A Race to Save Ancient Human Secrets in Borneo

Archaeologists enlist UNESCO's help to protect prehistoric sites threatened by limestone quarrying.

If you wanted to create a new UNESCO World Heritage Site, you might well look to the limestone landscape, or karst, on the Sangkulirang Peninsula in eastern Borneo. There, in the Indonesian province of East Kalimantan, you could cite the abundance of human and natural riches to justify your proposal.

For seven years, archaeologist Francois-Xavier Ricaut, from the University of Toulouse, and his French-Indonesian team, MAFBO (Mission Archéologique Franco-Indonésienne à Bornéo), have been excavating three sites in the Sangkulirang-Mangkalihat karst, which spans 3.7 million acres (1.5 million hectares).

In the karst, thick tropical forest shrouds weathered limestone spires, making it hard to get around, let alone do science. As a result, Ricaut says, “hardly any archaeological work has been done in this karst—we’re just beginning.”

After dogged sleuthing, Ricaut and his colleagues have found bones and charcoal that date back 35,000 years, the earliest such evidence of human occupation yet found in Kalimantan.

“These early remains are exciting,” he says, “because Kalimantan has for a long time been excluded from the human evolution and dispersal story.”

UNESCO seems to recognize the natural and cultural values of this landscape. The organization has placed the karst on its tentative list of sites to protect and has shown interest in sending a team out to see the region.

But Ricaut worries that recent scientific finds, and UNESCO interest, may be coming too late. Rapid expansion of plantations of oil palm, and illegal logging, have put pressure on the area, and now industrial companies are poised to mine the region’s limestone, the main raw material for making cement. Forest fires—ones now raging in Kalimantan were likely intentionally lit to clear land—compound losses of wildlife and habitat.

It’s anyone’s guess what might disappear. The “hobbit,” Homo floresiensis, discovered a decade ago in a karst cave on Flores, Indonesia, continues to rouse scientific curiosity and debate. It is thought that this miniature hominin lived as recently as 12,000 years ago alongside modern humans.

