Secrets of the world’s greatest trailbuilders

Around the world, trail designers are quietly employing surprising techniques to engineer awe. You’ve probably felt it without even knowing why. Inside the creative science that’s transforming your time outside.

In southern Patagonia, a trail ascends a mountain to a renowned and beautiful lake. The trail was formed over several decades by climbers intent on scaling the granite spires of Argentina’s Fitz Roy chain. Climbers, being who they are, walked straight up the mountain from their camp at the chalky and rushing Rio Blanco below. In the 1990s, hikers began to outnumber the climbers, drawn by the sight of the emerald lake surrounded by an amphitheater of rock and ice. The trail eventually took the name of the lake, Laguna de los Tres, colloquially translated as lake of the three peaks, and over the next 30 years, the number of visitors who flocked to the nearby town of El Chaltén to hike the 14-mile out-and-back trail swelled from roughly 30 a day to 3,000. As these crowds trampled through the vegetation and exposed soil that was carried away by wind and water, parts of the trail gradually expanded into a rock-strewn abrasion as wide as the two-lane highway that leads into town.

On a cloudy March morning, Jed Talbot, 49, peered through a device called a clinometer that he wore on a necklace, as he scouted the woods around Laguna de los Tres’s most problematic pinch point, the rutted and extremely steep final 1.2 miles to the lake. He and his partner on the project, 45-year-old Willie Bittner, were using clinometers to “shoot grades,” or find a sustainably graded track across the slope. The pair have worked together to build new trails and rethink deteriorating old ones for decades, and they resemble one another in both appearance and spirit—bearded and woodsy, with the wholesome field-savviness of Boy Scout troop leaders.

Bittner walked ahead of Talbot, stopping several yards away. Talbot squinted through the clinometer and called adjustments—“We can go higher,” he said—until Bittner reached a 10 percent rise, about the limit of a standard treadmill. Then Talbot walked to him while running the GPS tracking app Gaia on his phone, so that as he moved, the app mapped his route up the hillside. By the end of the day, ideally, it would be a track that will become a trail.

A lot of trailbuilders rough out a line on a map before they venture into the field. But Talbot rarely sketches before he scouts, purposefully avoiding preconceiving notions of a route before he can walk the area. He wants to see where the terrain leads him. “I feel like the guidance from the landscape versus a line I draw in the office leads to a different result,” he says.

