The Mysterious Discovery of a Continent That Wasn't There

Robert Peary claimed he discovered a new land mass in the Arctic. Was he lying?

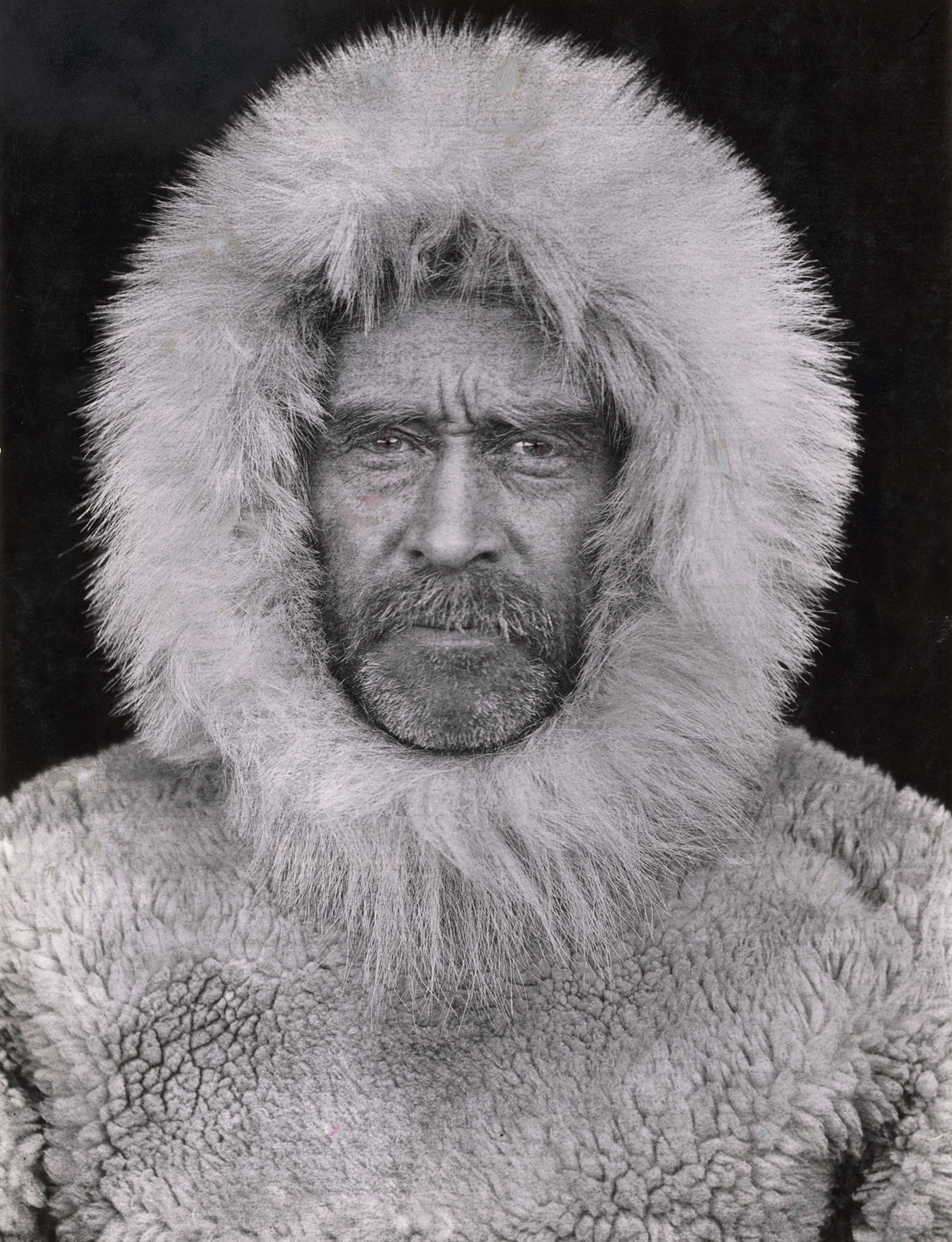

In 1906, legendary American explorer Robert Peary returned from an unsuccessful attempt to reach the North Pole with an astonishing revelation: He had discovered a new continent, a giant island floating in the middle of the Polar Sea, which he named Crocker Land after the sponsor of his expedition. There was only one problem: It didn’t exist.

