Your Baby’s Brain Holds the Key to Solving Society’s Problems

Author’s advice to parents: Quality time with your baby means tapping the three Ts—tune in, talk more, take turns.

Try saying pediatric otolaryngologist. Not easy, right?

According to Dana Suskind, who holds that title at the University of Chicago, our exposure to rich language in the first three years of our lives is critical not just for our ability to pronounce long words but for our overall development and success.

Sadly, Suskind’s new book, Thirty Million Words: Building a Child’s Brain, also shows that our achievements are largely determined by the economic and social environment into which we’re born.

Put bluntly: A child born in low-income Compton, California, is likely to have heard 30 million fewer words in the first three years of life than one born in affluent Greenwich, Connecticut.

Talking from her home in Chicago, Suskind describes how the “Thirty Million Word” initiative is trying to close that achievement gap; why Mark Zuckerberg’s attempt to learn Chinese shows the importance of being exposed to language in infancy; and how the three Ts—Tune in, Talk more, and Take turns—can help solve the world’s problems.

What inspired you to write this book, Dana?

I started the cochlear implant program at the University of Chicago about ten years ago. My experience as a surgeon started my journey into the world of social sciences and the power of language.

Children born into poverty will have heard 30 million fewer words than their more affluent peers.Dana Suskind

Before implantation, children seemed to have no real difference in their potential to learn to talk. But after implantation, it looked very different. Some were able to talk and learn on a par with their hearing peers, while others were barely able to communicate. And the difference was almost always along socioeconomic lines.

That experience set me thinking, what is going on? It’s the same surgery—with very different outcomes. I later learned about the powerful research done by Betty Hart and Todd Risley about 30 years ago. It demonstrated that children born into poverty will have heard 30 million fewer words than their more affluent peers. But the 30-million-word gap is just a metaphor for differences in richness of languages and environments in the early years.

You make it wonderfully simple. Tell us about the three Ts and how they can make a difference in brain development in young children.

When you think about a rich language environment from a scientific standpoint, it’s incredibly complex. But at the most fundamental level, it’s about the three Ts: Tune in, Talk more, and Take turns.

Tune in means, whether you’re changing your kid’s diaper, going shopping, or taking a bus downtown, be interested in what your child is interested in.

Talk more is as it sounds—talking more, using richer language, narrating your child’s day.

Take turns is the most important one. It means viewing your child as a conversational partner from day one. Many parents don’t realize they can have a conversation with a newborn baby. But babies are born ready to learn and are responding to every coo or burp even before they can use their first word.

The fourth T is: Turn off the technology. Whether TV, iPhone, or iPad, technology is all-pervasive. We need to learn how to live with technology, understanding that a baby’s brain needs real live human interaction. Unfortunately, there’s no substitute, no formula, as there is for breast milk, except doing our best to limit technology and interacting with our children.

You ask an important question: “If babies are such computational wizards, why can’t we just sit them in front of the TV and call it a day?” Explain why that doesn’t help learning processes.

Wouldn’t that be easy? [Laughs] Language developed as a form of communication. There was no technology to feed our brains. We needed social interaction for language to “stick.” There are some cool studies demonstrating this. Babies don’t learn from TV or video. It’s the interaction, what we call, “contingent responsiveness,” where you’re responding to the baby’s actual cues, which helps things stick.

What about children over the age of four, who have spent their lives on YouTube or the TV, without the three Ts and reading? Is there no hope for them?

It’s never too late! The brain is always developing and evolving, even for you and me [Laughs] But there’s no period when brain development is as robust as in the beginning, especially for cognitive skills. If we want to be preventative rather than remedial, we need to focus on that period. But that doesn’t mean that you do zero to three and give up on the rest. It’s a continuum. But if we skip the zero to three, it’s going to be very hard to close that gap.

It’s a cliché that positive reinforcement is a good thing. But you give actual data proving this theory—and surprising information about socioeconomic factors and positive reinforcement. Tell us about the Hart-Risley study.

Hart and Risley were born out of the “War on Poverty.” Before doing the study, 30 years ago, they’d done a lot of pre-school interventions working with children living in poverty. At first, the results showed that children during pre-school, ages four to five, who received key interventions looked no different than those who hadn’t received anything. That experience made them ask, “What’s going on in the daily lives of babies between zero and three?

