Weird Animal Question of the Week: How Do You Collar Wild Animals?

From mountain lions to wolves to snakes, see how scientists capture and tag wildlife.

If you think your job is nerve-wracking, try putting a collar on a mountain lion.

Wildlife biologist Dennis Jorgensen was high up in a tree in Montana in 2009 trying to bring down a tranquilized mountain lion, when the still-awake animal took a sudden swipe at his face.

"My job was to make sure the cat didn't fall. We both made it out safe," he said, adding that collaring can be "risky business."

Jorgensen, who has collared animals ranging from big cats to reptiles as part of his work with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Northern Great Plains program, said tagging technology is becoming more advanced and efficient, "opening up opportunities for understanding a broader variety of wildlife."

Collaring and tagging wildlife is the theme of today's Weird Animal Question of the Week, inspired by Julie Hirschfeld from northern Michigan. Julie asked, "How does one collar a wolf?" on a blog post by National Geographic explorer Jay Simpson about his adventures in tracking a lone wolf in Oregon.

Jorgensen hasn't collared wolves, but he said some "general approaches translate across species."

Following In Their Footsteps

He explained that scientists capture wolves and other species by baiting padded leg-hold traps, pain-free apparatuses that are intended to hold them for a short time and are checked frequently.

Federal biologists also use leg-hold traps to trap, tranquilize, and then place a collar on a wolf, according to Simpson.

When targeting mountain lions, scientists will sometimes use trained dogs to send the animal up a tree-sometimes as much as 40 feet (12 meters) high-before they shoot the treed animal with a tranquilizer dart.

Once the collaring is done, the animal is given an injection to reverse the effects of the tranquilizer more quickly, though it is still "groggy," Jorgensen said. (Read more about mountain lions in National Geographic magazine.)

Why all this effort? By collaring animals, scientists can suss out how animals use their habitat: what areas they prefer, whether environmental changes alter their behavior, and how they travel. (Learn about National Geographic's work tracking animals with the Crittercam.)

In one case, a collared mountain lion moved from the Black Hills of South Dakota all the way to New York State, Jorgensen said, which shows that big animals "are able to move through populated areas without us knowing it."

Learning how animals use their landscape can also help scientists figure out how to reduce conflicts between animals and people, he added.

Birds and Snakes

There are many different types of collars and tags, depending on the species.

Some are literally collars, which are outfitted with electronics and weights to make sure they sit properly on the animals' necks.

On some grassland birds, such as long-billed curlews, Jorgensen and colleagues have used a satellite tag "about the size of a Kit Kat bar" that attached "like a backpack," with Teflon bands that wrap around the bird's thighs to avoid hindering its movement.

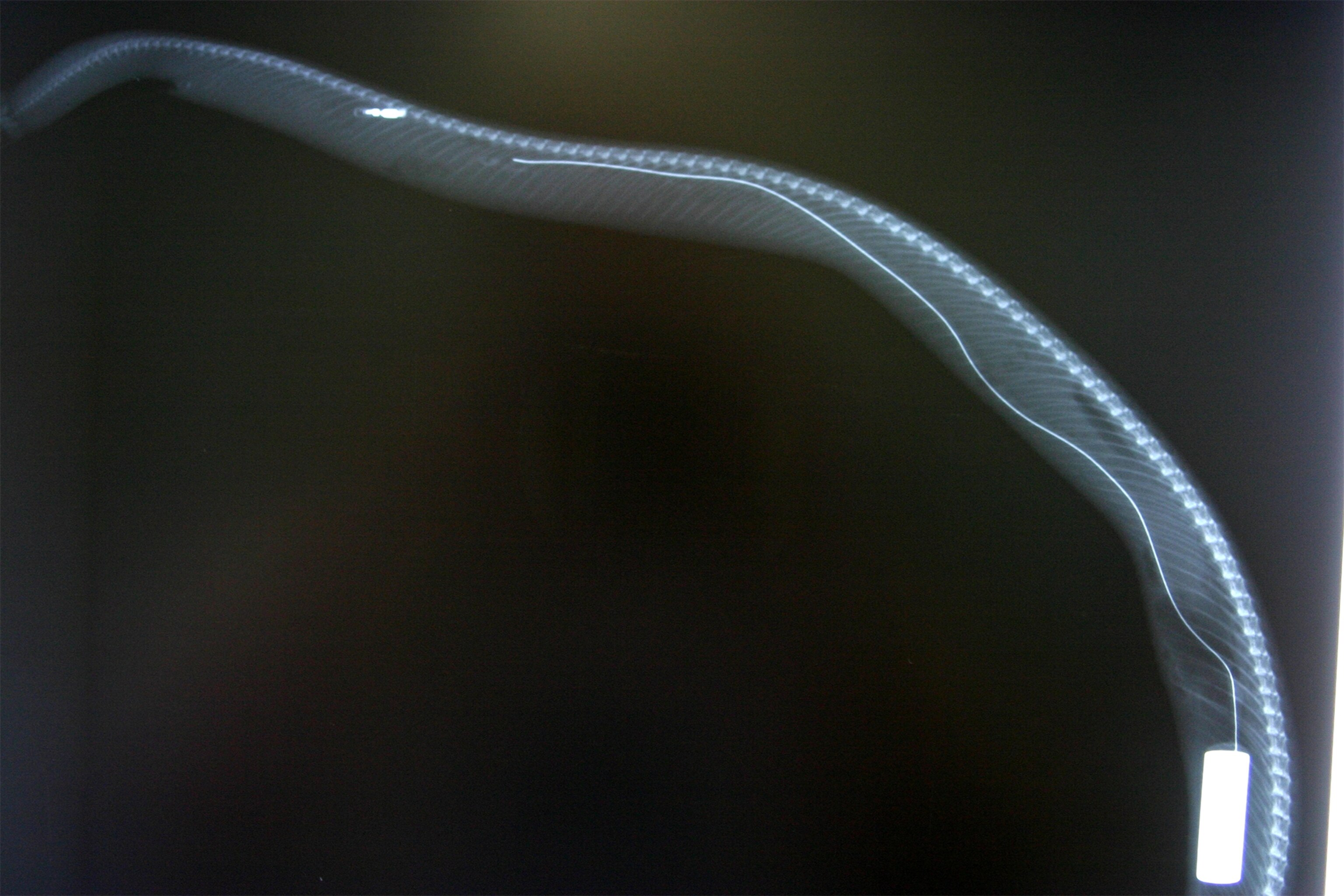

When you don't have a neck, though, collaring can be tough.

To study prairie rattlesnakes in Alberta, Canada, for instance, Jorgensen sets up traps around their winter dens. (See National Geographic's rattlesnake pictures.)

Once the reptiles are captured, the scientists implant a radio tag "smaller than a baby mouse" in the snake's body cavity; the device is covered with beeswax, a material the body doesn't reject.

New Frontiers

Tagging technology is even starting to take advantage of social media. Some sharks in Australia, for example, are essentially on Twitter: Western Australia's Department of Fisheries staff have implanted some of the fish with transmitters that alert the social media website when they are near a beach, so swimmers are alerted to their presence.

In the same vein, the WWF plans to put cellular-based collars on several bison in Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan. If one of the animals roams onto private lands, for instance, the collar will sent a text message to scientists. (Related: "How to Put a Camera on a 1,000-Pound Bison.")

"The bison's collar can send a message to say, 'I'm on XYZ's property right now. He doesn't want me here. Can you bring me back to the park?'" Jorgensen said.

Jorgensen is excited about the quest for ever better ways to track wildlife, calling it a "new frontier" in communication. But he's also concerned that the ability to track animals from afar can separate scientists from the very animals and habitats they're studying.

In the field, you truly "develop this interest in the animal [because] you're in its habitat every day."

Next week is National Bat Week, October 26 to November 1. Got any bat myths you want investigated? Tweet me, follow me on Facebook, or leave a comment below.