Pictures: Fish Light Up in Neon Colors

Camouflaged fish light up in neon hues when hit with blue light.

Coral reefs are full of flamboyantly colored creatures. But a new study finds that even the more subtly hued camouflaged species hiding in nooks and crannies have their gaudy side. You just have to know how to look at them.

Some 180 species of fish and sharks have unique structures in their skin that enable them to glow neon red, green, and orange under blue light—a process known as biofluorescence.

Unlike bioluminescence—a phenomenon whereby organisms produce their own light by way of a chemical reaction or harbor bacteria that produce the light for them—biofluorescence is a passive process that animals can't turn off and on. (Learn more about the difference between biofluorescence and bioluminescence.)

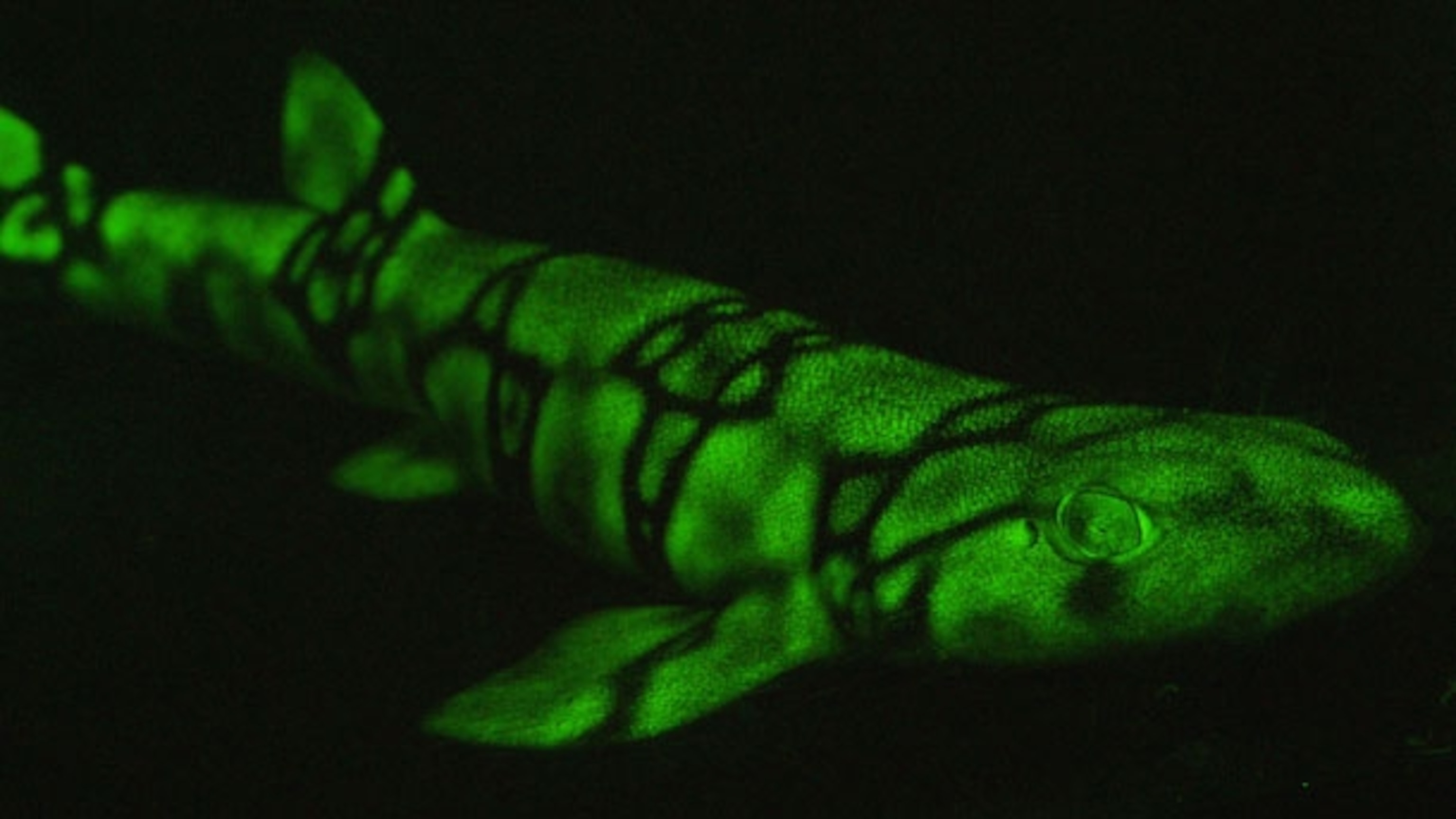

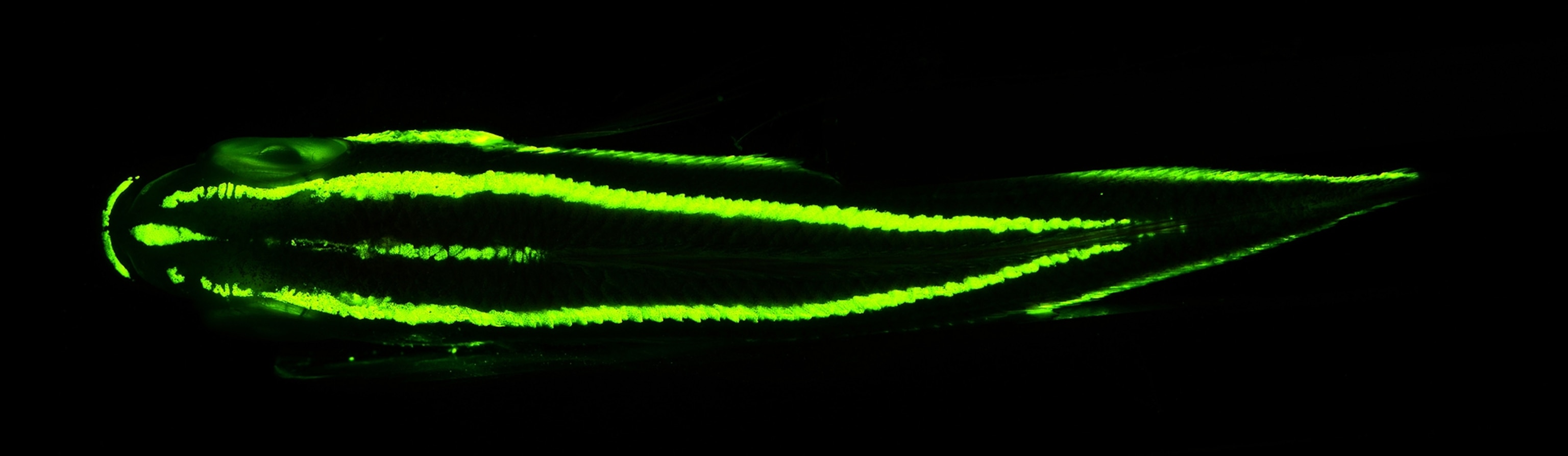

Biofluorescent animals constantly absorb blue light and re-emit it as different colors, like the brilliant green of the deep-sea-dwelling chain catshark (Scyliorhinus retifer) above. But in the absence of a yellow filter to block out the blue, the neon colors are invisible. Researchers found that some biofluorescent fish do, in fact, have green-yellow filters in their eyes, presumably for just this purpose.

"We were completely surprised to find how widespread [this ability] was," said David Gruber, a marine molecular biologist at City University of New York. "And it was most widespread in cryptic fishes," he said.

Gruber, a National Geographic grantee, and colleagues published their findings online January 8 in the journal PLOS ONE.

People don't really think about the importance of light in these environments, said study co-author John Sparks, curator of fishes at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Only a small portion of the ocean is lit by the sun, he said, so animals rely on other ways of generating light to communicate with each other.

The fact that this ability is so widespread across so many fish and shark species "tells us organisms are using light in ways we don't even see," Sparks noted.

"It's a hidden world that we're just now beginning to tune into," said Gruber.

