Custer to Casinos: One Native American Family’s Story

Individualism is anathema in a tight, egalitarian community like the Acoma Pueblo, says author.

During a train ride across America as a child, Peter Nabokov saw a group of Native Americans through the window—and a light bulb went on in his head.

Nothing in his Russian émigré background suggested that this epiphany would lead any further than the usual games of cowboys and Indians and a plastic tomahawk.

His father, Nicolas, was a composer. His cousin, Vladimir Nabokov, a lepidopterist and the author of Lolita, was one of the 20th century’s most controversial novelists.

But the child at the train window went on to live and work with numerous tribes, including the Crow and Lakota; write eight books; and serve today as Professor of American Indian Studies and World Arts at the University of California, Los Angeles.

His latest book, How The World Moves: The Odyssey Of An American Indian Family, tells the powerful story of an Acoma Pueblo family from New Mexico as they battle to preserve their culture across three generations.

Speaking from his home in Playa del Rey, California, Nabokov describes how Hitler regarded the Sioux as Aryans; why he thinks the Acoma Origin Myth ranks with the Bible and the Koran as one of the world’s great texts; and why casinos are a godsend for Native Americans.

You’ve written a number of books on Native American culture, and you’ve lived among the Navajo and Lakota Indians. What drew you to this field?

I’ve sought the answer to that question many times. It’s my “Rosebud,” to cite Citizen Kane. It’s a little bit of a mystery, but the earliest I can remember that I was aware of Native Americans on this continent was when I was six, on a train with my mother, and we were going through the Wisconsin Dells, which is a gathering place for American Indians of many tribes in the Great Lakes region.

It was partly because he took “the white man’s road” that he came into bad odor with his people.Peter Nabokov

She pointed out the train window and said, “Those are Indians, they were here first.” Something about that idea knocked me out, and I’ve been trying to explore what that simple statement means pretty much all my life.

This book is a multigenerational story about Edward Hunt and his descendants. Give us a brief narrative arc.

This gentleman was born in 1861, as best we can tell. He chose the middle of February as the month somewhat arbitrarily, because dates were uncertain where he was born on top of a rocky mesa in western New Mexico. He died in 1948.

That lifespan, from the onset of the Civil War to three years after World War II, in which one of his boys participated, was a pretty eventful time in American history as well as in Indian-White relations.

For various reasons he ended up acquiring a lot of knowledge and a new religion, which was Christianity. He also acquired the status of something of an outcast, because he brought back to his community ideas and influences that were not necessarily welcome. He and his family led a peripatetic life, bouncing off of American Indian government policy towards American Indians, which vacillated every 20 years.

The book is set among the Acoma Pueblo of New Mexico, one of the most remote and conservative Native American tribes in the area. Tell us about them.

