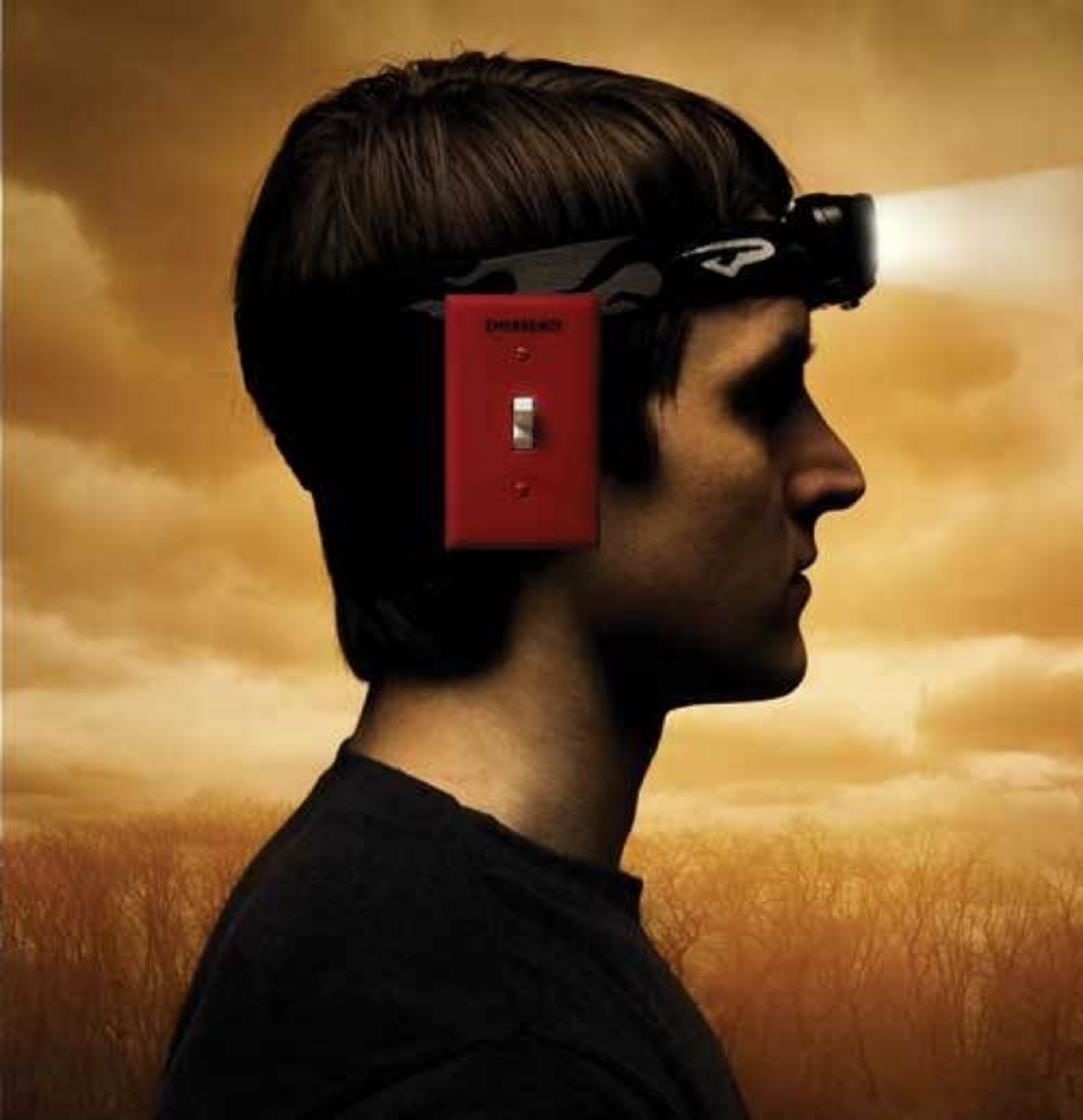

Deep Survival: Brain Vs. Gadget

On a solo backpacking trip this winter, reader Nate Freund was stranded high on California’s Ontario Peak during a snowstorm. Read his story, then see Deep Survival author Laurence Gonzales’s analysis of the situation.

Submitted by Reader Nate Freund

After reading your article "Folk Wisdom" in National Geographic ADVENTURE [April 2008] I was inspired to write to the author whose concepts played a critical role in my survival.

