Text by Contributing Editor Laurence Gonzales, Deep Survival

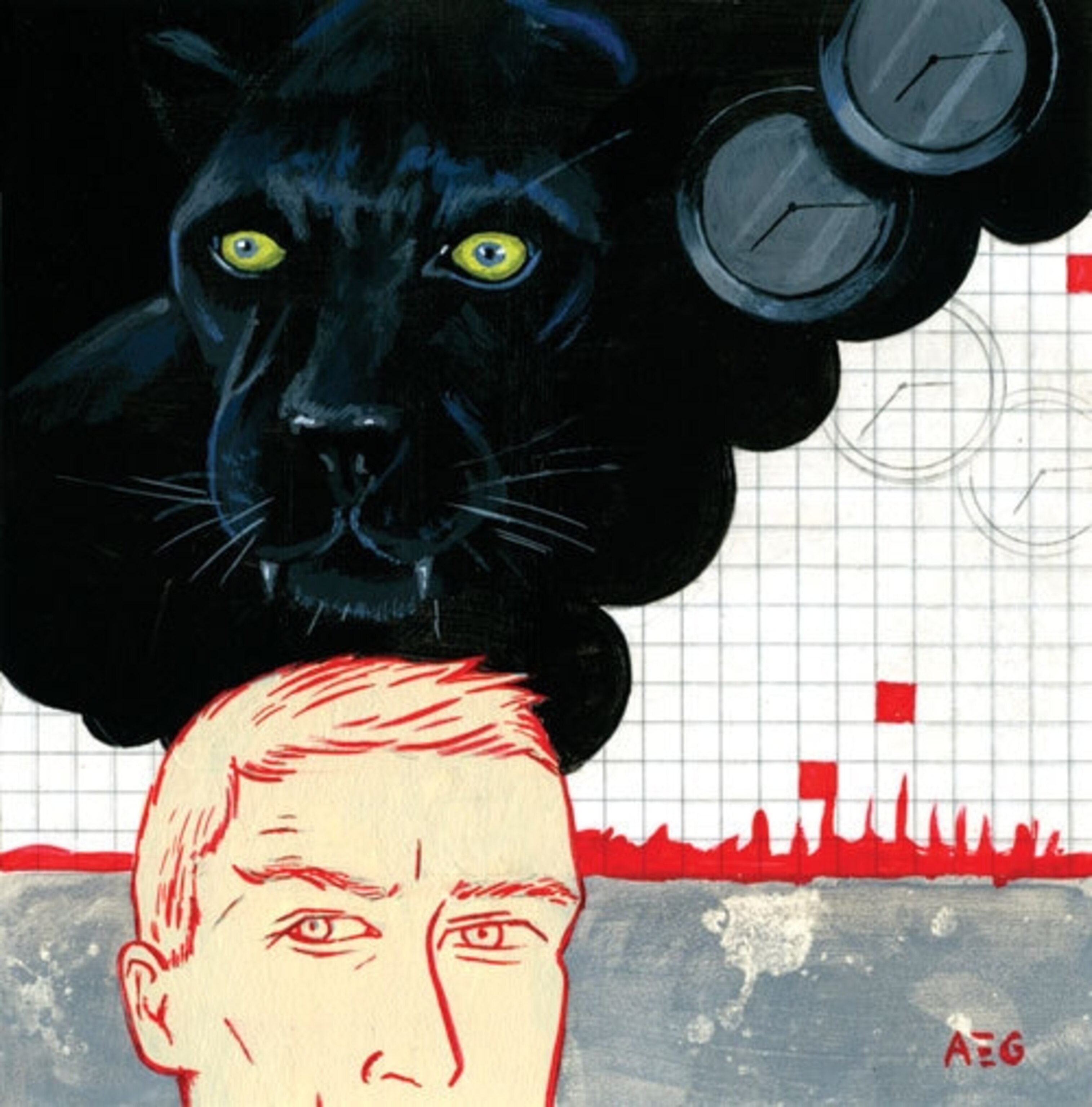

Illustration by Arthur E. Giron

When Peggy Orenstein, a best-selling author, was told that she had breast cancer, she remarked with odd detachment how curious it was that the colors all drained out of her world. She noticed “how the colors in my home office . . . went flat. Isn’t that odd, I thought, looking down at my newly alien torso. My red shirt has turned gray. My red shirt has turned gray, and I might die.”