They decided to follow families from all socioeconomic levels, from what they called the impoverished to the professionals and everything in between, until the age of three. They went in once a month and audio-recorded. What they found after analyzing the data is that children born into poverty will have heard, by the end of age three, 30 million fewer words than their more affluent peers. They then coined that brilliant metaphor, the 30-million-word gap—to get people’s attention.

Hart and Risley also found revealing differences in the use of affirmations and prohibitions—“Don’t do this!” “Get down!” “Be quiet”—versus the rich narrative description. All of these, both how parents do and don’t talk to their children impacted not just children’s vocabulary by the age of three. By third grade, they were also seeing impacts on IQ and test scores, which showed this was the beginning of the achievement gap.

You mention the difference between the word “helper” and “help” in eliciting a response from children and between saying to a child “you are so bad” versus “you did something bad.” Explain the importance of language in developing a child’s brain.

The most important thing this journey has demonstrated to me is the power of language in developing our entire selves, our whole brain. Language not just grows your IQ and cognitive ability. It grows all the different aspects of who we are—our ability to do math, our spatial ability, our ability to persevere through challenges, or our self-regulation.

Empathy is the core of what we want in human beings.Dana Suskind

I’m very focused in our program on person-versus-process-based praise. Saying, “You work so hard” versus “You are so smart” can mean the difference between a child persevering through a difficult challenge or giving up.

Empathy is the core of what we want in human beings. It’s important to praise the individual rather than the process. You want the child to think, “I’m such a great helper” versus “that was just a process.”

Conversely, if a child does something bad, there’s a crucial difference between guilt and shame. When you shame somebody, it’s not a constructive thing. You want it to be connected to what they’ve actually done. Saying, “You’re so bad” versus “That’s a bad act” can make a big difference.

Tell us about the test case of children learning Chinese. Are we fooling ourselves into thinking we’re getting educated using Rosetta Stone or online classes?

[Laughs] No, you’re not wasting your time. The Patricia Kuhl study was about learning the sounds and the idea that all babies are born citizens of the world. They can hear all the sounds of every language. But as an adult, if I hear Chinese, I can’t hear the intonations. Similarly, someone from Japan can’t hear “r’s” and “l’s” that easily.

Why is that? While we’re born citizens of the world, by the end of the first year we have to start honing in on our native language. Our brain wants to focus on what’s important so it starts removing the ability to hear other sounds.

Kuhl looked at American children and had them exposed to Chinese speakers in a lab. One group would hear the sounds of the language from actual Chinese. The other group heard the same thing but on video.

What she found was that the children exposed to the real, live, human interaction were able to get those sounds, whereas those children exposed to the video exemplar were no different from children who hadn’t heard any Chinese at all. In other words you need that social interaction for language to stick in your brain.

How does this relate to Rosetta Stone? You can still absolutely learn language, and your ability to hear tones doesn’t end at the age of one. My children are learning much later. What it does mean is the earlier the better.

I wrote a story about Mark Zuckerberg’s attempt to learn Chinese. Zuckerberg is a genius, and his attempt is laudable. But though he did manage to learn Chinese, it’s been described as sixth-grade level, with rocks in his mouth. He could grunt his way through learning the words, but he couldn’t hear the tones well because he had passed that critical period.

You’re spearheading the Thirty Million Words initiative. Tell us about its mission.

This book is part of our larger initiative of trying to get this message out about the power of language. What we are at the most fundamental level is a research program. I believe that science can be the basis of social change. There are so many programs that feel good but don’t have the impact we want to have. Ours is an evidence-based program that has been demonstrated to work.

