Why Is the Man Who Predicted Climate Change Forgotten?

Alexander von Humboldt isn’t a household name today, but ecologists and nature writers remain rooted in his vision of nature, says author.

In his time, the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt was an icon, as famous as Darwin or Goethe.

But the global dominance of Anglo-Saxon culture, the increasing specialization of science, and anti-German sentiment arising from two world wars elbowed him into the shadows.

German-born Andrea Wulf, author of The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World, has made it her mission to put a new shine on his reputation—and show why he still has much to teach us.

Talking from her home in London, she explains why it was important to experience the pain of climbing Ecuador’s highest volcano in Humboldt’s footsteps; why without Humboldt there would have been no Darwin; and how today’s environmental writers are indebted to this great German, even if they don’t know it.

Alexander von Humboldt has been largely forgotten in the English-speaking world. Yet he was a towering figure in his own age. Why has he slipped between the cracks of history?

I think there are several reasons. He was the last of the great polymaths who lived at a time when you could hold all the world’s knowledge in your head. As science became specialized, people like Humboldt got pushed to the boundaries.

The other thing, which is probably more important, is that he remained famous in the English-speaking world until World War I, when there was a lot of anti-German sentiment. In Cleveland, in 1859, they celebrated Humboldt’s centennial. But with the outbreak of war, they burned all the German books in the library. And he has never really recovered.