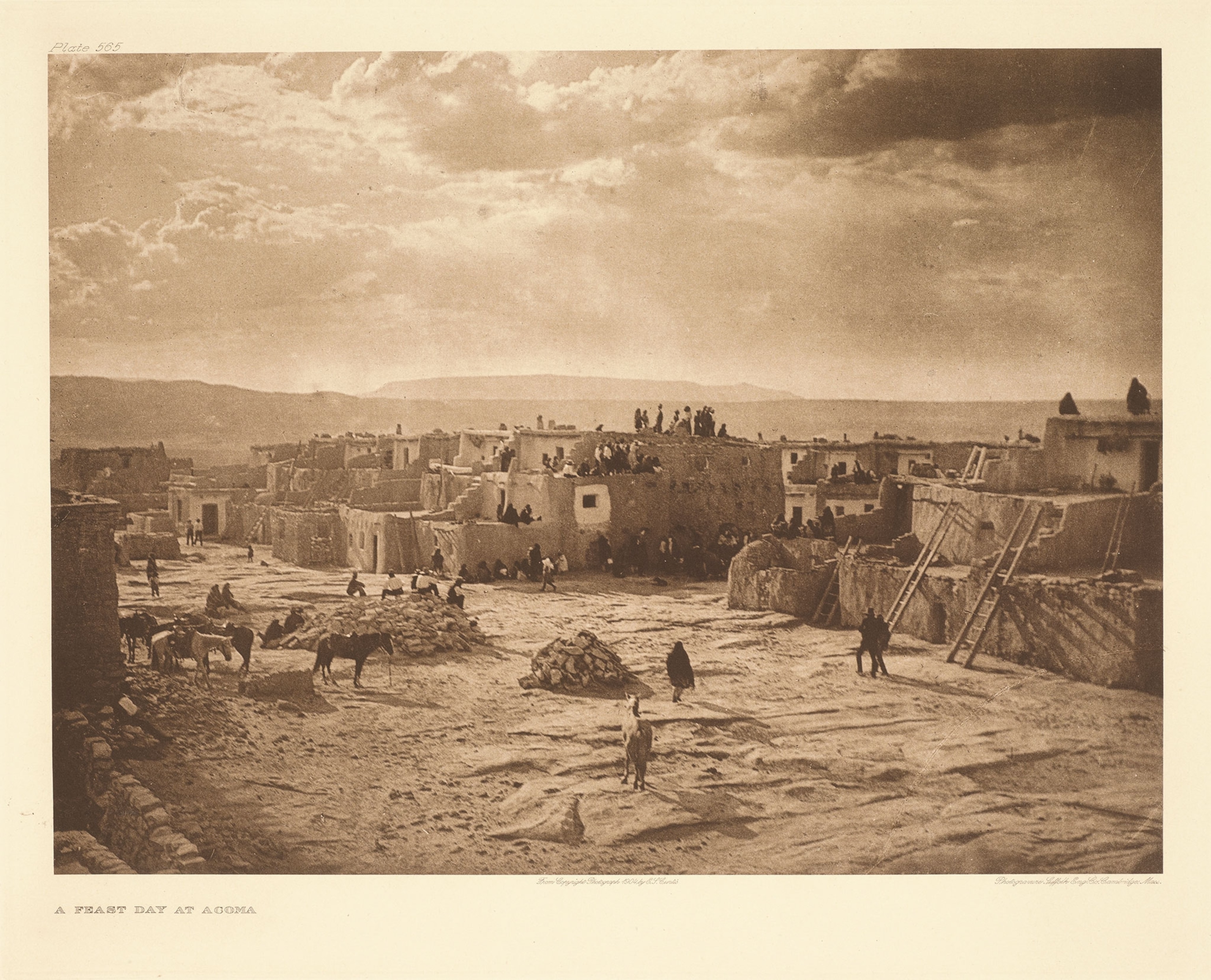

These were some of the oldest continuously occupied communities in North America. This gave me an opportunity to tell about the archaeology of the region; the arrival of the Spanish and its impact; the great 1680 revolt of the Pueblo Indians, which was still remembered by his home community.

This story deserves inclusion alongside the Bible, the Koran, and all the other great texts of world literature.Peter Nabokov

Stories were told to him about that dramatic and painful episode in the life of their culture, and the coming of Euro-Americans in the 1840s, first to his mesa, eventually taking over the Southwest and introducing a new political regime. There were layers of regimes: the Spanish regime and the American regime, on top of what was already a very complex socio-political foundation. So you have an impasto of cultures in the Southwest, which exist to this day in sometimes fraught, sometimes amenable relationships, but always tremendously interesting.

How did you find this story?

I was interested in doing a book on American Indian architecture. For that book I wanted to look at every possible American Indian creation story I could find, because so often lurking in them are accounts of the culture’s very first house.

This is a familiar circumstance the world over, whether in Africa, Latin America, India, or North America. I found this castaway government publication called The Origin Myth of Acoma Pueblo, published anonymously. It was told by a group of Indians who appeared in Washington, D.C., in 1927—that’s all it said. But with a little sleuthing I was able to locate the name of the author at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Anthropological Archives in D.C. and a phone number.

I called it, and there was an old man at the other end who was that last surviving son of the 12 children of Edward Hunt. He said, “Yeah, that was my father. I was there in Washington in 1927. Sure, you can come out.” So I immediately got a ticket and flew out to New Mexico.

Edward Hunt was caught between cultures and eventually banished from his tribe for taking “the white man’s road”—specifically, revealing secret initiation ceremonies to the outside world. Describe his conflicted world and the ordeals he faced as a result.

The initiatory stories are what he patched together for the origin myth that he told to the then director of the Smithsonian’s Bureau of American Ethnology, Matthew Sterling. He was the one who was on deck, so to speak, when Edward Hunt showed up with his family and began to recite this great story.

Those narratives are sometimes described as “original instruction.” By that, it means they’re not only entertaining stories. More importantly, to the tribe, they’re formulas for how to conduct various rituals expected to have practical efficacy in the world, like healing rituals or rituals for putting a painful past behind you. It was partly because he took “the white man’s road” that he came into bad odor with his people.