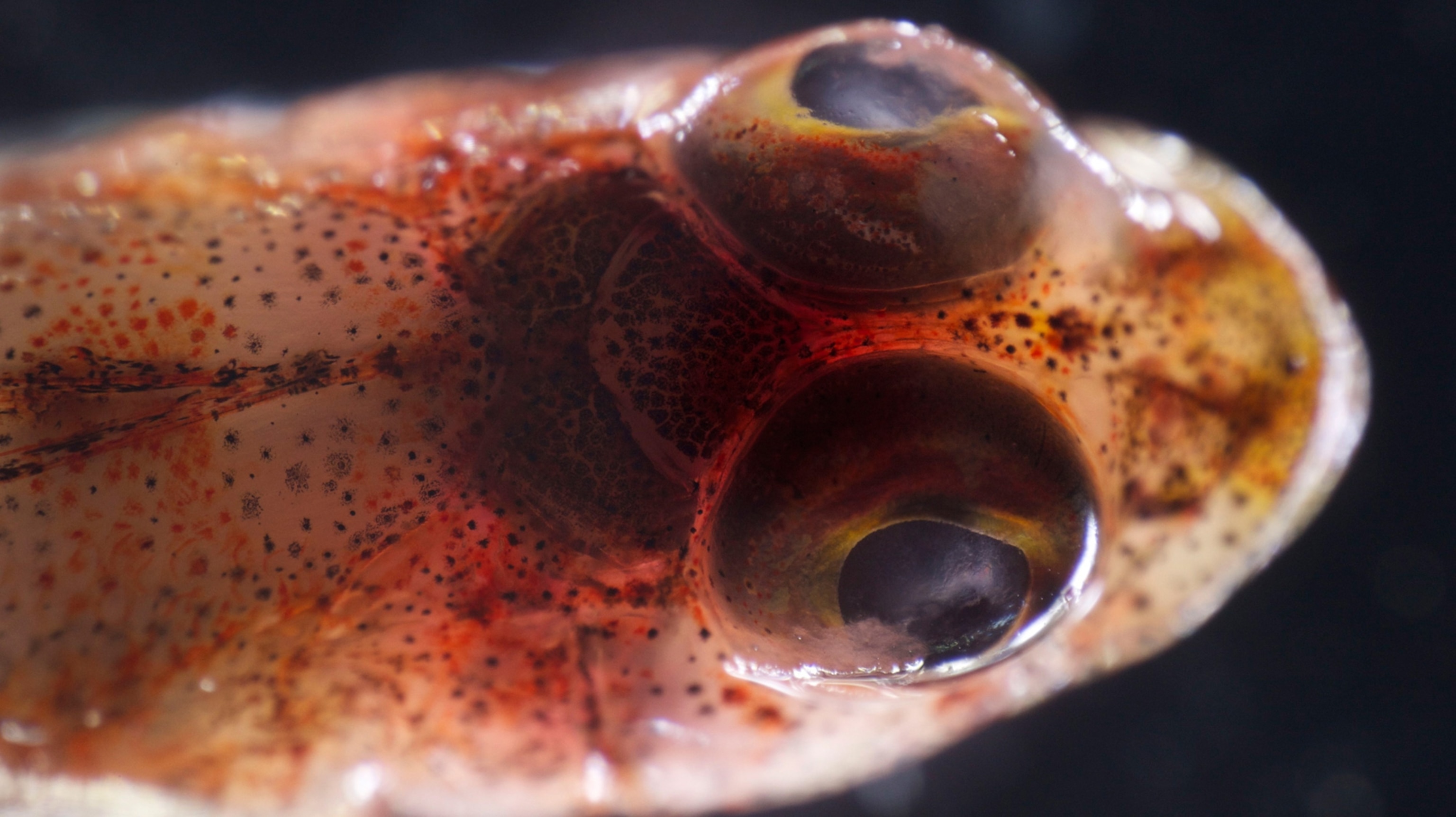

Triplefin Blennie

Gruber and Sparks are no strangers to glowing marine creatures. Their previous work culminated in a bioluminescent display at the American Museum of Natural History from March 2012 to January 2013.

Their interest in biofluorescent fish was sparked by a green eel who happened to swim into a photo Gruber and Sparks were taking of a biofluorescent coral wall for the museum exhibit. Gruber was looking at the fluorescent coral when he noticed there was also a fluorescent fish.

"We were photobombed by a green eel," said Gruber.

They went to look at the eel in the wild, and soon discovered that all these other fish species, including the triplefin blennie above, were also biofluorescent.

Ribbon of Green

Gruber and Sparks speculate that fish fluorescence is a way for the fish to communicate within and between species.

"The ones that are biofluorescent are [mostly] the cryptically colored fish," said Sparks. To an organism that can visualize it, "these fish must stick out like a sore thumb."

The different patterns and colors of fluorescent light would be a good way of communicating secretly, since only organisms with a yellow filter in their eyes could see the flamboyant colors.

The shortfin false moray eel (Kaupichthys brachychirus) above may look unassuming under normal lighting conditions, but put it under a blue light, photograph it with a yellow filter, and it lights up like a glow stick.

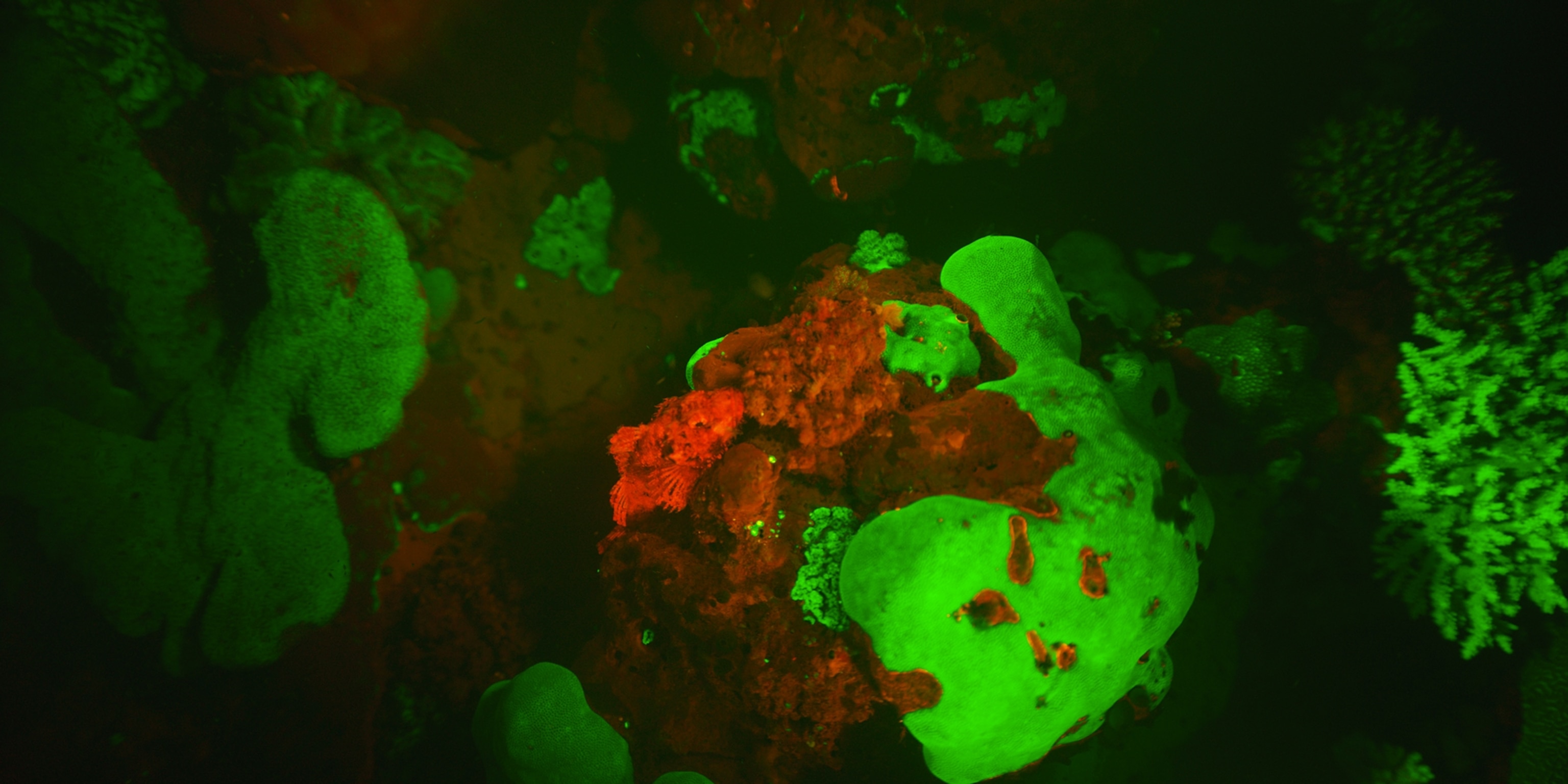

Red Light

There have been many anecdotal reports that fish can fluoresce, said Edith Widder, senior scientist at the Ocean Research and Conservation Association in Fort Pierce, Florida.

A few papers mentioned red fluorescence, such as that seen in the scorpionfish above. But nothing pulled together evidence from so many different fish species.

To see a formal paper putting it all together and suggesting the widespread nature of biofluorescence makes Widder happy.

"It gives [biofluorescence] a lot more credence as a phenomenon that has adaptive value," said Widder, who was not involved in the study. Being able to communicate privately is "hugely valuable," she added.

It could enable individuals of one species to signal to each other without making themselves vulnerable to predators or competitors.

Neon Hide-and-Seek

Of course, fish aren't the only ones that fluoresce. So even if an animal lit up like a stoplight—like the scorpionfish above—it could still manage to blend in with the glowing corals and algae around it. (Watch a video about coral reefs that glow in the dark.)

Nico Michiels, a marine biologist at the University of Tuebingen in Germany, also studies biofluorescence in fish, but has concentrated on those that give off red light rather than green. Though he wasn’t involved in the study, he's excited about its findings. "[It's] setting the scene."

Now, he'd love to know the intensity of flourescence in the fish that Gruber and Sparks studied. This ability is a continuum that ranges from "virtually nothing—where we have difficulty deciding whether it's fluorescence or not—up to where it's glowing like hell," Michiels said. Knowing that could help figure out the function.

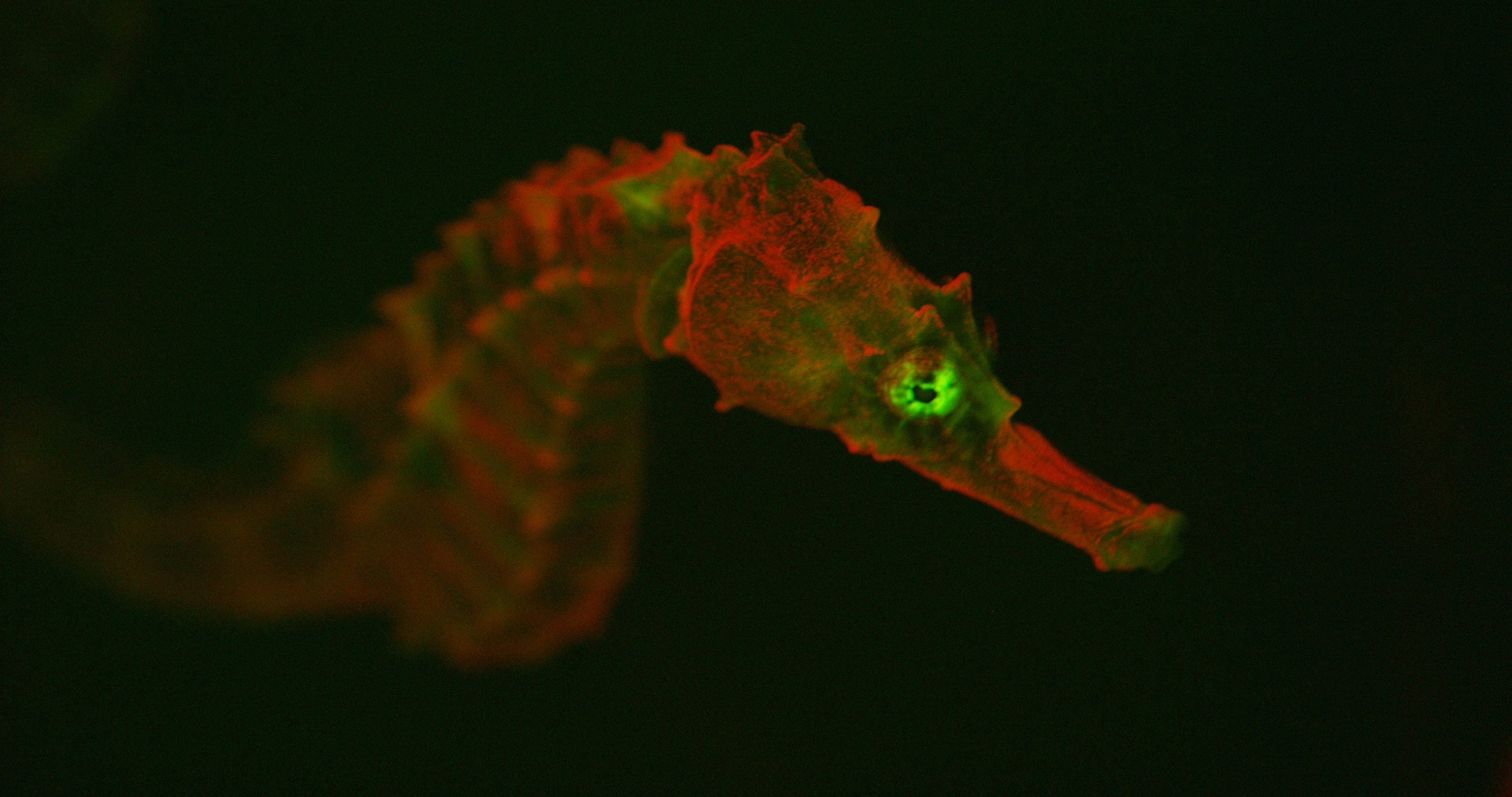

Glowing Seahorse

Some species even give off more than one color of fluorescent light. This seahorse (Hippocampus erectus) glows mostly red with green highlights concentrated around its eye.

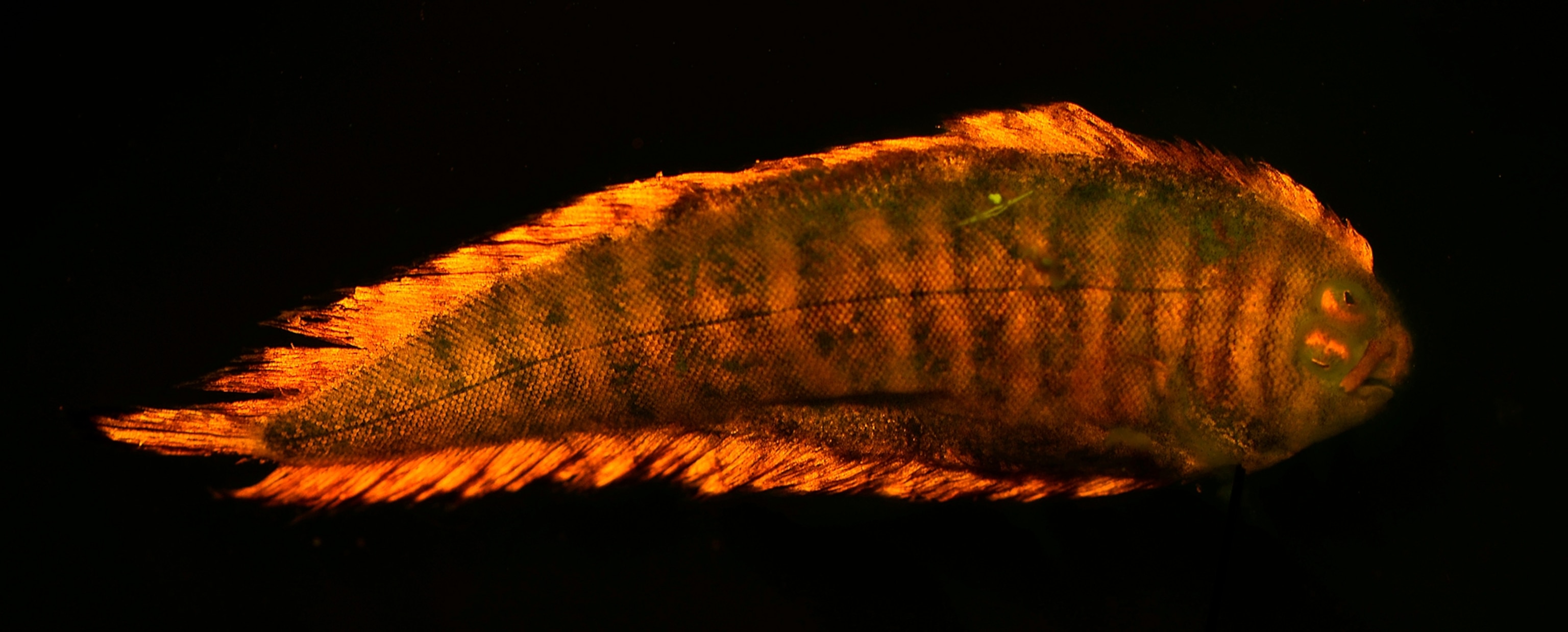

Flatfish

Then there are species, like this flatfish, that have it both ways. They display mainly red fluorescence patterns on their back (shown) and green fluorescence patterns on their belly.

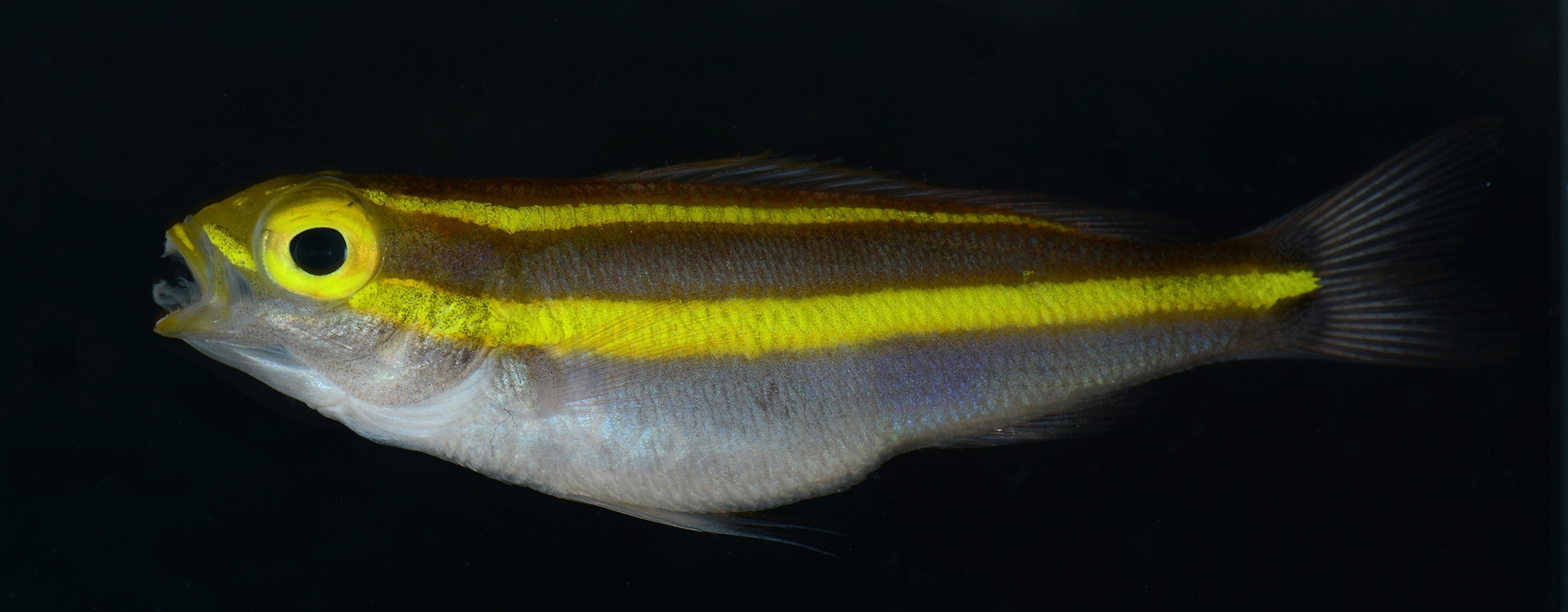

Bream

The yellow stripes running down the side of this bream as seen in normal lighting are reminiscent of racing stripes. But when seen from the top while fluorescing (pictured below), those yellow stripes glow green.

Researchers will need to do more work before they can pin down the functions behind fish fluorescence patterns.

Follow Jane J. Lee on Twitter .