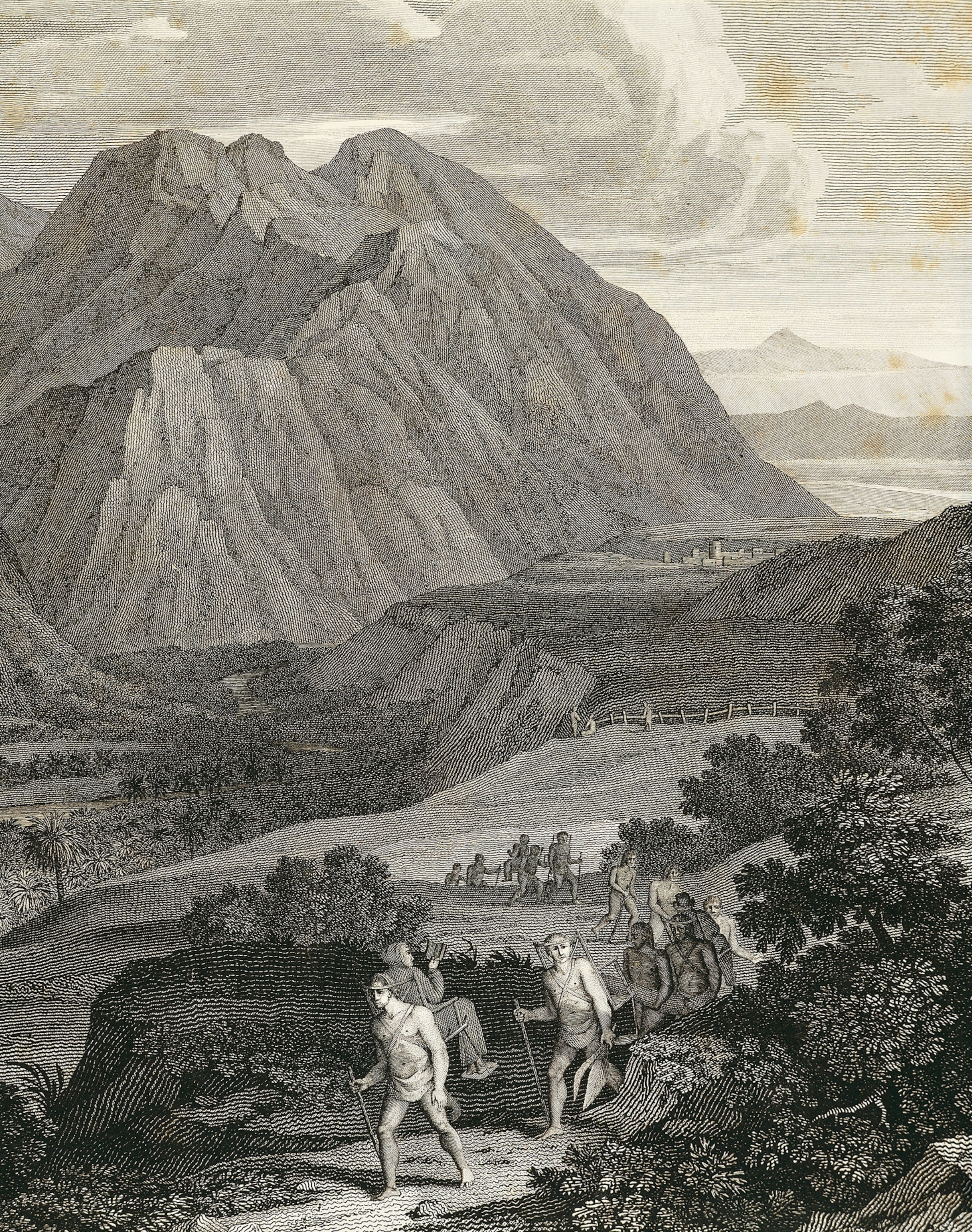

You begin the book with Humboldt’s ascent of Chimborazo, in the Andes. Set the scene for us—and describe your own journey to the volcano.

Humboldt crossed the Andes from the north all the way down to Lima, 2,500 miles away. Along that way, he climbed every accessible volcano. The big one was Chimborazo. At almost 21,000 feet (6,400 meters), it was believed to be the highest mountain in the world.

They have terrible shoes and clothing. It’s snowing and freezing cold. He has an injured foot from a previous climb, his feet are bleeding because the soles of his shoes have been shredded on the jagged rocks, and all the time the peak of Chimborazo is covered in fog.

Then suddenly the fog lifts and they see this snowcapped peak against the blue sky. They also see this huge crevasse in front of them. There’s no way to the top, so they stop there, at around 19,400 feet, about 1,000 feet below the peak. This is still the world record. No one has ever climbed that high. Not even air balloons have been that high. So he’s literally standing on top of the world.

Simon Bolivar says it was Humboldt, with his pen, who awakened Latin America.Andrea Wulf

And it’s that moment when his new vision of nature clarifies, when everything he has seen during his travels falls into place. The journey from Quito, about a hundred miles (60 kilometers) away, up Chimborazo, is like a botanical journey from the Equator to the Poles, from tropical plants in the valley to lichen at the snow line. It’s like a journey across the world, and he realizes that a lot of the plants he’s seeing on that journey he has seen before, in the Swiss Alps or the Pyrenees.

And it’s at this moment that he realizes nature is this global force, with corresponding climate and vegetation zones. On his descent, in the foothills of the Andes, he does his first sketch of what became the Unity of Nature series.

I need to see the landscapes I’m describing. So I went to Venezuela and paddled along the Orinoco, and I went to the Andes. On Antisana, we found the hut in which Humboldt had slept in 1802! I only went up to 16,400 feet on Chimborazo, but the air was so thin, and the climb so hard, that with every step my admiration for Humboldt grew. You have to feel the pain to realize what he achieved. [Laughs]

He traveled extensively throughout the Americas—tell us a bit more about his other adventures and how he influenced South American history.

He left Europe in June 1799 for what became a five-year exploration of Latin America. The important thing about Humboldt is not so much that he’s a discoverer—he’s a connector, who compares and connects things. For example, in Venezuela, when he sees the effects of monoculture and deforestation, he talks about harmful, human-induced climate change.

Then he goes down the Orinoco and surrounding river networks, paddling for 1,400 miles and 75 days deep in the rain forest, where very few white men had been. It’s pure adventure—they’re starving and encountering jaguars and crocodiles. Later he travels through the Andes, which is the harshest landscape you can imagine.

They leave Bogotá in September, which is a really terrible time. They battle snow and rain and storms, while schlepping their collections and instruments all the way to Lima. On the way, Humboldt discovers the magnetic equator, collects Aztec manuscripts, and makes drawings of Inca monuments. He’s not just interested in nature. He brings back to Europe this extraordinary portrait of these ancient Latin American civilizations, which were really sophisticated, with rich languages and architecture. That was very new at that time. Most Europeans basically regarded indigenous people as savages.

Later, in Paris, he meets Simon Bolivar, who is basically trying to get over the death of his wife with the help of gambling, sex, and alcohol. They talk about the liberation of the colonies, and Bolivar later says that it was Humboldt, with his pen, who awakened Latin America.

Did your own German background inspire you to write this book?