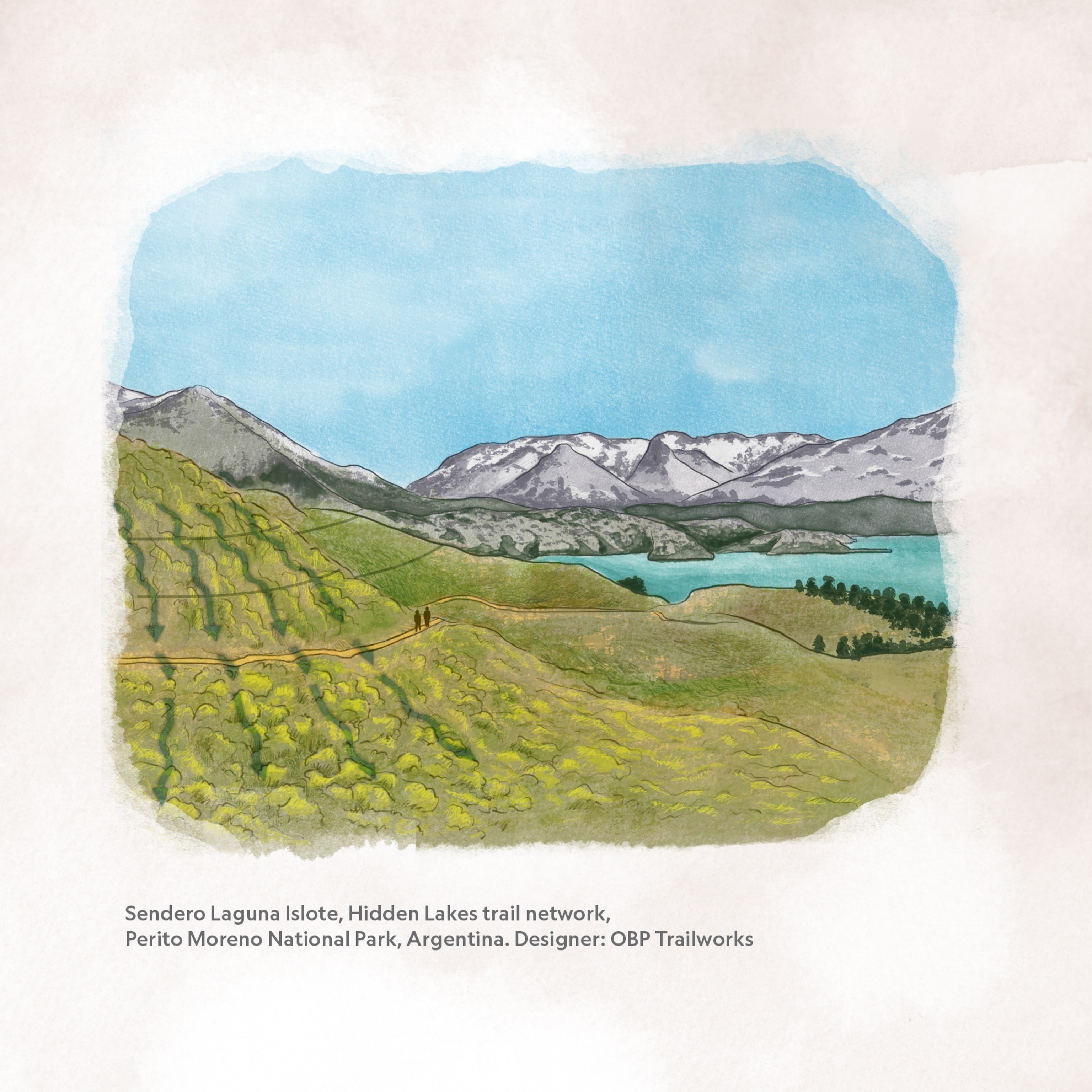

Talbot is among the top designers in the booming professional trailbuilding industry. From the United States to Saudi Arabia to Romania, community planners have realized that finding affordable ways to bring people back in touch with nature not only boosts their happiness but also represents a solid investment for tourism. In the past decade alone, Talbot has led the design on two of the field’s standout projects, both in remote Patagonian locations: more than 60 miles of new trails in Perito Moreno National Park, created from 2017 to 2019; and over 30 miles of trails around Cave of the Hands, a UNESCO World Heritage site in the Pinturas River Canyon, designed and built from 2020 to 2024.

The Perito Moreno project in particular was a tour de force of trailbuilding in a notoriously rugged and remote environment. In just two seasons, Talbot and Bittner designed the trails and also trained an Argentinean crew of over a hundred—many of them mountain guides—to hand-build them. The nonprofit American Trails recognized it as the most extensive trails development and training effort in Patagonian history when granting it an international design award in 2019.

(Our ancestors walked these trails hundreds of years ago. Now you can too.)

Now Talbot has been hired by a coalition of El Chaltén locals to propose a redesign of the famed Laguna de los Tres trail for Argentina’s Administración de Parques Nacionales (APN). The main problem with the current path is that its route straight up the mountain channels water and forces hikers to displace rocks and dirt as they scrabble up the steep slope. The section Talbot is assessing rises about 1,500 feet and at some points attains the steepness of a black-diamond ski run. It culminates in a near-vertical rock staircase that becomes a treacherous creek when it rains and a two-way traffic jam during peak hours—often at the same time. The eroded trail is dangerous and also not much fun to hike. The energy on this final section is anxious, Talbot tells me. Hikers are stuck in a bottleneck—and it’s physically grueling too.