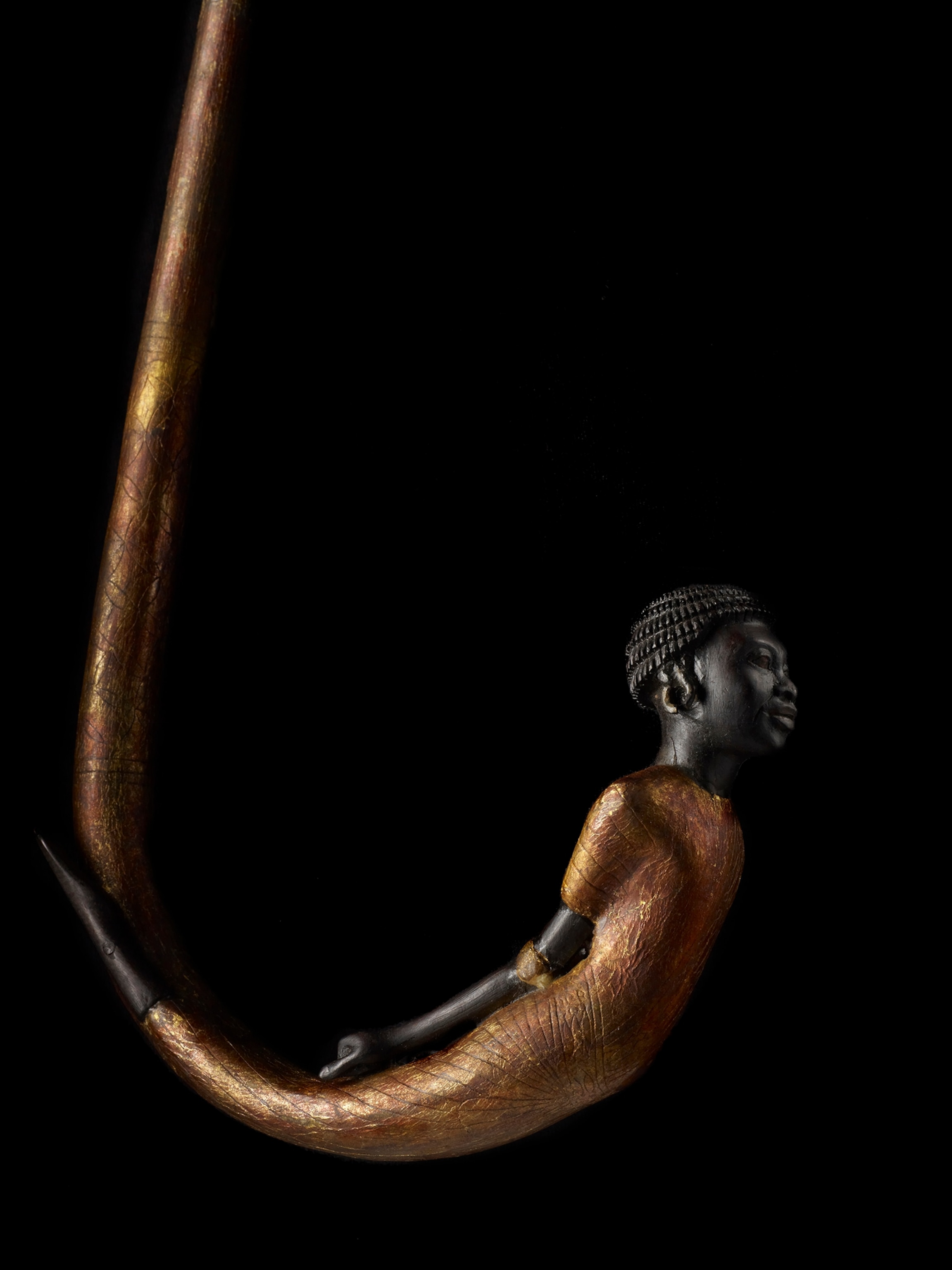

The French-Indonesian MAFBO team is working in the same area where ancient people made impressions of their own hands in cliffside caves 10,000 or more years ago. Along with the old bones they’ve unearthed, Ricaut says they’ve found hundreds of prehistoric rock paintings that show, in orange to brown hematite pigments, the figures of animals such as tapirs (now extinct on Borneo), banteng (wild cattle), and some creatures unknown to us today.

Blind Fish, Orangutans—And Indigenous People

The wonders of the Sangkulirang-Mangkalihat karst are not limited to the human imprint: Southeast Asia’s limestone hills and valleys have been dubbed “imperiled arks of biodiversity.”

“I was speechless when exploring this karst,” says Rondang Siregar, an Indonesian biologist from the University of Indonesia, in Jakarta. The region is brimming with rare limestone-restricted species.

“I saw blind freshwater fish, rare bats, black- and white-nest swiftlets, and countless other animals," she says. "The karst forest is also a refuge for orangutans fleeing forest fires during El Niño years.”

Matthew Struebig, a tropical ecologist at the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, says the diversity of bat species is greater here than most anywhere else in Southeast Asia. And the sheer number of bats is impressive. “Some Sangkulirang caves support populations of several hundred, if not millions, of individuals.”

In one cave, Struebig says he stumbled across a massive cockroach—a serendipitous discovery that speaks to the range of lifeforms in the karst. “It turned out to be a new species endemic to the cave and one of the largest cockroaches in the world at nearly four inches.”

“Elsewhere in Borneo, such important limestone systems are protected, Struebig says. “It’s sad and surprising that the Sangkulirang karst, which is probably more culturally and environmentally important, is still largely unprotected.”

The region is a refuge too for some 2,000 Lebbo’, the only ethnic group to inhabit this inner part of eastern Borneo. “Similarly to ancient people,” says Antonio Guerreiro, the MAFBO team’s ethnolinguist, “the Lebbo’ shelter and rest in caves when traversing the karst.”

Guerreiro says that the Lebbo’ incorporate elements of the cave paintings into their narratives. “One Lebbo’ myth involves a young shaman and his eight wives, who took possession of the karst territory by marking the caves with stenciled hands”—the very kinds of hands imprinted on cave walls millennia ago.

Without help from these local people, Ricaut says, the MAFBO archaeologists’ work wouldn’t be possible. “Some years, we’ve had 40 Lebbo’ helping us. Apart from sheer manpower, they know the karst and forest, so help locate rock shelters and interpret paintings.”

