five elements.

Looking at the story of the environment of India can be daunting, so I wanted to find stories that brought the issues to readers in a more personal way, both in terms of the people and the subject matter.

The five elements—earth, air, fire, water, and ether—seemed like a great way to do that. The wonderful thing about the elements is that they’re cross-cultural. All cultures have used them to try to shape and define what makes the world we inhabit. Plato first used the word “elements,” but they’re found in Islam and in ancient Greek and Chinese culture. I focused on the Pancha Mahabhuta elements used in India.

The Green Revolution in post-World-War II India ended up being anything but green. Tell us about the crisis many Indian farmers are facing today and the new “organic revolution.”

Punjab is the breadbasket of India and the place where the Green Revolution was launched in the ’60s. The pesticides and seeds were distributed free or at highly subsidized rates. They were incredibly productive in the beginning, so it seemed like a win-win solution. But there wasn’t enough thought given to what this would look like further down the road.

Part of the success of the Green Revolution was that the seeds grew wildly—but they needed tons of water. Forty years later, thousands of wells have depleted the aquifers, and fertilizers and agricultural runoff have infiltrated the water systems, so you’ve now got contaminated water.

It’s always difficult to prove causality, but the cancer rate in Punjab is higher than both Indian and international averages.

India has a huge population. They’ve dealt with famines as recently as 1943, and they don’t want to face that again. But there are farmers now who are questioning the value of the Green Revolution and whether there’s a way to bring back traditional methods of growing crops.

Tell us a bit about your own Indian heritage and how it informs this book.

My father is from India. He came to the U.S. when he was 25 and, against his family’s wishes, ended up marrying an American woman of European descent. It was very controversial at the time, and I’m grateful that he didn’t sever ties with his family.

He thought it was important for all of us to know his homeland. I’ve been going back and forth to India ever since I was 18 months old. Every few years we would go and be connected to the family there, which is a large Indian clan in South India. [Laughs]

After I finished college, I began doing environmental nonprofit work. I was grappling with questions of how to live sustainably in my own life, and each trip back to India gave me a fascinating new look at what was happening there.

It was growing incredibly rapidly, especially after the economic reforms of the early ’90s. What I was seeing in India was what other emerging nations are dealing with around the world: increased population, limited natural resources, and climate change. How do we make this work, not just today but for the long term?

You discuss water issues through the eyes of the Rainman of Rajasthan. Introduce us and explain what a johad is.

A johad is a small check dam usually made of earth or stones. In places with limited rain that falls at particular times, you try to catch it by making little puddles and ponds. That way the water has a chance to seep down and replenish the aquifers below. Otherwise, the rain just runs off because of erosion.

The Rainman, whose real name is Rajendra Singh, was a Gandhian activist. He trained as a doctor and went from village to village trying to start schools or medical centers. In one village in Alwar District, the village elder sat him down and gave him a good talking to. “We don’t need all that stuff! We need water!” He took Singh to one spot and said, “See right there? If you build a johad, it will help bring the water back. But nobody’s doing it. You need to do it!”

The Parsees lay out their dead for the vultures to eat.Meera Subramanian

The Rainman spent the next three years digging johads, eating rice and lentils. Everybody thought he was crazy until the wells started to replenish. So they decided to replicate it throughout the area by building thousands of johads, each flowing into the next.

As a result, wells that had dried up started to come back to life; agriculture could revive; livestock could be fed again; and men who had been leaving for the cities could return home and work the land again.

Smoke from cooking stoves is a huge health and environmental issue in much of the world. Tell us Mouhsine’s story and how a smokeless stove gave one woman confidence?

Mouhsine Serrar is Moroccan-born, now living in India. With his company, he’s been developing Prakti stoves: fuel-efficient, woodstoves that can burn biomass, whether wood or agricultural field residues. He told me that he met a woman, who said that these stoves were getting her a better rate for work as a day laborer. He said, “Oh, you must be exaggerating. These stoves can’t have that much of a beneficial effect on your life.” She said, “Yeah, if I don’t smell like smoke, people don’t think I’m just a poor laborer, and I’m valued more in the market.”

