How A Family-Run Oyster Business Caused A National Ruckus

When the oyster farm, located in a national wilderness area, was closed, contentious debate erupted and divided a community.

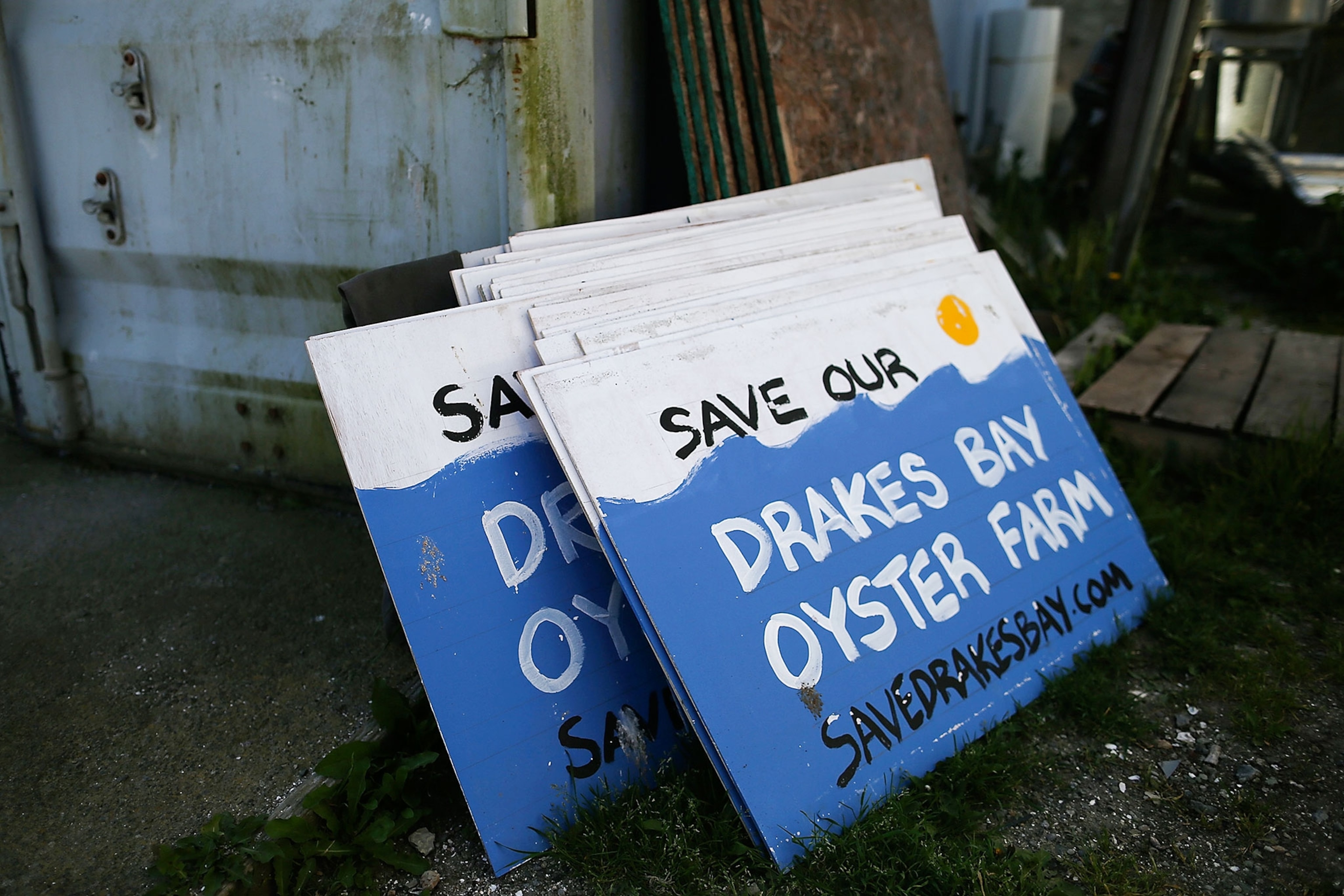

Drakes Bay Oyster Company was a small family-run operation in Marin County, California. But when it was ordered closed because it was inside the Point Reyes National Seashore boundaries, what had been a local story went national. Communities divided; friends fell out. Eventually, the acrimonious debate drew in politicians, lobbyists and pressure groups from all over America.