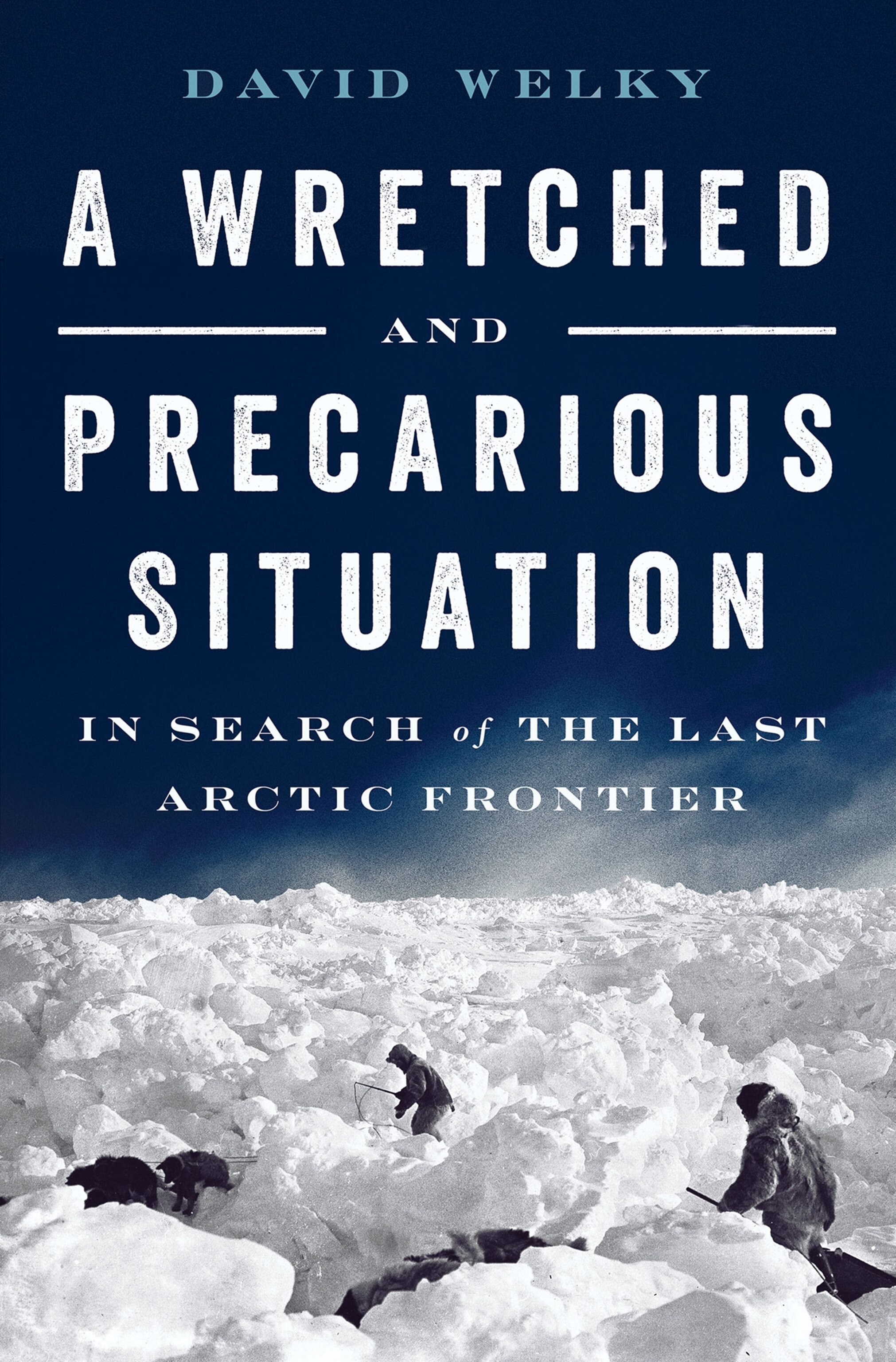

In A Wretched and Precarious Situation: In Search of the Last Arctic Frontier, historian David Welky unravels the strange story of one of the world’s greatest discoveries that never was—and asks whether the grand old man of American Arctic exploration was guilty of telling one of history’s biggest whoppers.