In emergencies, under extreme stress, it is common for sensory perceptions to change. How we perceive the world—and what good those perceptions do us—are partly a matter of our emotional state. A few years ago I talked to a woman named Jana who had been on vacation in Mexico with her husband, sister, and brother-in-law. One night they all went skinny-dipping in the bay behind the resort. A bit tipsy, they splashed and cavorted and laughed. Then an eight-foot crocodile surfaced behind Jana, and her senses immediately went into a new and unfamiliar mode. As the animal took her head in its mouth, she heard it and smelled its breath and knew exactly what it was, though she had yet to see it. It was as if this knowledge had been handed down to her from an ancient ancestor. Everything shifted into slow motion, and she fought and fought. As she fended it off, the crocodile tore off her thumb, nearly bit her breast off, but she still managed to wrench herself free of its grip. Down and down she swam, thinking clearly: The crocodile would stay on the surface. That was not a panicked reaction but a cold calculation. She was a natural survivor.

Jana found herself looking up from beneath the water, her lungs bursting, and saw the crocodile swimming in circles on the surface, trying to find her. She noticed the moon high above and the tracery of light through the sea, and she saw how beautiful it was, this world, how beautiful and terrible. And she desperately wanted to live. After what seemed like hours, the croc swam off, and Jana surfaced.

That vision of the world, that experience of elastic time and the minute texture of things, used to be part of our everyday existence. Today, most of us catch only the merest glimpses of what that world must have been like, but some of those glimpses are tantalizing. In 1994 in the Auvergne region of France, a park ranger named Jean-Marie Chauvet, along with two others, happened into a cave and found a previously undiscovered site of Paleolithic paintings from more than 30,000 years ago. Among hundreds of images, there were beautiful lions, bears, panthers, and hyenas—all animals that could and did kill people. The discovery of these paintings shook up the world of archaeology, because rarely had prehistoric art been discovered that depicted the animals that preyed on us—only the ones we preyed upon. This art was more sophisticated than any other cave paintings, with shading, perspective, and complex groups in action. It’s easy to see how people who lived in constant contact with predators might be compelled to paint the animals in detail as vivid as what Jana saw.

Everyone experiences these hyper-vivid impressions to some degree when exposed to extreme emotional stress. The normal cause-and-effect relationship of our actions and our perception of their consequences is broken. Crime reports are notorious for their overestimation of time, and the literature of combat and law enforcement is filled with stories of perceptual distortions under fire. Police officers involved in shoot-outs consistently report experiencing tunnel vision and things moving in slow motion.

As Peggy and Jana found, when death comes very close, it transforms us, and we experience the world in new ways. In fact, all that intricate detail, that rich texture, is before us all the time. We just don’t see it. In our day-to-day lives, our brains would soon be overwhelmed by the heightened level of information processing required in short bursts during emergencies. Most of the time, it’s necessary for us to be able to tune out much of the world.

Happily, we don’t need to be in imminent danger to experience the richness of the world around us. Novelty will do. When we become aware of something unfamiliar—when a strange animal or potential mate wanders by—we turn toward it and focus our attention. All animals exhibit this so-called orienting behavior. It is the first step in determining whether something is potentially dangerous, beneficial, or can simply be ignored.

In the presence of novel stimuli, as with obvious danger, time seems to slow down. When this system works properly—and it doesn’t always—our senses give us a blast of rich information just when we need it most, which in turn allows us to act quickly and correctly. We perceive everything, including our own internal state, at its highest resolution. And whether we are frightened or experiencing love at first sight, everything unnecessary falls away.

Children experience something like this continuously. For them, everything is new, and they’re doing tremendous amounts of work to assign emotional significance to it all. It’s just exhausting. And it takes forever, because time seems to go so slowly. That’s why a day seems so long when you’re five years old.

As we grow older, especially in an environment that is contrived to be (or seem) safe, there is less novelty. More and more of the world becomes interpreted and categorized and falls into the background. Time seems to speed up. As people age, the years seem to fly by, partly because there isn’t a lot that’s new. One of the tricks of mindful awareness, the sort of awareness that can help you make correct decisions and protect you from harm, is that you can make everything new again. You slow down, examine things closely, try to appreciate every facet of what’s around you.

It’s what Zen practitioners refer to as “beginner’s mind.” It’s also why we go to new places, why we seek out novelty and excitement. When you go to the wilderness or an exotic land, what you’re implicitly saying is: Surprise me. Seeking novelty and surprise, doing what you’re not used to doing, is a prescription for triggering that ancient perceptual richness that helps us to live more fully.