I was born in India, and then grew up in Germany. Because I’m German, I obviously had heard of Alexander von Humboldt in history lessons. Funnily enough, my very first essay at university in Hamburg was about him. In the books I later wrote about the history of science or the history of nature, Humboldt kept popping up.

Darwin would not have been Darwin without Humboldt.Andrea Wulf

When I wrote The Founding Gardeners, I had a whole chapter about Humboldt’s visit to Washington, D.C., in 1804 when he met Jefferson and Madison. It was deleted in the final edit, but I took that chapter, put it aside and thought, I’m going to write a book about this one day.

I had to write a few books before I dared tackle him, though, because he roams across so many disciplines, from astronomy to geology, botany to meteorology. My mission is to try to make him famous again—and restore him to his rightful place in the pantheon of nature and science. [Laughs]

He was amazingly prescient, even predicting exploration of space—talk about some of the ways he anticipated our own age.

Because he makes connections, he was able to see things other people didn’t see, like human-induced climate change. He saw what happened in European colonies where cash crops and monoculture destroyed the forests, creating soil erosion. He was the first to explain the importance of the forest to the ecosystem.

But he was curious about everything, not only nature. He was obsessed with the telegraph and would have loved the Internet! [Laughs]

As regards space, he said that if our future continues with this level of technological progress, one day we might go to other stars. He wasn’t very optimistic, though. He thought that if we ever did go to other planets, we would probably take our bad habits of vice, greed, and destruction with us and destroy them too. It’s pretty amazing to say that in the mid-1800s!

What was his relationship with the other great naturalist of the age, Charles Darwin?

Darwin would not have been Darwin without Humboldt. Darwin himself said he would have never boarded the Beagle without Humboldt, and if he’d not boarded the Beagle, he’d never have written Origin Of Species. As a young man he read Humboldt’s books, in particular the Personal Narrative, which is part travelogue and part scientific treatise. Darwin absolutely fell in love with Humboldt’s descriptions and wanted to go and see South America himself. He saw this new world through the lens of Humboldt’s writings.

The copy of Personal Narrative that Darwin owned and took on the Beagle, which amazingly is now at Cambridge University Library, is filled with hundreds of underlines and scribbles in the margin. Reading those is like listening to Darwin talk to Humboldt.

Then there is this fabulous moment in 1842 when they actually meet. Humboldt is in London. He is by then in his 70s and accustomed to being the center of attention. He also has a tendency to talk a lot and ramble, so Darwin was completely disappointed when he actually met the man. Origin Of Species was then published four months after Humboldt dies.

Humboldt had a complex relationship with the United States, didn’t he? Describe the two sides of that coin.

He made a huge detour on the way back from Latin America to Europe because he wanted to see Jefferson and Madison. He was a great fan of the American Revolution and the revolutionaries. He said, I’ve seen the splendors of nature, now I want to see a people who are ruled by liberty.

So he stops in D.C. and meets Jefferson. They get on really well and continue to correspond until Jefferson dies. Humboldt always sends his latest book to Jefferson. But throughout his life he remains very critical of slavery.

On the one hand, he says I’m half an American, because he adores America. But he can’t understand how someone like Jefferson can reconcile his belief in liberty and equality with slavery. He’s very critical in a very public way. He writes about it in his books, but in the American translations they leave out all of Humboldt’s criticism of slavery.

He adores America but can’t understand how Jefferson can reconcile his belief in liberty and equality with slavery.Andrea Wulf

Humboldt gets absolutely furious and writes this long letter, which is then published in the American newspapers, basically saying: This is not my book—the most important part of the book is missing, which is my criticism of slavery.

Why should we care about Humboldt today?

First, his story explains why we understand nature the way we understand it today. Humboldt gave us our concept of nature. He wanted to make people fall in love with nature and feel a sense of wonder. Humboldt’s insight that we can only truly understand nature by feeling nature is incredibly important today.

He created a new style of writing, which became important for people like John Muir, who takes the baton of nature writing from Humboldt. Environmentalists, ecologists and nature writers today remain firmly rooted in Humboldt’s vision of nature as a web of life, although many of them may not have heard of him.

His idea of the free exchange of knowledge and fostering communication across different disciplines is still a pillar of science.

Perhaps most important, as scientists try to understand and predict the global consequences of climate change, Humboldt’s interdisciplinary methods—his insight that nature is a global force and the way he links social, economic, and political issues with environmental problems—is still incredibly topical.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.