Summer Brennan, author of The Oyster War: The True Story of A Small Farm, Big Politics And The Future of Wilderness In America had grown up near Point Reyes and when the editor of the local paper offered her a job, she moved home from Brooklyn. As she delved deeper into the story she had to face powerful opponents as well as her own biases.

Talking from Brooklyn, (she returned there after writing the book), she describes how the American author and journalist Jack London became involved with the oyster pirates of the Gold Rush era; how the Koch Brothers galvanized the debate; and why the meaning of wilderness was at the heart of the battle.

You were living in New York when the story about a disputed oyster farm in a remote part of California broke. What drew you to it?

I’m from the area where the story happened, near the Point Reyes National Seashore. In early 2012, I was working on some freelance writing ideas and thought it would be cool to do some environmental stories about where I grew up. So I got in touch with my old hometown newspaper, The Point Reyes Light because I was impressed by some of the recent stories I’d seen. I asked if they took freelance pieces.

The issue was that this farm was inside a designated wilderness area, grandfathered in because it pre-dated the wilderness area.Summer Brennan

Instead, the editor offered me a full time job as their staff reporter. That’s when I found out about this conflict, which was the key issue they were covering. I was immediately struck by how passionate everyone involved with this story was. And I wanted to understand where that passion was coming from. I’ve worked with international organizations and in actual military conflicts, but I’ve rarely seen people get quite so worked up. I felt there must be something important about this issue if people were so involved.

Give us a picture of the oyster farm at the heart of this battle. It wasn’t exactly an aluminium smelting plant, was it?

[Laughs] The Drakes Bay Oyster Company was very modest-looking. It had been family run, and in 2004 the family who owned sold it to a ranching family next door. The farm consists of about one and a half acres of mobile homes for farm workers, a shop for the [sale of] oysters, a processing plant, and a cannery in a converted shipping container. Physically, it was small.

In most places, like here on Long Island where I live, they are scrambling to reintroduce oysters. Why were they viewed so negatively in northern California?

The oysters themselves weren’t viewed negatively. There are other oyster farms in this area. The issue was that this farm was inside a designated wilderness area, grandfathered in because it pre-dated the wilderness area. There was not meant to be any kind of commercial operation inside a wilderness area. That was decided in 1976. You can disagree about whether that was the right thing to do. But it didn’t have to do with oysters themselves.

You write “oysters have been a source of conflict since America was founded.” Tell us about the oyster pirates of the Gold Rush era and how Jack London came to be involved.

Jack London claims that in his late teens he bought a sloop from an oyster pirate in San Francisco and tried his hand at oyster pirating himself. He ended up getting a job with the official fish patrol that monitored the bay. It was like a Wild West of the waves in San Francisco Bay. A mass of immigrants was coming from all over America and other countries and they were overfishing the bay. The patrol was there to protect fish stocks. Jack London became a deputy on the fish patrol, making money by trying to arrest oyster pirates.

The story was like a Rorschach inkblot test. People saw within it their own fears and prejudices.Summer Brennan

The oyster pirates were a real mix of people. Some were notoriously nasty characters. By the time Jack London is writing about this, in the 1880s, after the Gold Rush, the oyster industry in San Francisco Bay had already been established by the Morgan Oyster Company. Oystering was big business. The oyster pirates would launch attacks with as many as 50 pirates because the oyster companies were guarded and well armed.

The battle over this oyster farm caused a huge ruckus in Marin County. Why should we care?

[Laughs] People did care and that’s what I found fascinating. The story was like a Rorschach inkblot test. People saw within it their own fears and prejudices. Some saw a story about big government harassing the little guy. Other people saw conservatives doing a land grab for public lands to the detriment of the environment. Others saw it as a story about bad science.

One of the reasons it became such an issue locally was because it is about encroachment. We feel we’re running out of space and the space we have is precious. Who decides what uses it should be put to? Should it go to hikers and kayakers? Or are we going to make space for the little guy to have a family farm? There’s a lot of anxiety about these issues.

You write that one of the themes of the book is “what it means to be wild.” Unpack that idea for us.

It was fascinating to see how much debate there was on what a wilderness should be. There isn’t a clear definition. What is wilderness? What does wild mean?

It was fascinating to see how much debate there was on what a wilderness should be. There isn’t a clear definition. What is wilderness? What does wild mean?Summer Brennan

We live in an increasingly tamed world. Many wild places in the United States don’t have intact ecosystems; they’re full of non-native species, from larger animals to tiny plants. Is it wild because it’s far away? Or because it hasn’t been adulterated with outside forces? The legal definition of wilderness is very poetic, “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammelled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” But what does that mean? What does ‘remain’ mean?

The battle over this small oyster farm divided a community, broke up friendships, and eventually drew in the Koch Brothers’ attorneys and D.C. lobbyists. Is this a reflection of the increasingly shrill and partisan nature of public discourse in America?

Is that new? I don’t know. Compromise is hard and confusing. This issue wasn’t an easy divide that was familiar to people. It wasn’t a Republican versus Democrat story. That’s why the factions were often referred to as “strange bedfellows.”

You had people who were Sierra Club members, who voted in line with their values. But then they would see that Michael Pollan was writing about the other side. So they would get confused. In general, it’s easier to get outraged about a lot of issues than to get educated.

To overturn a wilderness designation would be very useful to people like the Koch Brothers. They would very much like there to be no private land for environmental protection. The group that got involved with the oyster farm was Cause For Action. It may have specifically been formed to help the oyster farm, because it happened at the same time, though I don’t have any proof of that.

The Koch Brothers have been funding these kinds of groups all over the country but they don’t want people to know that they are funding and staffing them with people they train in their own institute. But that’s what they do. That’s who Cause of Action was. People in the community were very upset. They were going around saying, “You’re a Koch Brothers supporter!” “No, YOU’RE a Koch Brothers supporter!” “How dare you say that to me!” —as though somebody was saying something uncharitable about your mother.

I couldn’t help feeling rather sorry for the Lunny family, who owned the Drakes Bay Oyster Company. Where did your sympathies lie?

I was very sympathetic to them. They are well known in the community. Their family first came out to West Marin in the 1940s as ranchers. I felt bad because it was clear they really believed in their cause. It’s sad for them, but fortunately they have other businesses. They also had so much public support and financial support. I understand the emotion they went through. But, much as I hate to say it, in the end I felt they were gamblers more than victims. They hoped they could get it to work out and it didn’t.

You say at the end of the book, “The story I have written is not the story I thought I would find when I set out.” Explain that and the lessons you learned.

I went into this having been told, for instance, that oysters were plentifully native to the Bay Area. And that even though the oysters that were being farmed at Drakes Bay were non-native, they were supplementing an important natural ecosystem. To remove them might be detrimental to the environment.

But that’s not true. I was told a lot of other things that made it sound like there was a conspiracy against the oyster farm, and that it might be environmentally dangerous to remove it.

I liked Kevin Lunny. I interviewed him when I was a reporter at the paper and I met his sister, Ginny, a number of times. I assumed I would be sympathetic to them. So I was surprised when the arguments for allowing the farm to stay didn’t check out. I was a bit nervous about it too, because I know that powerful people are invested in this story.

But you can’t take things for granted just because you see it on the Internet! You read a new story: Oysters are native to the Bay Area and you say, OK cool, and accept it. So it was an interesting lesson about how history isn’t always as we believe it to be. It’s selective.

I also thought so much about what bias means because that was an issue that came up a lot. Everybody was thinking I was biased, no matter what side they were on. So I had to think, what is bias? What are my biases and how might they be coloring this? It was fascinating to see why we tell – and believe - certain stories, more than others.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter.