Author Unlocks the Realities of a Mythic Arctic Sea Route

The Northwest Passage is known for Northern Lights and polar bears—but also resource grabs that harm the environment and indigenous cultures.

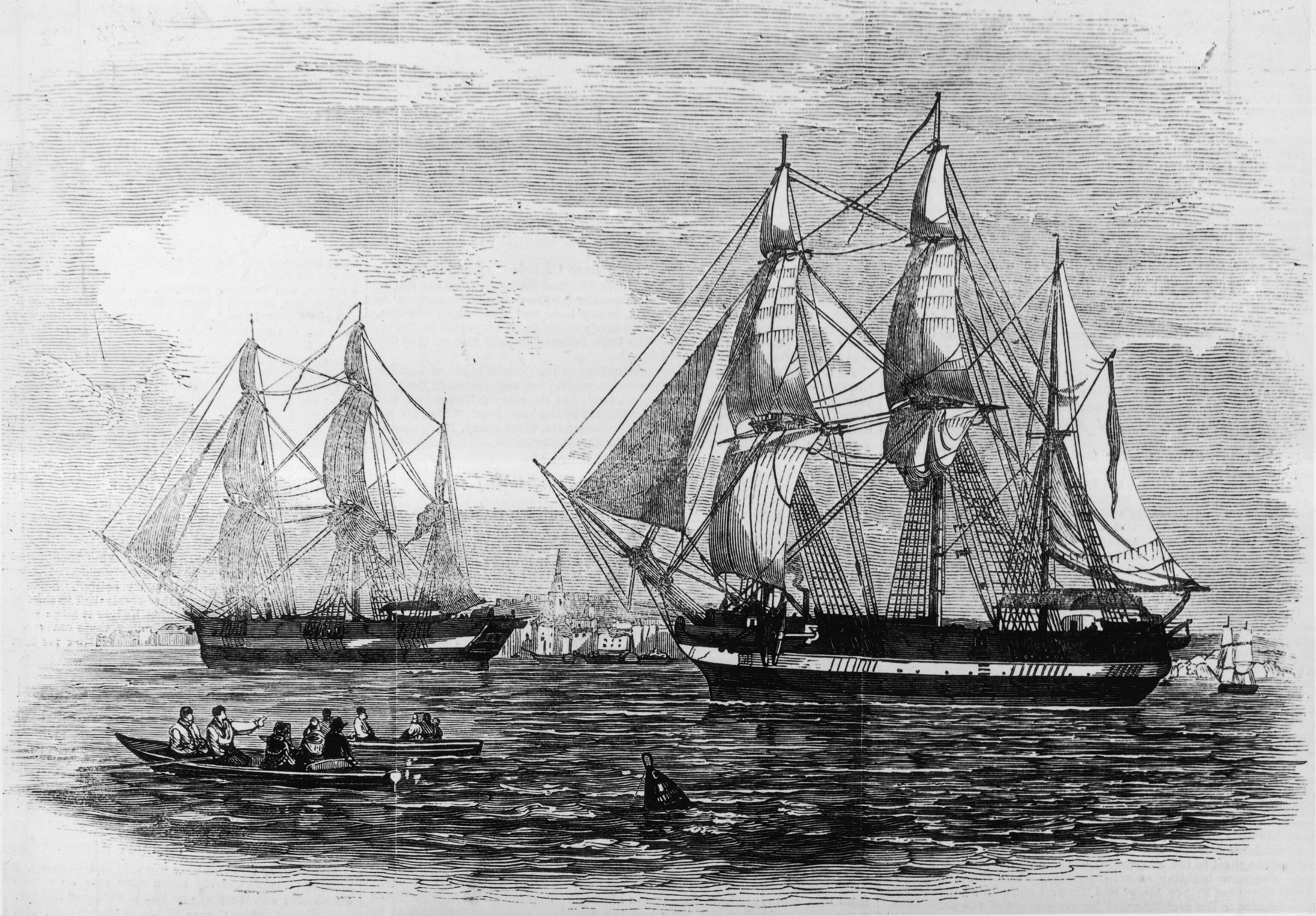

For centuries, it was a chimera on the horizon of European dreams: a mythic sea-route through the Arctic that could link the riches of Asia to Europe. But even after the Northwest Passage had been charted, unless you had a nuclear-powered icebreaker, it remained firmly closed. Now, this mythic land and its resources is being unlocked by global warming.