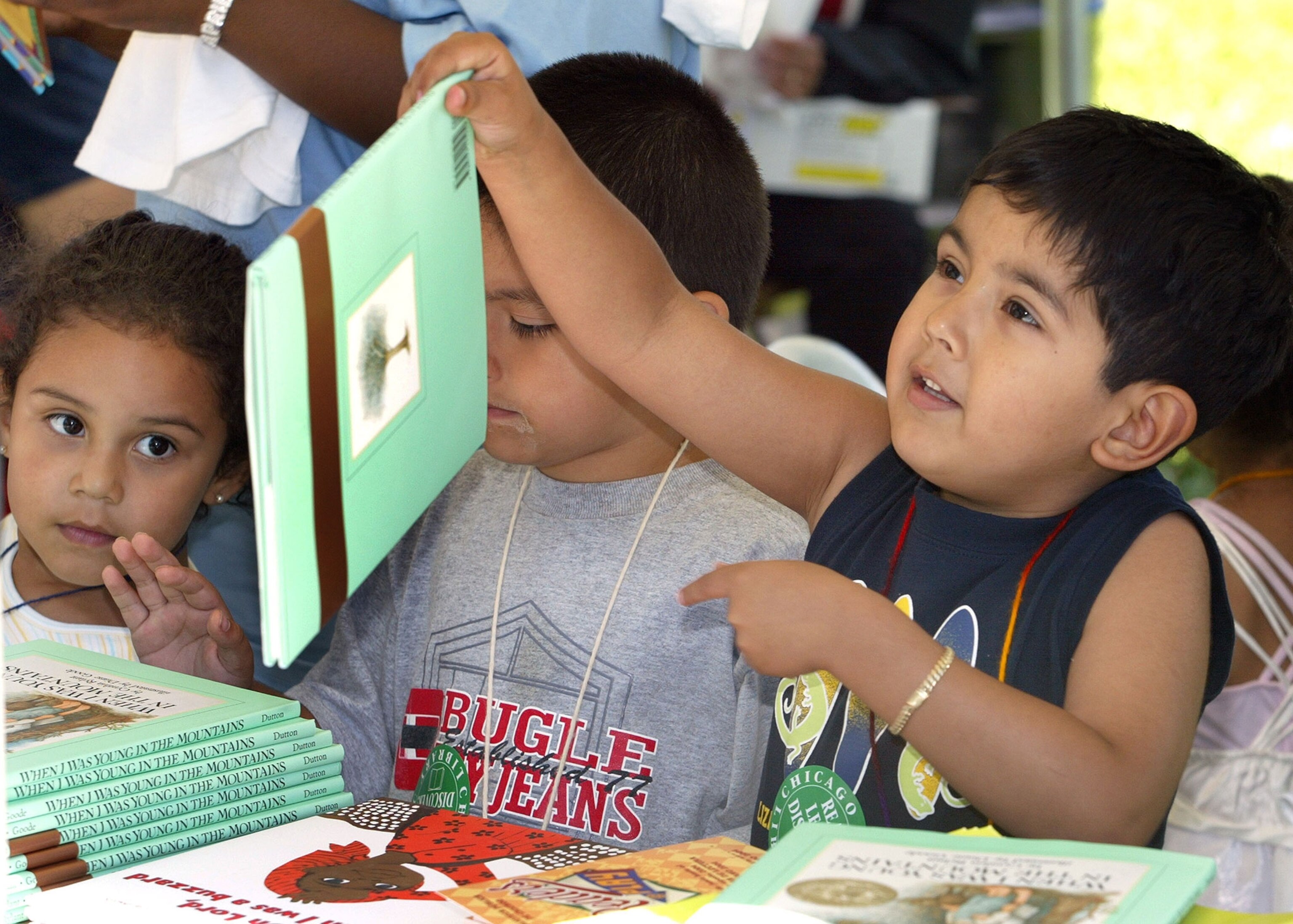

One of our major programs is in partnership with the city of Chicago, with their early Head Start program. We’re working with 200 families from low-income backgrounds. We go into the home with a 12-week program, share the translation of the science and strategies to enrich their children’s learning environment. What’s cool is, we’re starting with children at the age of 13 months and following them up to Kindergarten, to demonstrate how the power of parent talk can impact school readiness.

Are you saying that the solution to society’s ills really could lie in something as simple as exposing infants to 30 million words? If so, why aren’t our governments pouring money into programs that will achieve this?

In order for this to happen, it’s not as simple as saying to parents, “Go talk to your kids!” It’s about understanding that we need to invest in scientifically based programs, which invest in parents so they can invest in kids. Parents have to be the heart of every social program that is trying to close the achievement gap in the early years and beyond.

At the most fundamental level, it’s how babies’ brains grow. We need to understand the brain science so we can do right by these families and children.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.