As we walked through the thick forest of lenga beech trees, Talbot says: “You have one chance to make a scar on this landscape. I don’t take that responsibility lightly.” He aims to make that scar surgical. Trailbuilders want to design and build routes that transport and delight us—and stand up to the accumulated impacts of our footfall. The final product is more than a path through the woods. It’s a reflection of our relationship with the natural world.

Erosion is the nemesis of any trail. Unmitigated, it can turn the most beautiful track into a gaping wound. Water, wind, and people are the culprits, but water is the most problematic, relentlessly flowing down the path of least resistance and carving deep ruts. “Focused water can do more damage to a trail than any user,” states the International Mountain Bike Association’s Trail Solutions manual. Most trailbuilding techniques thus focus on managing hydrology through grade, a slope’s steepness. A sustainable trail follows guidelines that can read like a civil engineering manual: The “half rule,” for example, states that the grade of a trail shouldn’t exceed half the grade of the slope it’s built on, lest it channel water instead of shedding it. Trails also incorporate rolling grade reversals, undulations that drain water at low points; and are outsloped, meaning the outer edge is slightly downhill in order to facilitate water shedding. They’re generally no steeper than 10 percent on average, which prevents user-caused erosion—sustained grades greater than that cause hikers to loosen more dirt as they work harder to travel uphill or down.