On January 22, 2008, I set out for a solo backpacking trip to summit Ontario Peak of the Cucamonga Wilderness. I was rescued by Search and Rescue Forces from the San Bernardino Mountains after a U.S. Air Force satellite detected my distress signal from my Personal Locator Beacon. It was the first successful rescue of this kind in California: One initiated from a legitimate activation of a personal EPIRP carried by a recreational hiker.

I had spent months staring into the snow-capped mountain range from the Claremont roads as I drove to school everyday. My third attempt to summit this season began on a clear Sunday morning. After hiking a mile above the city, I set up camp on top of Big Horn Peak. I woke up the next morning to see clouds covered everything below me.

Nothing in my previous experience told me I was in danger as I continued to climb toward my destination, though fowl weather was approaching. After a successful summit, my descent was blurred by a snowstorm and dense fog. Multiple attempts to descend failed. I was forced to fight my way back to base camp, my last familiar location, in knee- to waist-deep snow. A 15-minute panic ride down the wrong side of the mountain cost me two hours of valuable time to climb back up to the ridgeline where I regained my bearings.

At that point I sent out a text message to my roommate and activated my Personal Locator Beacon (a gift my father gave a year ago, along with your book). Then I made shelter, focused on maintaining my core temperature and conserving energy, and waited. Less then 24 hours later I was found by multiple teams that brought me back, uninjured, and in high spirits.

A number of key lessons from your book contributed to my successful rescue. Understanding the human emotional stages of such a life-threatening situation helped me go from panic to acceptance very quickly. "Be here now," I thought to myself. Later that night, in my tent wrapped around a tree to keep it from sliding down the mountain, another Deep Survival lesson came to mind: Break down every action into small missions to help remain focused. Crunched in my sleeping bag, I turned the smallest movements into missions—a mission to find my water or granola bar; a mission to ready my light and signaling devices in case a helicopter would come; a mission to twinkle my toes a hundred times to postpone frostbite. As insignificant as they may seem, each task kept my mind alert. As hours in the frozen night past by slowly, I thought of stories I had read about people who had been lost in the wilderness without basic survival gear or shipwrecked parties withstanding the elements. They reminded me that I could survive as well.

My logical mind, built from years of previous hiking adventures, overruled my emotional feelings that would have avoided the situation all together. A hundred hikes out of a hundred hikes before told me I would always find the trail back. This gives me a logical zero percent probability of getting lost in the future. How untrue this turned out to be.

Laurence Gonzales Responds:

Wow. Sounds like you were nearly voted off the ultimate reality show: Your life.

Your comment that you "had spent months staring into the snow-capped mountain range from the Claremont roads as I drove to school everyday" struck me as significant.

You were rehearsing in your mind what you were going to do. You were creating what I call a mental model of your expected world and a behavioral script for what you were going to do in it. I would imagine that you unconsciously had all your moves planned before you ever got on the mountain, including the joy of reaching the summit. This is good. This is how dreams become reality. But these mental models and behavioral scripts can set traps for us and must always be viewed with caution.

As a lifelong pilot, my rule about weather is simple: If it looks bad, it is bad. I have always tried to apply that in the mountains, too, where slow-moving junk can be shoved upward by terrain and turned into a deadly storm. We should never regret going down to live another day. The summit doesn’t move much (except on Mount Saint Helens), so it’s a pretty easy target to find when conditions are right.

Good for you for backtracking to base camp. People rarely backtrack, being too frightened and too fixated on the idea of just getting down. "Get-Home-itis" is a deadly disease.

- National Geographic Expeditions

And good for you for being so well prepared. The search and rescue volunteers I know always pack as if they’re going to spend the night. That means when things turn bad, they can always hunker down with the confidence that they’ll wake up in the morning with all their digits still attached. It’s a free extra day of camping.

EPIRBs… Hmmm… They’re now called emergency position indicating radio beacons, but I hope we find a better name for that gadget. How about a Here-Eye-Yam? Then the acronym would be "Hey!".

I’m ambivalent about both the beacons and about cell phones. In your case, I think the gizmos worked the way they’re supposed to work. In other cases, I know that they have simply made people careless or lazy and endangered dedicated search and rescue teams. And always remember, the Model 1.0 Human Brain does not require batteries, which don’t like the cold.

Glad you’re among us. And very glad this column and my book, Deep Survival, were able to help you through.