So when Canadian author Kathleen Winter was invited on a scientific expedition to explore the passage, she jumped at the chance. In Boundless: Tracing Land and Dream in a New Northwest Passage, she explores the new realities of the North where Inuit are used as “human flagpoles” and the world’s superpowers are poised to make a land grab for the Arctic’s resources.

Speaking from her home in Montreal, she describes how objects dropped hundreds of years ago still dot the landscape; what a Greenland woman sang to a polar bear; and how she almost became trapped in the ice.

You describe the Northwest Passage as a land of fables and the channel of dreams. Why is it so mythical and what drew you to its romance?

It has always been a dual-natured fascination. Colonial governments intentionally capitalized on the romance of it, while looking to finance exploration of the passage to get the riches from a trade route to Asia. And it is a fabled land of dreams because it has been unattainable and closed in ice, which, as a liminal substance, reflects all light.

This is the place of the Northern Lights, the polar bear, things that seem mythical in a world where the everyday has less and less romance and mystery. There is a psychological beauty to being in a place of 24-hour light; a place also of 24-hour darkness. What does that do to the inside of a person? I was fascinated with the idea of going there and then, serendipitously, one morning I received an invitation. How could I say no?

As you are flying over Greenland, the pilot says about the landscape below, “A whole lot of nothing,” but you discover the opposite. What was beyond the apparent “nothingness” of the North?

Two things. One is the human imprint, the things that people have left behind. Nothing gets picked up by municipal works people. There are buttons and rusty kettles and bits of wood from ships’ crates. Some are from 10 or 20 years ago, some are from hundreds of years ago.

It is a fabled land of dreams because it has been unattainable and closed in ice, which, as a liminal substance, reflects all light.Kathleen Winter

Next to those things left behind are the archeological remnants of the indigenous people that go back millennia. It is all simultaneously on the ground, as if it had been dropped just this morning.

It is like a three-dimensional living history book in which the stories, words and parts of speech are things instead of words. That in itself is fascinating. But there’s also a mystery to each thing. Was this peg left by an Inuit person drying a caribou skin or was it left by a stranded, white explorer? There are so many possible dialogs about these artifacts. It’s a fascinating place to discover.

Then there are the animals, the land, the stones, the air, and the light. Those natural things had a powerful effect on me that I could only begin to put into words several years after I was there. How do I explain what the land said to me?

Describe the lamp lighting ceremony on your first night arriving in the North.

The lamp is made of stone with seal oil in it and a wick made out of plant material. The ritual was performed when we arrived in the North and as it was lit, we were told how light and flame are used in the North. The flame was so tiny and soft, yet the light it gave off was powerful. I could see the whole room, and everybody in the room. You could probably read by it and it gave off heat. It is such an ancient and non-technological thing. Just a flame floating in molten fat. But it looks like it is floating on water, and we were welcomed to the North by it.

Aaju is a Greenlandic Inuk woman, who now lives on Baffin Island, in Canada. Tell us why she prefers life in Canada even though the economy is better and more prosperous in Greenland.

We landed in Greenland first and saw beautifully painted and built houses. When we got to Canada, the houses are makeshift, inadequate. The whole living situation is fraught with social problems. A lot of the people on board the ship, myself included, asked Aaju what was going on?

She explained that Greenland, “looks nicer, but the food security is completely based on Danish and Southern principles. It’s commercialized; you buy and sell your catch. Whereas, in the north of Canada, we share it.” Then she added, “I would never go back to Greenland.”

Aaju went down on one knee on the stones and looked straight at the bear, as he loped towards us and then began to sing. She was not afraid.Kathleen Winter

I could understand her feelings. If you go into a supermarket, one of the co-op shops in the far north of Canada, you will not see sugar-filled, fake food at exorbitant prices that nobody can afford.

People like Aaju also practice another layer of food acquisition that is ancient and sustaining. It is also imperiled and threatened by modern practices of buying and selling, rather than sharing. This might not be as visible to tourists passing through, but Aaju said she wouldn’t exchange her freedom to share food she caught with her community for the Greenland model.

Let’s talk about the escalating resource grab going on in the Arctic—particularly with regard to oil.

Everywhere we went there was a military presence. Everybody thinks the Coast Guard is there to rescue grounded vessels, but it has been commandeered by geologists working for big oil companies and consortia of government and business, who are mapping the waters of the Arctic for oil exploration.

It’s not a new thing, either. The Canadian government physically moved Inuit people from more southerly communities and took them away from their families to put them farther north, as part of what was known as “human flagpoles,” to assert sovereignty. That is a huge part of the Canadian government’s agenda.

The recent discovery of the ships from Franklin’s expedition was, in my opinion, part of the Canadian government’s attempt to twin this romantic tragedy with an urge to take possession of the resources in the North.

You visit the graves of the first men to die on the doomed Franklin expedition and discover someone else lives on that island now. Tells us about Aaju and the Polar Bear.

Beechey Island is where three men from the doomed Franklin expedition were buried. It’s a desolate place of mostly limestone rubble, with little vegetation. I had a feeling of great sadness when I looked at the gravestones.

We had arrived on Zodiacs, which transported us from the ship, and as we were standing there we heard crackling on the radio from the edge of our gun perimeter. Aaju and other members of the expedition crew formed a gun perimeter around us when we explored uninhabited places, as a lookout for polar bears. The watchman told us to get back to the Zodiacs because there was a male polar bear heading for us.

Polar bears look as if they’re loping slowly, but they are covering a great distance. He was only about two kilometers away. We were told not to hang back and try to watch, but as a writer I waited while the first two boats left.

The first thing you do when you go aboard a ship is have lifeboat drill, which is a bit like a fire drill at school. But this time it was real.Kathleen Winter

Aaju went down on one knee on the stones and looked straight at the bear, as he loped towards us and then began to sing. She was not afraid. Her gun was lowered. She just stared the bear in the face and sang. Afterward I asked Aaju what she was singing to the bear.

“I was telling the bear that we respect that this is his place, not ours,” she told me. “That we mean him no harm; and to please know that we are leaving and that he has sovereignty over this place.”

You write, “In the Arctic, we do not own or contain individual thought, but rather move in a living element that contains us.” Can you unpack this sentence for us?

There were times when we could get away from the other passengers and walk on the land and be one with the land. It’s hard to talk about this in a way that people don’t just roll their eyes. All I can say is that I felt a distinct sensation that the boundary between ego and earth was dissolving in my consciousness.

I have heard environmentalists and native elders tell me we are connected to the earth. We hear things like that all the time. It was in the North that I experienced what that means in a deep and visceral way.

You have an abrupt end to your trip. Tell us what happened and how you were rescued.

It was the second to last day of our journey. We were about to sit down to dinner when there was a horrendous grinding sound coupled with a shaking and scraping of the ship. It took the best part of a minute for the ship to stop. When we stopped we were leaning at a six-degree angle after becoming grounded on some rocks. The first thing you do when you go aboard a ship is have lifeboat drill, which is a bit like a fire drill at school. But this time it was real.

The alarm went clang clang clang, the lifeboats were lowered into the water and we were all told to put on our lifejackets. It was a real crisis. After about an hour the captain announced that the ship was stable, and we were able to return on board. But we were there for three days before the Coast Guard could come and rescue us. Imagine if we had been on lifeboats or a nearby island for three days. But, unlike Franklin, we were lucky and had a fairly nice time being shipwrecked!

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.