Many trails in the United States weren’t built with these principles in mind—in part because they weren’t built at all. Early hiking trails often subsumed what are called legacy trails or old game trails, Native American paths, and other human and animal thoroughfares. Trails that were constructed beginning in the 19th century, especially in the Northeast, often went straight up mountains.

(America has a hidden 740-mile river adventure that’s finally being revealed.)

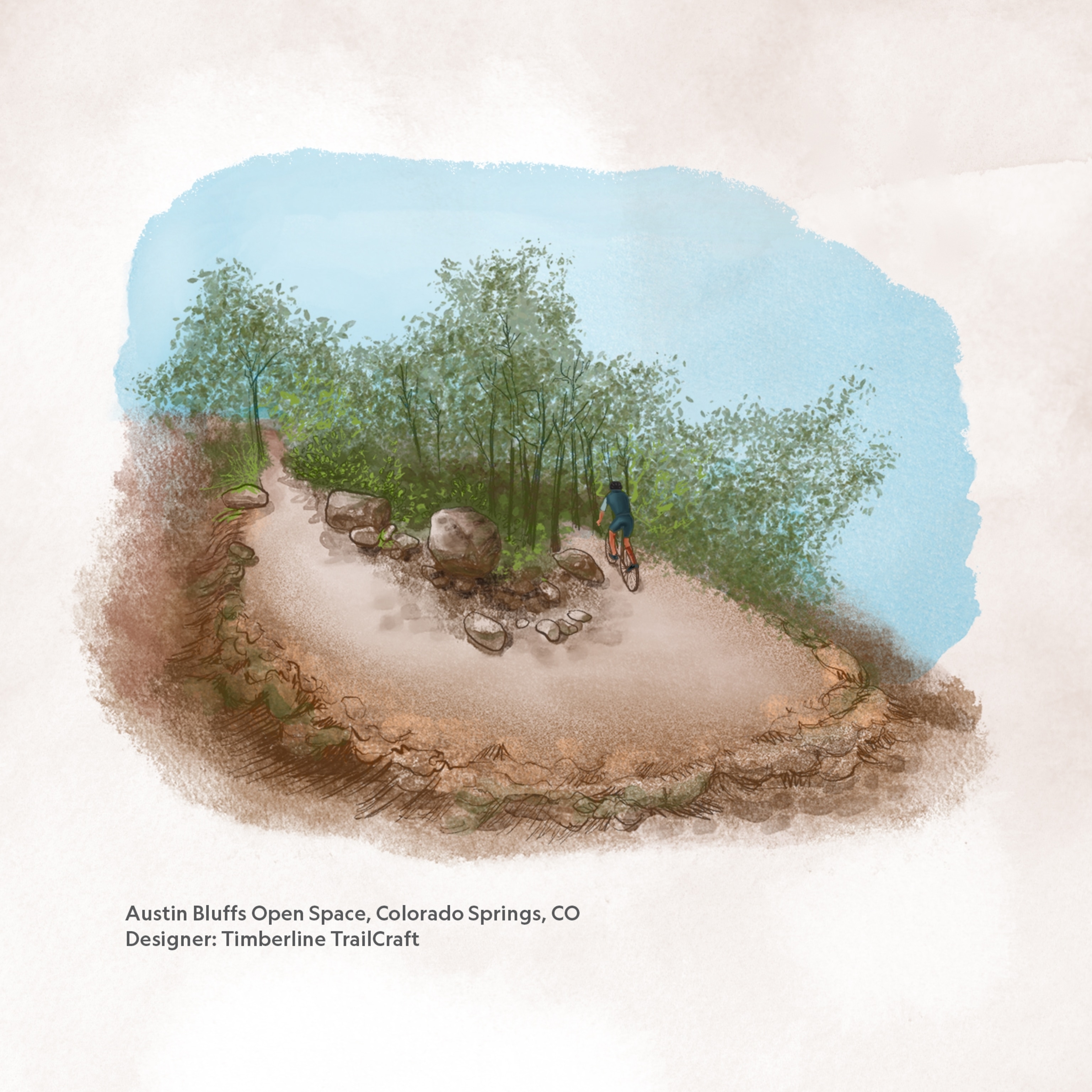

While many of the practices of sustainable trailbuilding were established from the 1920s onward by trailbuilders in agencies ranging from the Civilian Conservation Corps to the U.S. Forest Service, arguably no group did more to popularize the idea of sustainable trailbuilding in the modern era than mountain bikers. The International Mountain Bicycling Association organized in 1988 in response to hikers’ fears that cyclists would destroy trails, and it helped promote guidelines through its nationwide trailbuilding program and its Trail Solutions handbook.

In the ’90s and early 2000s, when sustainable design was taking hold of trailbuilding, “a lot of us had the zeal of the newly converted,” recalls Alaska-based trailbuilder Gabe Travis, who helped Talbot design trails in Perito Moreno. But it soon became apparent that trails adhering blindly to the rules of sustainable design were getting cut by users. “We started to realize that meeting the needs of the intended user is just as important a rule of sustainability,” Travis says. Over time, trail designers became savvier in the art of managing hiker behavior and designing toward the goals of a trail’s target user group. Because if a trail doesn’t go where users want to go, or how—up or down a hill efficiently, for instance, for a fourteener summit trail—they will create their own routes, called social trails or desire lines.

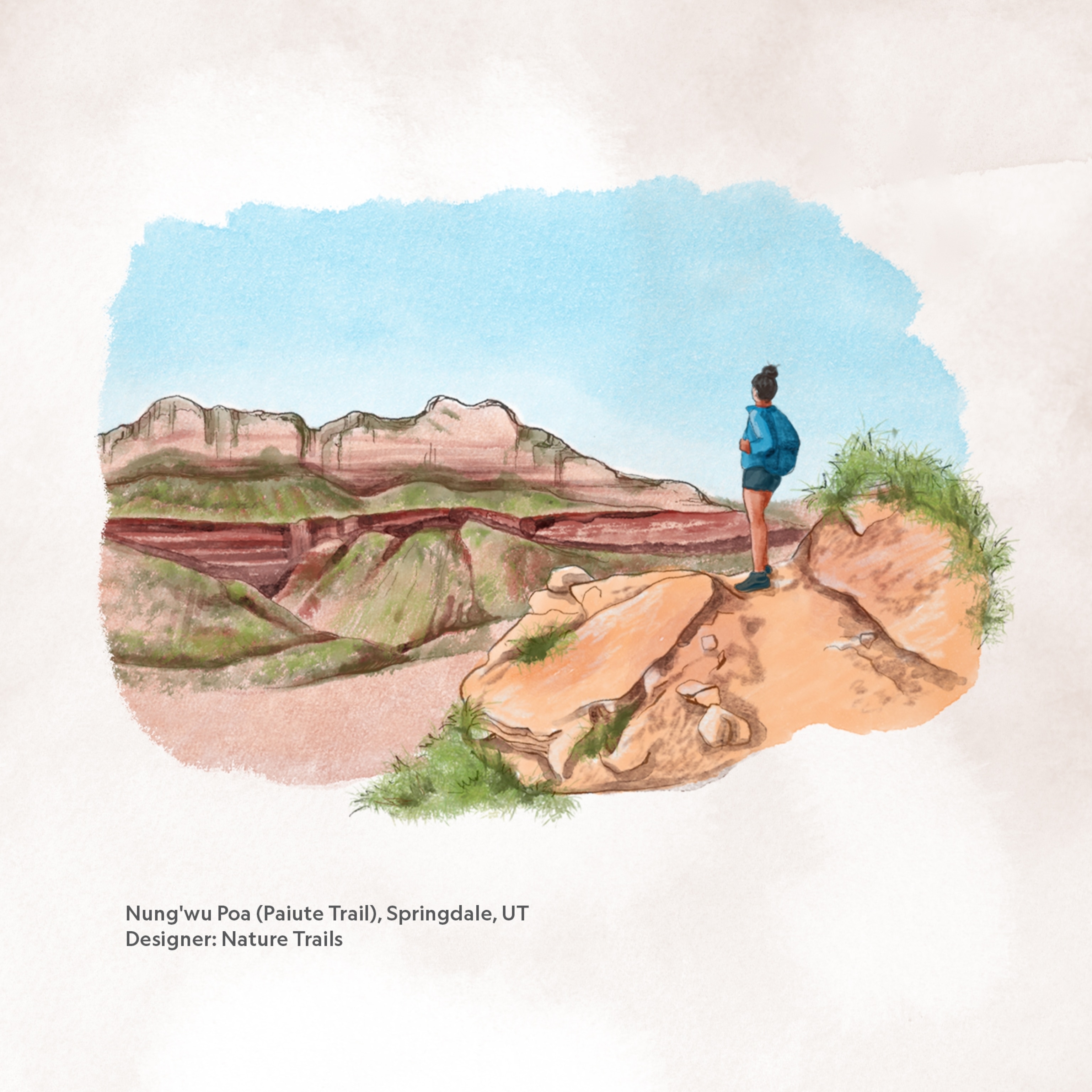

Desire lines, or lack thereof, are the evidence of a trailbuilder’s grasp of not only the hard sciences of the trade—hydrology, geology, and geography—but also psychology. Trailbuilders know you can’t just stop people from doing what they want to do, says Robert Moor, author of On Trails: An Exploration. Fences blocking desire lines in New York City parks, for example, simply get stomped down. “The art becomes shaping people’s desire instead of thwarting it,” Moor says.

“If we do all this stuff really well, people will never know we did anything,” says Colorado-based trailbuilder Scott Gordon. “They don’t feel like they’re being managed.”

In Perito Moreno, Talbot highlighted a clumsy attempt at user management, pointing to what he calls a “gardening path” that was built after his tenure—a trail bordered by pebbles on either side. Besides drawing the hiker’s eye from the environment, bordered trails trap water and feel like “a prison for the hiker,” he says, borrowing an idea from trailbuilder Troy Scott Parker, author of Natural Surface Trails by Design. Rebellious hikers will walk outside them. Talbot prefers to use “confidence markers,” large stones placed intermittently to suggest the route, when needed.

It’s even better if he can just hide the trail from you. In Perito Moreno, Talbot and Bittner designed the trails to be invisible from other points in the park by nestling them among the terrain. They’d flag a section of trail, walk to another vantage point, and make sure they couldn’t see the flags. Not only does this tactic create a sense of wilderness and solitude, but hikers are less likely to cut a trail if they can’t see where it’s going.

Directional changes—turns—can also interrupt flow and encourage trail-cutting, so Talbot deploys them thoughtfully, avoiding stacks of frequent and visible switchbacks. When he does turn a trail, he tries to wind it around a small rise in terrain so the exit can’t be seen from the entrance. He also favors climbing turns—wide uphill bends where a hiker is gaining elevation while turning—over switchbacks, which kill more momentum and are easier to cut. But it’s a tenuous balance. Long straightaways with infrequent turns can be problematic, he says, because people get anxious when they’re aware that they’re moving in the opposite direction of their objective. The trick is to keep hikers engaged enough that they’re convinced they’re on the best route possible. “If you’re fully immersed in your environment,” Talbot says, “you’re not looking for another way.”

Talbot grew up in Maine and started building trails in college in Minnesota, when he joined his school’s conservation crew. He found his people there, he recalled—they were down-to-earth, “happy and dirty.” He regularly slept outdoors in the campus arboretum, showing up to class smelling like campfire smoke.

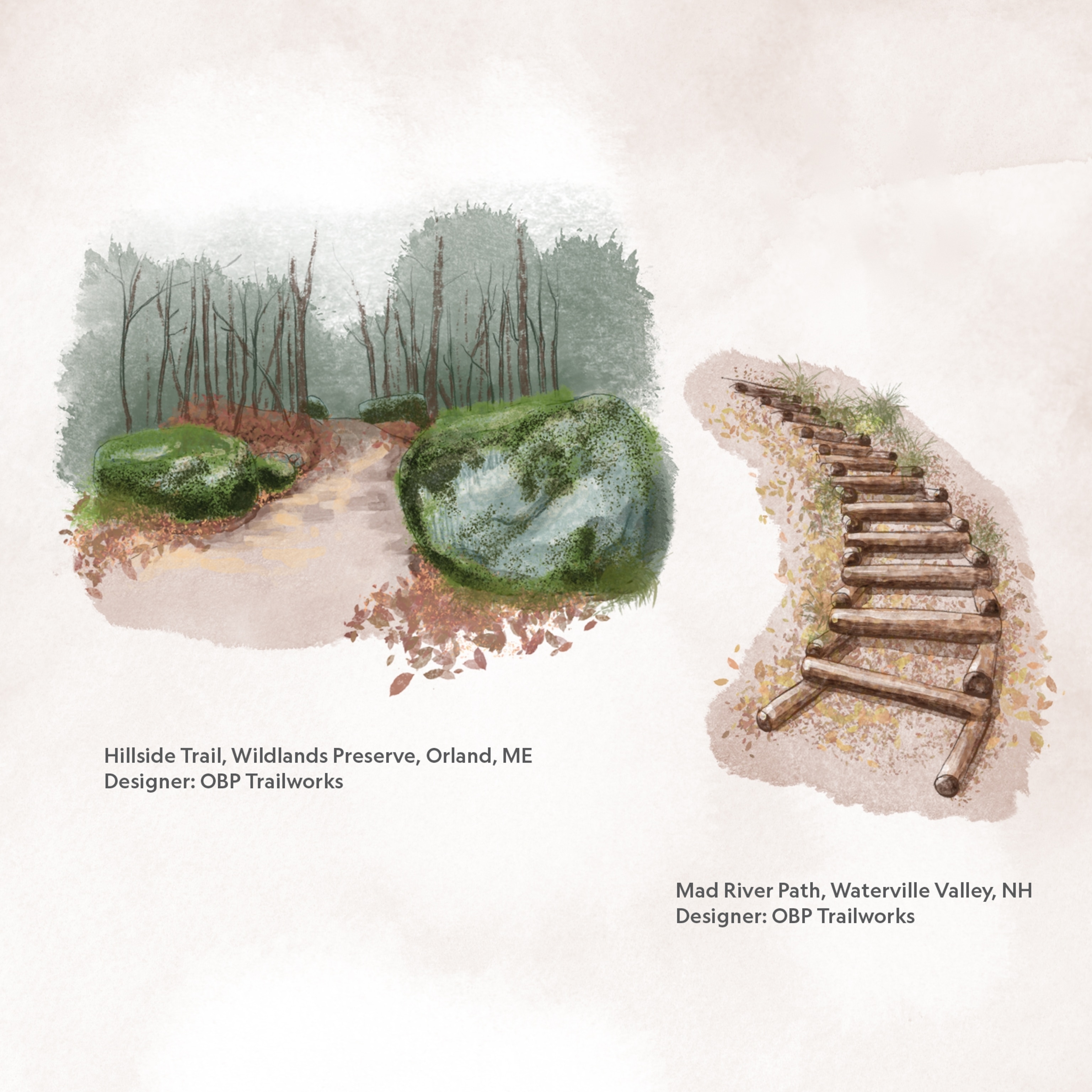

When Talbot graduated in 1998, trailbuilding wasn’t an established career path. “Virtually no one was willing to pay a living wage to build trails,” he says. Talbot enrolled in a program run by Americorps and the Student Conservation Association, which leads youth trailbuilding crews, and learned skills like rockwork, rigging, and chain saw operation. He fell in love with the challenge, physicality, and satisfaction of creating something that served people and protected the environment. For several years after that, he lived out of his truck and traveled around the country training crews for the SCA and working on projects for other trailbuilders, in particular veteran New England trailbuilder Peter Jensen. He learned the same hand-building techniques used by the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration during the trailbuilding boom of the 1930s and ’40s, and was inspired to likewise build trails and structures—like stone staircases and bridges—that could last centuries. In 2004 he launched his own business, which today employs several full-time staff and a handful of subcontractors, and is usually engaged in multiple projects throughout New England and Patagonia.

Today’s young trailbuilders enter a very different industry. Global hiking tourism is projected to grow over 7 percent a year through 2033, according to the market research firm DataIntelo, driven by the increasing popularity of adventure and wellness-based travel. The worldwide demand for professionally built sustainable trails “has just skyrocketed,” says Dawn Packard, former president of the Professional Trailbuilders Association, whose 140-plus member companies represent 20 to 30 percent of the global trailbuilding industry, by its estimate. (Talbot, too, is a former PTBA president.) People seeking more ways to get outside during the pandemic may have played a factor. The number of companies in the PTBA has grown by more than 40 percent in the past six years, while revenue has grown 350 percent to just over $200 million, according to a recent member survey.

Communities have come to see trails as cost-effective infrastructure in the past decade, says Colorado trailbuilder Scott Linnenburger. A new municipal sewer line might cost $30 million, for example, compared to a five-million-dollar estimate to build Baileys, an 88-mile mountain bike trail network outside of Athens, Ohio, that’s projected to generate over $27 million in taxes and tourist spending in a decade.

Most new routes being designed today are mountain bike or multiuse trails often built with excavators and dozers. But when a project is in a designated wilderness area in the U.S., which in most instances prohibits not only motorized access but also motorized tools, or in a remote backcountry location like Alaska and Patagonia, it requires someone like Talbot, who specializes in hand-built backcountry trails.

It’s difficult for the average hiker to grasp how much work goes into any trail, but hand-building in a wilderness area demands a level of effort that can seem practically Paleolithic. Consider the task of drilling a hole through rock without a power tool: Talbot must line up a drill bit on a rock, hit it with a hammer, rotate it a quarter turn, and hit it again—over and over. It takes an hour to drill through an inch of Sierra granite; Talbot and a crew once spent two full weeks in California’s John Muir Wilderness using star bits to drill dozens of three-inch-deep holes so they could insert feather wedges—two L-shaped shims with a wedge driven between them—to split the rock.

On the best trails, hikers enter an almost imperceptible flow state as they’re pulled deeper into the natural world.

For all this work, a trailbuilder usually remains anonymous. “You go out in the woods, you gather material, and you build something you hope people don’t even notice,” Talbot says. “It’s in service to the environment. You don’t sign your name. It’s one of the most beautiful things I could imagine doing.”

On the best trails, hikers enter an almost imperceptible flow state as they’re pulled deeper into the natural world. After a few days shooting grades in El Chaltén, Talbot and Bittner took me backpacking on the trails they designed in Perito Moreno to experience that feeling firsthand. On the Big Loop, a 10.5-mile circumnavigation of the Belgrano Peninsula, Talbot pointed to how the trail contoured the mountainside, swooping in and out of micro-undulations in the terrain to turn users and thus shift their perspective between the snowy, tiger-striped mountains in the distance and glowing grasses in the foreground. “If there isn’t continuous variation in what we’re doing, we tend to lose gratitude for it,” Talbot explained. Changing a user’s picture like this leads to a “continuous renewal of the senses.” Even in places where massive views abound, he’ll shift a hiker’s attention between small, up-close details and grander vistas.

Whimsy, or play, is another element of a well-designed track. When Talbot helped fellow New England trailbuilder Erin Amadon reroute a popular and badly eroded trail in New Hampshire, the pair wove the trail “to every beautiful glacial erratic that we could possibly tie into,” Talbot says, referring to the boulders strewn about the landscape by the prehistoric movement of glaciers. They also anchored turns with rocks so that hikers couldn’t see what was coming around the bend, and in one spot, Talbot used boulders to construct what trailbuilders call a gateway, when a trail threads between two obstacles, like a pair of trees. Gateways make hikers feel as if they’re walking through a portal, passing from one experience to another, says Talbot. Exciting and engaging hikers like this makes them forget they’re even walking a trail. “They think they’re just meandering through the woods,” Amadon says.

Conversely, hikers rebel against a poorly designed trail. On my third day in El Chaltén, I hiked the 14-mile round trip from town to the Laguna de los Tres on my own. For the first time, I noticed ways that the trail influenced my experience. How, for example, the wood-encased steps had an awkward rhythm, as Talbot had pointed out—they were a stride and a half long, instead of one stride—and how hikers had thus flowed like water around them, widening the trail on either side and providing feedback without realizing it. Talbot was also right about the energy shift in the final 1.2 miles, when my scenic hike became a slog. There were beautiful views of the valley below, but my eyes were trained on my feet.

Yet the summit was spectacular, and the hikers nestled among the rocks like concertgoers seemed as satisfied as I felt. The murmur of different languages filled the air as people took selfies, poured maté from thermoses, or just stared at the cracked face of Mount Fitz Roy in quiet contemplation. One young woman was crying.

Talbot, like most trailbuilders, is motivated by a deep love for the outdoors and the belief that it can heal and transform us. He hopes that bringing more of us to wild places will persuade us to save them. “Connecting people with nature could solve a lot of humanity’s problems,” he says.

But a good trail does more than bring people into nature—it protects nature from us. The same hikers who were overcome by the sublime beauty of the lake also told me that, theoretically, they would prefer to walk the steeper, eroded, and more direct trail than a longer but more moderately graded reroute. Some seemed to have misinterpreted what they were experiencing, saying they preferred the “raw” and “natural” character of the existing trail over what they envisioned as a more manicured redesign.

This is a misconception that many hikers have about sustainable trails, and it makes Talbot uncharacteristically irritated. “Anyone who thinks that [that] eroded gully is natural—that’s a human-made travesty,” he tells me as we drive back to El Chaltén from Perito Moreno. “Most people don’t think about trails. They don’t know what’s natural.”

That may be because unsustainable trails still vastly outnumber sustainable ones. While scouting for the Laguna de los Tres redesign one day, we descended a slope adjacent and identical in aspect to the damaged mountainside. This is probably what the mountain originally looked like, Talbot told me. Instead of being brown and rock-strewn like its beleaguered twin, the slope was verdant and fuzzy, blanketed in vegetation. The contrast was startling. We’re so habituated to the sight of our own damage to the land that we don’t even recognize its native state.

After more than a week of tramping through the woods, Talbot and Bittner unlocked a design for a new trail. But it’s unclear when their vision will come to fruition. The project is now facing an obstacle that even the most fastidious designer can’t avoid: politics.

Last March, while Talbot was wrapping up his scouting, community members protested the APN’s construction of a new all-terrain-vehicle trail that led up to the foot of the problematic section he had been tasked to solve. A court has since halted all projects in the area until the APN completes the necessary environmental analysis and public input process.

Even once work is green-lit, the trail faces significant hurdles—namely, funding for construction and labor. Talbot’s redesign sounds “phenomenal,” says professional climber Rolo Garibotti, who led volunteers in a 2008-09 restoration of parts of the trail. But trail work more than anything is hard work, he reminds me, requiring “lots and lots of hands.”

For now, the fate of the embattled upper segment of Laguna de los Tres remains unclear. But having been with Talbot the day he figured out the reroute, I can tell you what the trail could be.

The new track would begin by gently ascending through a forest of old, widely spaced lenga trees. About half a mile in, it’d turn uphill around a small rib in the terrain to reveal a sight that made both Talbot and Bittner laugh in wonder when they found it: a willowy waterfall, framed between a pair of vertical rocks. Here the trail would change tack and ascend gradually back toward the old route, crossing three more waterfalls and emerging from the forest to sweeping views of the valley, where hikers might enjoy that paradoxical comfort of feeling like a small creature in a vast landscape.

At this junction, hikers would probably see the old, eroded trail for years to come. But if this path is built, they could one day make the pilgrimage up to the Laguna de los Tres on a route that no longer tears apart the land. They’d continue to find awe or peace or a sense of accomplishment or whatever else they came for along the way. And the old wound would begin to close, as the mountain slowly heals.

Hit the trails

Best for: Easy access

Talbot built this path in the forested ecological reserve for the Nature Conservancy of Maine. It’s “an accessible trail in a very inaccessible environment,” he says. The 0.7-mile trail has views of Pockwockamus Falls over the west branch of the Penobscot River, with Mount Katahdin in the background.

Round the Mountain Trail, Camden, Maine

Best for: Beginners

Talbot is best known for hand-built trails, but he also uses excavators when they’re appropriate. This multiuse trail in southern Maine was built over three years and “was really showing folks what we can do with specialized and mechanized trail tools,” he says.

Pinturas River Canyon, near Patagonia National Park, Argentina

Best for: Prehistory buffs

Located on an outcrop in the canyon, Cave of the Hands is a UNESCO World Heritage site as it’s home to dozens of 13,000-year-old red, purple, and yellow pictographs. But the landscape isn’t too shabby either: The rushing Pinturas River is flanked by sheer, towering cliffs. Talbot built 30 miles of trails that wind in and out of the basalt plateaus.

Blueberry Ledge and Dicey’s Mill Trails, Mount Whiteface, New Hampshire

Best for: The adventurous

Talbot and his crew spent six seasons performing meticulous rockwork with hand tools. “No hammer, no drills,” he says. It’s “where we made our reputation.” The two trails largely run parallel to one another but are often walked as a loop. Blueberry Ledge has a few scrambly and engaging sections that are better suited for experienced hikers, while Dicey’s Mill offers a more casual day out.