Discover Fascinating Vintage Maps From National Geographic's Archives

More than 6,000 maps from the magazine's 130-year-long history have been digitally compiled for the first time.

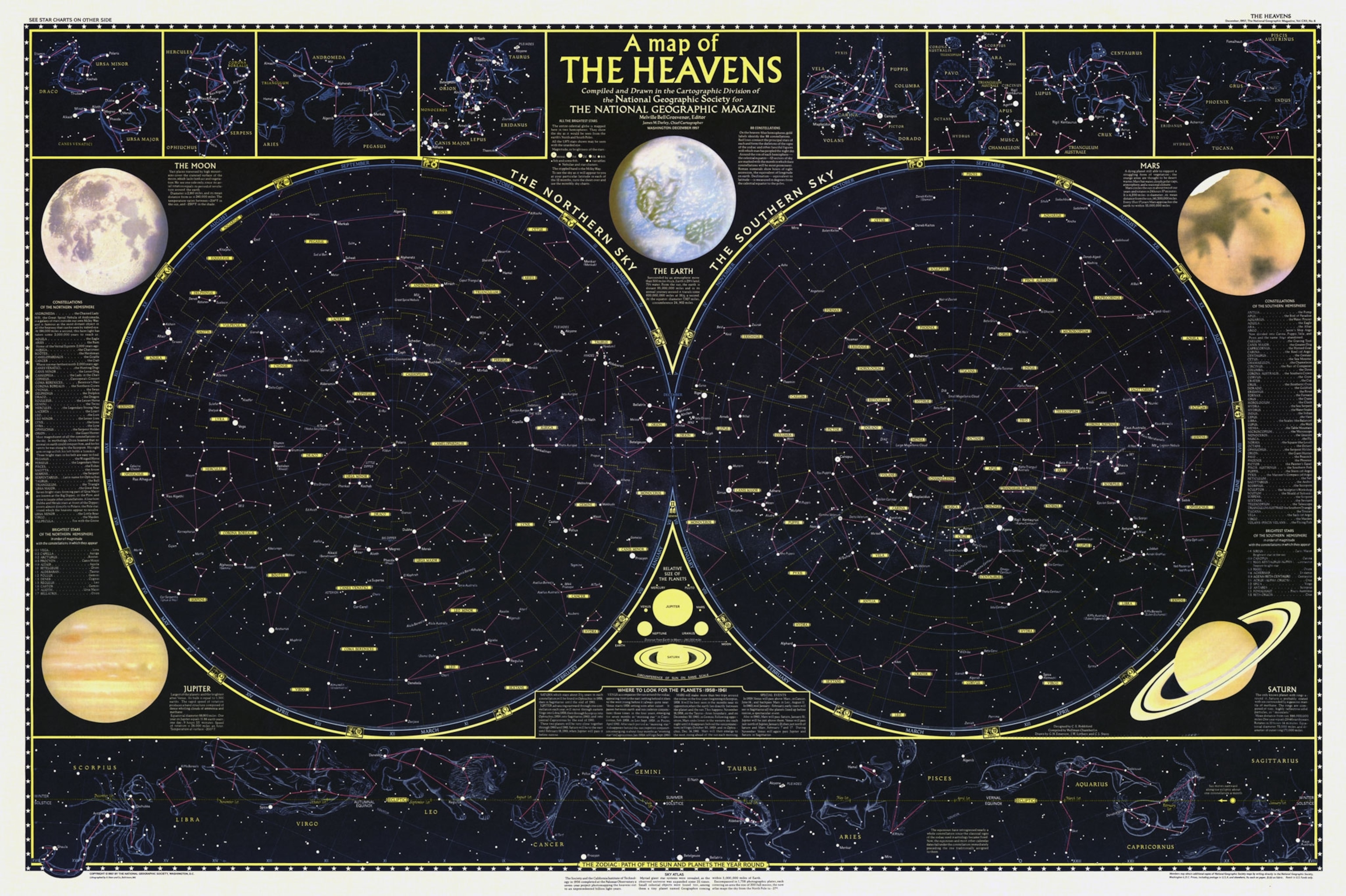

Cartography has been close to National Geographic’s heart from the beginning. And over the magazine’s 130-year history, maps have been an integral part of its mission. Now, for the first time, National Geographic has compiled a digital archive of its entire editorial cartography collection — every map ever published in the magazine since the first issue in October 1888.

The collection is brimming with more than 6,000 maps (and counting), and you’ll have a chance to see some of the highlights as the magazine’s cartographers explore the trove and share one of their favorite maps each day. Follow @NatGeoMaps on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook to see what they discover. (The separate map archive is not available to the public, but subscribers can see them in their respective issues in the digital magazine archive.)

“It’s inspiring,” says Martin Gamache, National Geographic’s director of cartography. “There's tons of stuff in there that struck me as being innovative and interesting.”

We’ll be digging through the collection as well to bring you stories about some of the most intriguing maps we find. The gallery above includes some tantalizing examples, such as the first composite map of the United States created out of color satellite photographs, and a clever way to get around Moscow’s ban on aerial photography in order to create a birds-eye view of the Kremlin.

The very first maps published by National Geographic in 1888 depict one of the most severe blizzards to ever hit the United States (below). Nicknamed the Great White Hurricane, the three-day storm crippled the Atlantic coast from the Chesapeake Bay all the way into Canada, dumping almost 5 feet of snow in some places and creating 50-foot snowdrifts. National Geographic used a set of four maps to document temperature, pressure, and wind patterns on successive days as the storm lashed the coast.

The maps accompany a blow-by-blow description of the conditions that fed the storm, written by Edward Everett Hayden, a meteorologist and one of the 33 founders of the National Geographic Society. Hayden’s article also included a gripping account of the travails of one ship as it struggled to survive the violent blizzard. “Just before midnight a heavy sea struck the boat and sent her over on her side,” he wrote. “Everything moveable was thrown to leeward, and the water rushed down the forward hatch. But again she righted, and the fight went on.”

It was the start of a long tradition in National Geographic magazine of enhancing storytelling with maps. The maps of the storm were likely made by the U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office, and the magazine continued to work with various outside mapmakers like the U.S. Geological Survey until it established its own cartography shop In 1915. Over the next century, the National Geographic cartography department made thousands of maps for the pages of the magazine and hundreds of poster supplement maps.

The goal of the cartography team, Gamache says, is to capture readers’ imagination by conveying a sense of place, to give the viewer an idea of how a place might look and feel. “I think when we're successful, it resonates with people," he says.

It took months to extract all the maps from the magazine’s digitized back catalog and compile them into a separate collection. Gamache says the resulting trove will help the current staff cartographers connect to the magazine’s legacy as they continue to try new things. “It's always good to look at what we've done in the past on any subject,” he says. “It gives us ideas.”

As they share a curated selection of maps from the archive, the cartography team will be highlighting some of the maps that have served as inspiration for new maps, says research editor Irene Berman-Vaporis.

One of the things that defines National Geographic magazine’s cartography is the way it is integrated into the rest of the magazine’s editorial process. Each map tells its own story, but also works alongside text and photography to bring another dimension to the article, Gamache says.

“A map is able to connect with somebody in a different way than a text will or a photo will,” he says. “They engage with a different part of our psyche or our brain.”

Stay tuned for more stories about National Geographic’s editorial map archive here on All Over the Map. And see a different map from the archive every day by following @NatGeoMaps on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.