Cement vs. Heritage

Now, a Chinese company—Anhui Conch Cement Company Limited, which already has a quarry in southern Kalimantan—has obtained authorization to extract limestone in the karst. The permit is set to expire by year’s end if work hasn’t begun by then.

Some 1,500 square miles (3,900 square kilometers) of the karst are protected from exploitation under a “governor decree,” which could be strengthened—or rescinded, with a future change in government.

“The level of threat will depend entirely on where their quarry is sited,” says Tony Whitten, of the group Fauna and Flora International, which has run a conservation program in Indonesia since 1996 and helps protect limestone areas throughout Asia.

Over the years, Whitten himself has strived to raise the profile of karst ecosystems, producing a set of guidelines for extractive industries.

He advises that an environmental impact assessment should precede all quarrying, but “because limestone, like river sand, is a Class 3 mineral—cheap and abundant—in Indonesia, not much attention is given to the impacts of its exploitation.”

Companies can operate unfettered if iconic species like elephants and tigers aren’t present, Whitten says. “Efforts must be made to find small range-restricted species including crabs, spiders and snails”—more cryptic species that play vital roles in the ecosystems they inhabit.

It’s uncertain which, if any, protection standards for biodiversity and cultural property Anhui Conch Cement company upholds. The company didn’t respond to a request for comment about its quarrying plans. But Anhui isn’t a member of the global Cement Sustainability Initiative, which mandates that companies commit to restoring quarried areas.

Other companies have gone ahead with limestone quarrying in fragile habitats in Southeast Asia despite efforts by concerned scientists to have those areas declared off-limits for development.

One group of researchers went so far as to name a new species of snail Charopa lafargei after Lafarge, an international cement company working in Malaysia, in the hope that the name association would encourage the company to spare one limestone hill where the snail is endemic. Lafarge has agreed to spare an area equivalent to 10 baseball fields.

In Malaysia’s Merapoh karst region, biologists set out to find a new creature to help in their bid to stop quarrying by the Singapore cement company ASN Pte Ltd. They found their smoking gun in June 2013—a new species of rock gecko they named Cnemapsis selamatkanmerapoh (the second name meaning “Save Merapoh” in Malay). Quarrying there has been put on hold.

Protection in Perpetuity?

Pak Made Kusumajaya, the head of the National Conservation and Museum Agency, is pushing to have the Sangkulirang-Mangkalihat karst protected as Borneo’s third UNESCO World Heritage Site—the first and only one to harbor mysteries of our prehistory.

“The caves should be awarded world heritage site status so that the traces of human activities they contain can continue to testify to the history of the region’s human migration,” Kusumajaya says. “It is this history of migration that has shaped our culture, beliefs, and traditions.”

“We’ve explored less than 10 percent of the area,” Ricaut says. “The karst is like a labyrinth—so much could be lost to quarrying.”

If UNESCO decides to protect this landscape, will protection come too late? The actions of Indonesian authorities could be decisive.

According to Jaap Jan Vermeulen, a researcher who coauthored with Tony Whitten a World Bank book on limestone biodiversity and cultural heritage, the Sangkulirang-Mangkalihat karst is as crucial to Borneo’s heritage as the existing 3,800-square-mile (9,800 square kilometers) Transboundary Conservation Area (spanning Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo). Noted for its biodiversity, this is the single largest protected area complex in Borneo.

Rock art specialist Pindi Setiawan and archaeologist Bambang Sugiyanto, who have collaborated with the French team for 15 years, extol the karst for a further reason: water. Five major rivers in East Kalimantan intersect in the region.

“The water catchment and storage in this karst is essential to human survival,” Sugiyanto says—“200,000 people who live on the Sangkulirang Peninsula rely on this water.”

If limestone is quarried, the hydrology of the karst and the flow of its remarkably pure underground water could be disrupted. “It’s a rare water source which needs no treatment before it’s piped to the city,” Whitten says. “A bit like Evian in your pipes!”

If the karst can’t be fully protected on the basis of natural and cultural heritage, then perhaps it will be for the water that people in East Kalimantan need to drink.

Follow Katarzyna Nowak on Twitter.