Speaking from his home in Conway, Arkansas, Welky explains why circumstantial evidence led people to believe there was another continent at the top of the world, how one of the explorers on a later mission to Crocker Land murdered an Inuit and died a junkie, and why Peary’s story about Crocker Land was not finally disproved until 30 years later.

Crocker Land has been called “the lost Atlantis of the North.” Put us on the map—and describe its lure for American explorers.

Geographically, Crocker Land would be west of Greenland and north of Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic. In 1906, Robert Peary made an unsuccessful attempt to reach the North Pole. He was despondent, so he decided to set off on a side trip to the west. There was a little sliver of unexplored land there and he thought, I can go there and at least bring home some new discovery. He goes west across Ellesmere Island, looks out over the polar sea and sees what he describes: mountains and valleys, this immense landscape covering much of the horizon. He comes back to the U.S. and reports on this new find in the book he wrote about the expedition, Nearest the Pole. He names it Crocker Land after a banker in San Francisco, George Crocker, who had given him about $50,000 to help put together the 1905 to 1906 expedition. That’s how it found its way onto the map. If you look at maps of the Arctic from 1910-1913, you’ll see this little, moon-shaped island.

Why did it catch fire with other explorers?

Peary claimed the North Pole in 1909 and the South Pole was attained soon after, which left Crocker Land as the last great unknown place in the world. Scientists looked at tide charts and other evidence from the Arctic, like the drift of ships traveling in the ice, and concluded that there was this giant landmass out there.

By 1910 to 1912, what is left unexplored in the world? You’ve got some little interior Amazon areas, parts of the Himalayas, but you’ll never have another chance to discover the last continent on Earth. What’s bigger than that? This became a patriotic mission to claim Crocker Land for America, very much in the vein of that Teddy Roosevelt hyper-nationalism and hyper-masculinity.

Explorer Donald MacMillan took up where Peary left off. Give us a character sketch and explain why he was so drawn to the search for Crocker Land.

MacMillan was born in Maine, a child of the American North, who has been neglected in the pantheon of American explorers. He imagined himself a scientist. He was interested in birds, biology, and anthropology, a kind of polyglot. He has a rough childhood. He grows up in Provincetown, Massachusetts. His father, Neil, was a ship captain, and when MacMillan was about nine years old, his father sailed north to pick up some cod and the ship went down somewhere off the coast of Newfoundland. His mother tries to hold the family together but they can’t pay the rent and she dies when he’s about eleven. He’s bounced around between various families and eventually has to relocate back to Maine. He has to scrape by on his own, so goes diving for pennies that tourists toss in the water, collects flowers to sell, and works his way through Bowdoin College.

He idolized his father as this man of the sea, of the north, and wanted to be like him. Peary craves fame. MacMillan is a modest person, who views himself as more of a scientist than the glory-hunting pole-seeker. He tries for years to get on Peary’s expedition. When he finally went north and arrived in Greenland and saw all these amazing places that he’d read about, he spoke of catching “Arctic fever.” He loved the people, the landscape, the plants and birds. Everything about it excited him.

One of MacMillan’s “Crockerlanders” was a young man named Fitzhugh Green. He wasn’t your typical explorer, was he?

He was not. [Laughs] He was born in St. Joseph, Missouri, to a family with an illustrious history but which had fallen downward into the lower middle class. His mother was a pushy woman who convinced Fitzhugh that he was destined for greatness. He’s clearly a bright, intelligent guy. Is he a once-in-a-century talent? I don’t think so. He joins the Navy, serves at sea mostly in the Caribbean, but is driven by his mother’s belief that he will be great and so becomes an explorer.

Besides being energetic, hard-working, and smart, he had inner demons and was painfully introspective. He writes painful poetry about the other people inside of him, about murders and dark nights. He was a fan of Edgar Allan Poe and took Poe’s novel, Pym, to the north with him and adapted it into an unpublished short story. Nobody knows how he or she will respond to extreme situations; once in the Arctic, Green falls apart. The Arctic nights drag him down, and he absolutely cracks.

One of the most dramatic moments in your book is the murder of an Inuit named Piugaattoq by Fitzhugh Green. Present the case for the prosecution—and explain why Green never actually faced justice.

Good question. The easier part of that is why Green was never prosecuted for murdering Piugaattoq. That has to do with how Americans viewed native people. Green was quite open about having murdered him. When he got back to the U.S. in 1917 he even wrote about it in his articles. It was almost the sense that it didn’t matter because—

He was just a native …

Yeah, he was just a native. It was an emergency. Piugaattoq was trying to escape and was going to leave Green trapped in the wilderness, so he shot him to get his sledge. You could make a self-defense argument, and it’s just someone from some place we’ll never go, some native. MacMillan and the American Museum of Natural History, which sponsored the expedition, wanted to, figuratively, bury the whole thing. They just didn’t want any bad publicity.

There was an extraordinary coda to the story of Fitzhugh Green, wasn’t there?

He comes home in the middle of World War I, rejoins the Navy, serves on battleships during the war, and becomes a minor war hero, but he’s always chasing fame and fortune. For a time, he hangs around with the great pilots of the 1920s, like Bird and Lindberg. He marries the daughter of the man who founded General Motors, travels to Europe and Africa. But it all falls apart in the 1940s, when he and his wife are arrested for being involved in a strange scheme, involving a South American diplomat, to acquire drugs. It’s not clear exactly what but probably opiates. They couldn’t get the drugs, and Green ended up in hospital with withdrawal. Despite the façade, he was clearly in really bad shape. Simply put, he was a junkie and probably had been for quite a while. He ended up dying soon after of heart problems. A tragic end to a tragic life.

You call Crocker Land “an illusion that grew into a lie that took on a life of its own.” Peary is the grand old man of American Arctic exploration. Was this just a giant porky to boost book sales?

When Robert Peary comes back to the U.S., he says nothing about Crocker Land. I’ve been through his correspondence, including letters to George Crocker, and he says nothing about it for months after he returns. Then, in 1907, he releases his book, and suddenly here are these paragraphs about this amazing new land. It’s not for many months after his return that he finally says something.

Crocker Land is a fabrication by Peary from the start. You can look at this in any number of ways, starting with circumstantial evidence. Obviously, Crocker Land isn’t there. So, let’s give him the benefit of the doubt. What might he have seen and mistaken for land? It could have been an ice island, but ice islands don’t have peaks and valleys, they’re flat on top. Do we really think that the most experienced Western Arctic explorer mistook an ice island for a continent?

It could have been a mirage. A fata morgana, as this particular kind of mirage is called. Subsequent explorers have seen fata morganas from that same spot. If you watch one, you will see it wobble and flicker and waver, and it’s obvious it’s not solid land. Nothing Peary might have mistaken for Crocker Land makes sense. That’s strike one.

We can also look at his care notes, the notes he leaves behind to prove he was there. They’re quite detailed notes. He talks about a hunting trip that day, climbing the hills to get this view, but says absolutely nothing about seeing Crocker Land. Several crewmembers also kept diaries, and according to those he never mentioned anything about seeing a new continent. We also have the typed drafts for his book, Nearest the Pole, and for an article he excerpted in Harper’s Magazine. But again there is no mention of this new land mass.

In other words, sometime between the final manuscript and when the book comes out the paragraphs about Crocker Land mysteriously appear. It’s all pretty damning.

If Crocker Land turned out to be the proverbial crock, why did so many people fall for the illusion? And what does science and geography tell us today?

They fell for it because they learned about it from the most authoritative source that Americans had on the Arctic. Robert Peary knew more about the Arctic than any other American or Westerner alive. In that sense, it was an unimpeachable source.

The best science we had at the time also said there must be something up there, based on the drift paths of ships frozen in the ocean and how the tides operated. There was observational evidence of birds flying in that general direction way out on the polar sea and animal tracks leading in that direction. There were also Inuit stories about relatives who had been to this place. All of this suggested that there was a large landmass in the center of the polar sea. So they read the evidence in that direction in a phenomenon known as confirmation bias.

Today, we know they were actually right about a lot of things. They noticed the ocean current enters the polar sea through the Bering Strait between Russia and Alaska, splits in two directions, then reunites and goes out by Greenland. So, there is something that’s separating the currents there. But it’s not Crocker Land. It’s what is known as the Beaufort Gyre, a huge, spinning current that keeps things from drifting into it. But it wasn’t until the dawn of long-distance air travel that we could be sure. In 1938, a pilot named Isaac Schlossbach flew an airplane over the region where Crocker Land was supposed to be. And, of course, there was nothing there.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.