Cave Explorers Find New Fossils of Mysterious Human Relative

Speaking live from South Africa, paleoanthropologist Lee Berger announced the discovery of bones he says belong to the species Homo naledi.

A new trove of fossil bones found in a cramped South African cave is adding to our understanding of an unusual cousin of modern humans, scientists announced on September 13.

Broadcasting live from South Africa’s Rising Star cave system, paleoanthropologist Lee Berger revealed that ongoing excavations have uncovered new skeletons in the Dinaledi Chamber—four years to the day after the chamber’s discovery.

This site is famous for yielding the first fossils from a previously unknown human relative named Homo naledi. Announced in 2015, the tiny-brained species sports a remarkable mosaic of modern and archaic features. H. naledi’s foot is nearly indistinguishable from a modern human’s, but its shoulders and torso are more apelike.

But unlike any of the previous discoveries, excavators found the new remains at the base of “the chute”—the 7.5-inch-wide, 40-foot slot that modern explorers use to enter the chamber.

“One of the big questions from the beginning of the Homo naledi expedition was: did Homo naledi come down the chute?” said Berger, a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence. “No one believed that was possible; in fact, I think most of us had our doubts.”

Down the Chute

It may seem like a small detail, but the new fossils’ location is important, since it informs ideas of how—and why—this tiny-brained human relative ended up deep within a complex cave system.

Berger thinks that despite its small brain, H. naledi was no intellectual slouch. Its brain may have had a surprisingly humanlike structure, and its hands could have made and manipulated tools, he argues. For now, though, scientists have not found any stone tools in association with H. naledi.

Perhaps the most controversial part of the H. naledi debate involves Dinaledi itself. Berger’s team has argued that the individuals found so far must have entered Dinaledi through the chute—but unlike today’s spelunkers, some H. naledi may not have entered the chamber alive.

Instead, the team posits that some of the skeletons ended up in Dinaledi because the ancient species deliberately disposed of its dead by navigating to the chamber and tossing dead bodies down the chute. This kind of mortuary behavior is usually associated with modern humans and their large-brained relatives, including Neanderthals.

The body-disposal idea has met its fair share of criticism, with some scholars suggesting that H. naledi may have entered Dinaledi through alternate passages that have since collapsed. But if H. naledi bodies had in fact entered the chamber via the chute, skeletal remains would likely have piled up in the debris cone near the chute’s mouth.

Near the bottom of this debris cone, the team claims to have found bones entombed in sediment—and Berger says that they belong to H. naledi.

“The importance of the discovery is that it means that H. naledi, at least some of them, did come down the chute, they did come down through those narrow confines,” he said. “That’s a major discovery for us and, I think, very exciting for paleoanthropology.”

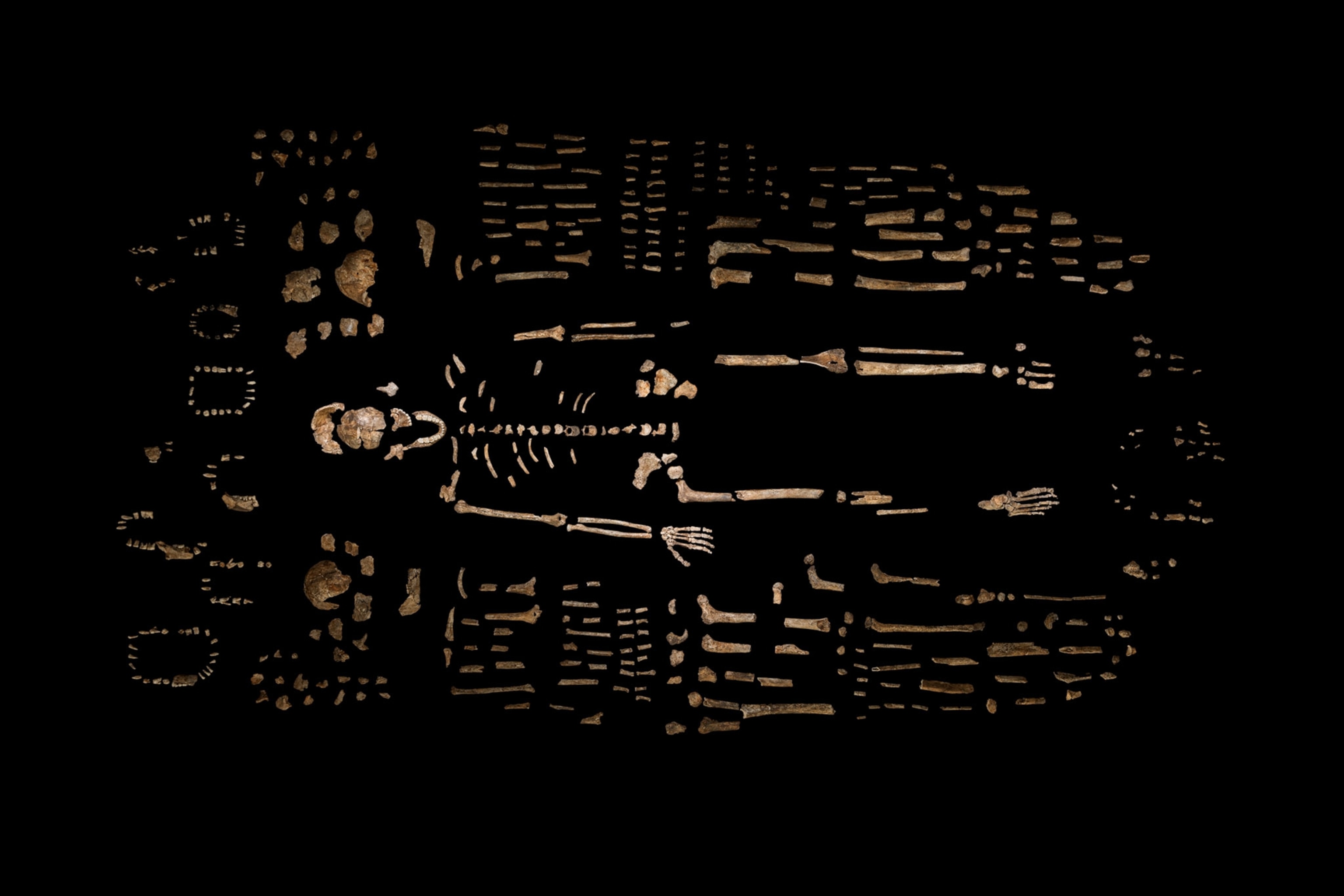

On September 26, the team reported in a livestreamed video that the debris cone contained teeth, skull fragments, articulated hand and wrist bones, and portions of a ribcage. It’s possible that these remains all came from the same individual, but scientific study of them will likely take months to years.

The team also hasn’t specified which of the cave’s sediment layers contain the newfound skeletons, making it impossible at present to confirm the bones’ age. If they’re within the layer that bore the 2015 H. naledi remains, they are likely between 236,000 and 335,000 years old.

Though study of the new bones is just beginning, team scientists are cautiously optimistic.

“We have recovered several hominin specimens from an area near the base of the chute, from beneath the current sediment surface,” says University of Wisconsin-Madison paleoanthropologist John Hawks, a member of Rising Star team.

“For this reason, we are comfortable saying that the main goal of this excavation in the Dinaledi Chamber may have been met.”