That meant a number of things. For one thing, although he tried to hide it, it meant a connection with Christianity. At government boarding school, Edward Hunt became what you might call a closet Protestant.

The other thing he brought was a notion of individualism, which is anathema in a tightly knit, egalitarian community like Acoma. He also brought in the capitalist ethic.

Most grievous for the community was his reluctance to allow his sons to be initiated into the kivas (sacred chambers) and become participants in the esoteric aspects of Pueblo religion. Remember, these communities are not large demographically. They need all the recruits they can get to fill a multitude of roles both secular and sacred.

You’re a white man yourself. How did the Acoma tribe regard this project?

They didn’t know about it. [Laughs] There was some concern about the republication of the Acoma’s Origin Myth. When it was published in 1942 by the Bureau of American Ethnology, it sat under-appreciated for a number of years. Later on, it appeared in excerpted form in anthologies. With the coming of the Internet, various people put it out in the public domain, including the pictures, the kachina masks, the maps and depictions of sacred altars.

I thought this publication of the Origin Myth deserved a second, more dignified shot. So I didn’t allow any pictures of the sacred altars or kachina masks to be republished, just the text. I feel this story deserves inclusion alongside the Bible, the Koran, and all the other great texts of world literature.

In the 1920s the Hunt family ended up joining a Wild West show and travelling to Germany. Hitler would later declare the Sioux Indians “Ayrans.” What’s going on here?

There was a fascination for American Indians in Europe generally, which became particularly acute in Germany. A variety of explanations have been given. One is that it represented a return to indigenous roots in Germany after the humiliation of World War I.

Another is that here is a “race” of warriors. The preferred tribe was never the Pueblo Indians of the Southwest, which are generally peace-professing cultures, more concerned with growing crops than cutting off scalps.

The Indians preferred by Europe to this very day are the Plains Indians, the horseback riding Indians who had to compete against each other for territory. Once the U.S. military comes in and threatens their autonomy over the Plains, they confront the cavalry, which leads to all kinds of great stories. These were immediately taken up by the Wild West shows, which became beloved in Germany and the rest of Central Europe.

One of the most fascinating characters in the book is Solomon Bibo, who became known as the “Jewish Indian chief.” Tell us about him.

Bibo was one of five brothers who came over from Prussia in the 1850s to settle in New Mexico, along with other Jews who became established merchants throughout the Southwest. Jews would come from Prussia to New York, apprentice themselves in the big trading firms and then be sent west to establish trading houses in Las Vegas, Albuquerque, or Santa Fe.

The five Bibo brothers ultimately all came to New Mexico. Solomon Bibo staked out the area of Grants, New Mexico, where he became acquainted with elders of the Acoma pueblo. He ended up falling in love with the highborn daughter of an aristocratic family, named Juana, and marrying her. That gave him family connections to a very important Acoma clan, the Antelope Clan. He eventually became something of a culture broker, the owner of vast herds of sheep and a financial force in the area, with some suspicious dealings, to be sure.

Ultimately, the tribe voted him in as a governor, the figure dealing for the Pueblo with the outside world, like the Secretary of State. It was that office of governor that was translated into “Jewish Indian Chief” by people back East. Yiddish theater even promoted that image and created a story line together with music and lyrics.

Despite their conservatism, the Acoma, like many other tribes, have ended up opening a casino. Isn’t that the opposite of everything they have sought to preserve?

Those of us who teach American Indian studies have to constantly remind outsiders, with their sometimes highfalutin attitudes, of a couple of things. One, these are sovereign nations. Within the reservations, they control, administer, and police; they have the right to do whatever they want.

Two, for the most part, the proceeds of these operations have gone into things like senior centers or meals on wheels, buying land that has been in dispute, or setting up training centers for their young in Internet technology.

It also lifts the tax burden on other American citizens, who would otherwise have to pay for programs to help indigenous peoples. So I’m very impatient with this haughty, almost imperialistic, attitude toward Indian casinos.

Why is the Huntses’ story important—not just to Native American culture but for the rest of us?

There’s something inspirational about the efforts of this family to survive under arduous circumstances for a century or two while retaining their roots and their basic humanity and sense of humor.

For the reader, it provides an opportunity to personalize more than a century of Indian-white relations and American history. I call it an odyssey because Wilbert Hunt, the last of his family, ends up living back at the Pueblo at Acoma. When asked why he had returned he said, “ I want to see Mount Taylor in the morning.”

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.