In the 1990s, the white-backed vulture was as common as the crow, but by 2000 the population had plummeted by as much as 99 percent. What happened? And what needs to be done to bring them back to India where they’re an important part of the ecosystem?

They were an incredibly important part of the ecosystem. There are 1.2 billion people in India, and they produce a lot of debris. There are also interesting cultural dimensions. If there is a dead cow, Hindus won’t eat it, because of religious restrictions. Muslims will not eat something that isn’t butchered in the Halal manner. There are also the Parsees, a religious group found mostly in Mumbai, who lay out their dead for the vultures to eat. That system fell apart when the vultures disappeared.

Vultures were literally falling out of the trees, dead.Meera Subramanian

Vultures were literally falling out of the trees, dead. No one knew why. But they finally figured out it was Diclofenac, a mild anti-inflammatory, like Ibuprofen. Humans had been taking it for decades with very few side effects. But for some reason if a vulture eats a dead cow that has been given Diclofenac, they develop renal failure and die.

They banned veterinary Diclofenac back in 2006, but the black market thrives in India, so it’s still widely used. Just recently, there was a big victory for the vulture conservation community: The Indian Government banned the sale of large vials of the drug. These made it easy for farmers to use on their cows because they didn’t have to pop open a bunch of tiny vials. But much more still needs to be done.

Pinki is an amazing young woman whose work inspires self-rule of a new kind. Tell us about her and how she’s educating young people in India.

[Laughs] Pinki is an amazing young woman. So often we hear of young Indian women who leave home for the city. Pinki was a very traditional young woman. She was an excellent student, but when she turned 16 her family told her it was time to get married.

She resisted—not by running away from home or acting defiantly. She wrote a letter to her father, pleading with him to let her finish her studies and wait until she was older to get married. He listened to her, and she eventually got a Masters Degree from Leeds University, in the U.K. She is now educating teenagers about reproductive and sexual health in Bihar, one of India’s most challenged states, with some of the highest birth rates and youngest brides.

Tell us about the death ritual with the turban—and the metaphor you found wrapped inside it.

I stumbled upon this ceremony when I was in Rajasthan with the community building the johads. I didn’t really know what I was seeing at first. But afterward they filled me in. This man’s father had died. The community stepped in, with each person contributing a small piece of white cloth and a little money, which were wrapped around the head of the dead man’s son.

Eventually, the turban got so big he could hardly stand. But he stood there stoically until it was literally two feet across and eighteen inches high. It was so huge that the community had to physically help him stand up. There were women standing around the edge of the group, who started singing, then they all drifted off into the twilight.

That scene stuck with me as I was working on the book. I didn’t understand why. It didn’t seem to have anything to do with johads or cook stoves or women’s health. But it lingered with me as a metaphor for the weight we all carry. Luckily, my father is still alive. But I know lots of people who have lost their fathers. There’s a terrible weight to losing somebody, like you’re taking on the mantle of responsibility that the prior generation carried.

That’s what I saw in that turban and the way the community supported that man. It’s a big weight—but if we all do this together we will make it work.

You eventually came to think that the question you asked people you interviewed—“Do you have hope?”—was the wrong one. Why is that, and do you have hope?

We have to hope! There’s no way to go forward without believing we can continue to make this planet work for all of us—and for those who have yet to come.

It’s not without its challenges. There’s a lot of tough news out there. But there are a lot of people doing amazing things. When I was asking people, “Do you have hope?” it was a binary question: Yes or No. I realized that was not the right question.

“To hope” is much more active. You hope it’s going to work; you hope girls can stay in school; or that we can clean up the air by not cooking on open fires. It becomes an active, engaged way to be in the world, rather than ticking a box saying Yes or No.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter.