Two Men Set Out To Find Borneo’s Jungle Tribes. One Never Came Back.

A Swiss environmentalist and a Californian art dealer became obsessed with Sarawak, one of the wildest places on Earth. This is their story.

One man was a Swiss environmental activist who wore a loincloth and learned to hunt with a blowpipe before mysteriously disappearing in Sarawak. The other was an art dealer from California who swapped surfing for a life of adventure, travelling deep into the jungles of Borneo in search of the fabulous art of the Dayak people.

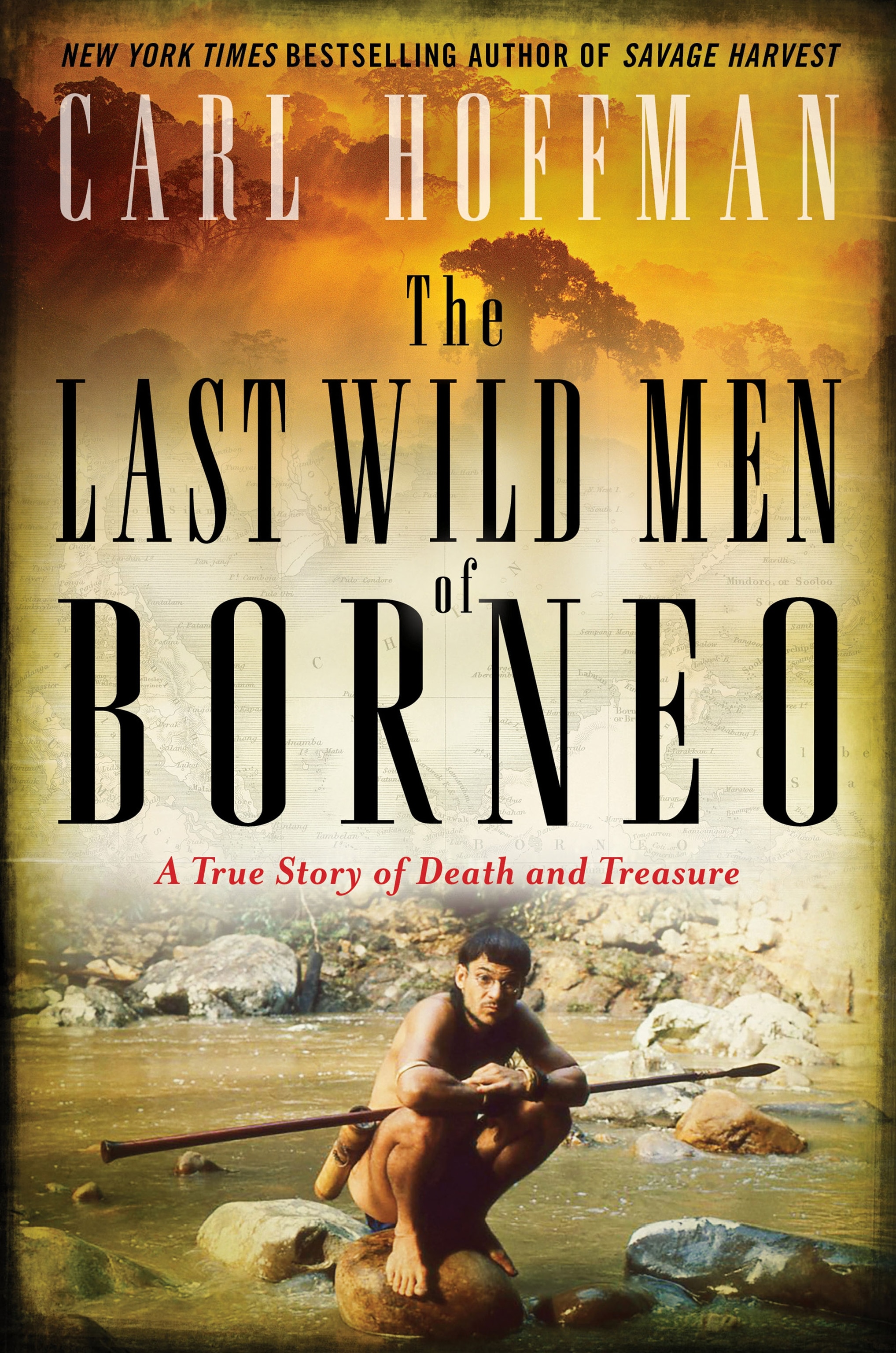

In his new book, The Last Wild Men Of Borneo, author Carl Hoffman brings together the stories of Bruno Manser and Michael Palmieri, two very different, yet similar, men, and their obsession with one of the wildest places on Earth. When National Geographic spoke with Hoffman by phone at his home in Washington, D.C., he explained how Manser became a cult hero in Europe; how Palmieri mapped vast tracts of Borneo by hand; and why palm oil now threatens what remains of the indigenous peoples of Borneo.

The two main characters of your book are a Swiss environmentalist, Bruno Manser, and an American art dealer named Michael Palmieri. Introduce us to these two very different men and explain what drew them to Borneo.

Bruno was born in 1954 and grew up as a classic Baby Boomer during a time of great post-war prosperity. But a lot of things were happening in the 60s, like the hippie movement. The established order was breaking down. As Bruno came of age he was drafted. Every Swiss male must serve in the military, but he refused military service. This resulted in a trial and a prison sentence, which he served for four months. At the end of his prison sentence, he marched off into the high Alps, first to herd cows and make cheese, and then to become a shepherd. This was an apprenticeship in a way, living a life of great beauty, hardship, and isolation up in the Swiss mountains.

But he wanted to go further. He wanted no association with the culture of commerce, to avoid money, and to make everything himself. He flew to Thailand, spent six months wandering through Southeast Asia, then surreptitiously joined a British caving expedition in the Mulu caves in Sarawak. From there, he set out into the wilderness looking for the Penan.

Michael was bit older and had grown up as the anti-Vietnam War movement was starting. He was a surfer boy, not an intellectual in the way Bruno was. In 1964, he got the call for the draft. He said, “Forget it,” headed south to Mexico, then across the Atlantic on a freighter. He spent 10 years in Europe before making his way to Bali and Borneo.

Even though he and Bruno were very different men, they were also very similar. Michael obviously had a more mercenary purpose than Bruno, but he didn’t go into Borneo thinking, “Oh, this is how I’m gonna get rich!” He went into Borneo because he was obsessed with the tribal people and the magic of their world. He wanted to see it and have adventure.

Manser devoted his life to the Penan people of Sarawak. Take us inside their world and explain how Manser immersed himself in their culture.

The Penan were nomads who lived deep in the forest, moving every few weeks, depending on the food situation, building temporary structures and living in small, mostly family bands, hunting and gathering in the forest. Bruno didn’t really know where he was going, or what he was doing. But after 10 days of trekking through the jungle, he found the Penan and insinuated himself into their world. Over weeks and months, they began to accept him, and he quickly learned to speak Penan. He did everything he could to shed his Western ways. He walked barefoot through the jungle and hunted as they did.

The irony is that Bruno attempted to become more Penan than the Penan themselves! He had an idealistic vision of their lives and an ahistorical view of the Penan as people who had been living without contact forever. That wasn’t completely true. The Penan were starting to wear T-shirts and sneakers, like people all over the world, cut their hair shorter, and wear watches. While they were doing that, Bruno was trying to make a birch-bark loincloth and growing his hair in the traditional mullet style of the Penan.

For their part, the Penan looked at Bruno as a brother and soul mate, in a way. But they also always looked at him as what he was: a white person who had a power they didn’t have. To Bruno, the Penan were these untouched people. But to the Penan, Bruno represented something powerful from their historical past: the British. The era of the White Rajah was for the Penan one of great safety, when the government protected them from their neighbors, the Dayak, who were violent and much more sophisticated. So they looked at Bruno as this representative of a golden age of white power. That’s an incredibly interesting and ironic thing!

In Borneo, you say Palmieri, “wasn’t just travelling to a remote physical location, but to a metaphysical one—the rich spiritual world of the Dayaks.” Tell us about their culture and art.

The Dayaks of Borneo have this incredibly rich, high culture that was influenced by many different places for a thousand years. Everything they touched, they made beautiful! They painted, they carved, they made spectacular things with beads. Their art was a reflection of their spiritual world, in which the tree of life is the central icon, representing death, life, and the ancestors. Unlike modern monotheism, where you’re alive and then you die and they’re two totally different places, for the Dayak these worlds are happening simultaneously, in a constant ceremonial and spiritual attempt to placate the spirits. That resulted in all kinds of rich ceremony, particularly surrounding death and the rice harvest, and this inspired the great art that Michael coveted.

Former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown called the deforestation of Sarawak “one of the greatest environmental crimes in history.” Give us a picture of the destruction and how it affected the Penan.

There had been logging in Sarawak for a long time. But it was mostly slow and piecemeal. After Malaysia’s independence, the political structure changed and local Sarawak politicians, of whom Abdul Taib Mahmud became preeminent, began creating wholesale logging concessions, which largely went to their friends and family. As a result, the pace of logging accelerated hugely, particularly in the 70s and 80s.

Coinciding with Bruno’s arrival in Sarawak, in 1984, logging began pushing into the traditional lands of the Eastern Penan and the Dayak. The Dayak had villages and ancestral lands they could bargain over in terms of compensation, even though that compensation was ridiculously small. But the Penan had nothing. In Penan consciousness, all of the land was theirs and their ancestors were buried throughout the forest. Every stream, hill, and tree had meaning. But to the government of Malaysia, the Penan were the lowest of the low. The Muslim majority and Chinese looked down on the Dayaks, and the Dayaks looked down on the Penan. Logging destroyed their whole world.

Many of the artworks Palmieri bought, sometimes in dubious circumstances, ended up in prestigious art museums. Give us a flavor of his adventures and discuss the ethics of that trade.

I take some issue with the word “dubious.” In some ways it was dubious, in the sense that the Dayaks themselves, from whom Michael purchased the art, didn’t have an understanding of its value outside of Borneo. But Michael bought and traded at what the Dayaks believed was a fair price—so there are a lot of grey ethical issues around this.

He didn’t just go in for a couple weeks here and there. Over a 10-year period, Michael went in for months at a time and built these incredible networks. Borneo is a massive place—the third-largest island in the world. At that time it was a vast, wild jungle with river rapids and mountains. Michael would go up a river for weeks at a time and walk to very remote places that had had little outside contact. He even bought a traditional, Mahakam River freighter. It was 100 feet long, with a crew, like a backwoods tractor-trailer. Michael lived on the boat, ranging for weeks at a time through the river systems.

One day when I visited him in Borneo, he said, “Let me show you something.” We went into his bedroom, he lifted up the mattress and pulled out this huge pile of 2 x 3 foot pieces of poster board, on which he had drawn the most intricate, beautiful maps: every village and set of rapids and branch of a river, through a huge swath of the third-largest island in the world. He had been to all those places and mapped them out.

Manser eventually became both a wanted man and a global media star. Tell us about that period in his life and how he then vanished in 2000. Some say he was murdered. Will we ever know what happened to him?

Bruno became the most wanted man in Malaysia. To the Malaysians, he represented not just this guy making trouble with the Penan, but the personification of the White Rajah’s return. He was arrested twice, escaped both times under gunfire—crazy stories that seem too wild to believe! Back in Europe, the movement to save the Penan was growing larger. His parents were getting old, his father had cancer. Bruno was bitten by a pit viper snake and almost died.

His best friend, Georges Ruegg, was sent to extract him, which he did, using false papers and disguises, like false colored contact lenses. When Bruno emerged, he was lionized as a sort of Tarzan who fulfilled every white trope of the jungle man. In many ways, people were less interested in the Penan than in Bruno himself—this guy who hunted with a blowpipe and wore a loincloth, but who could speak impeccable Swiss-German at a dinner party. People described him like Jesus!

Despite Bruno’s narrow escape from Sarawak, he started sneaking back in and out. But over the next 10 years, despite ever more daring actions—from chaining himself to flagpoles to hunger strikes—he had no success. He was trying to stop logging in Sarawak, but that never happened. And over time that drove Bruno into a sort of madness. He found himself in a dead end from which he could not escape. When he went to Borneo in 2000, he wrote strange notes and everyone had the feeling that he wasn’t coming back.

His loyal followers and family tend to want to believe that Bruno was killed by Malaysian security personnel, or loggers in the pay of the Malaysian government. But the reality appears to be that he essentially committed suicide. Not by hanging himself or slitting his wrists, but by living so close to the edge. He went deep into the forest and never came out.

The book ends on a plaintive note. The Penan have been forced into settlements, Manser is dead, Palmieri disillusioned. Is the age of Borneo’s wild men over? Can something still be saved of the rainforest? What can our readers do?

It’s a really good question! To a large extent, the Borneo that Manser wanted to save, and that Michael explored, is gone. Palm oil is now taking over vast tracts of Borneo.

What can readers do? I’m not sure what they can do, apart from not buying palm oil products. People also need to think about their own values, whether stuff is more important than culture. But these things are not black and white. There are now generations of Dayaks and Penan who are educated and enjoying the fruits of development. For people like me, and Bruno, those are negatives. But we’re rich, privileged, white Westerners. So maybe we can’t always judge.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.