As Ringling Ends Circus, See Where Its Elephants Retired

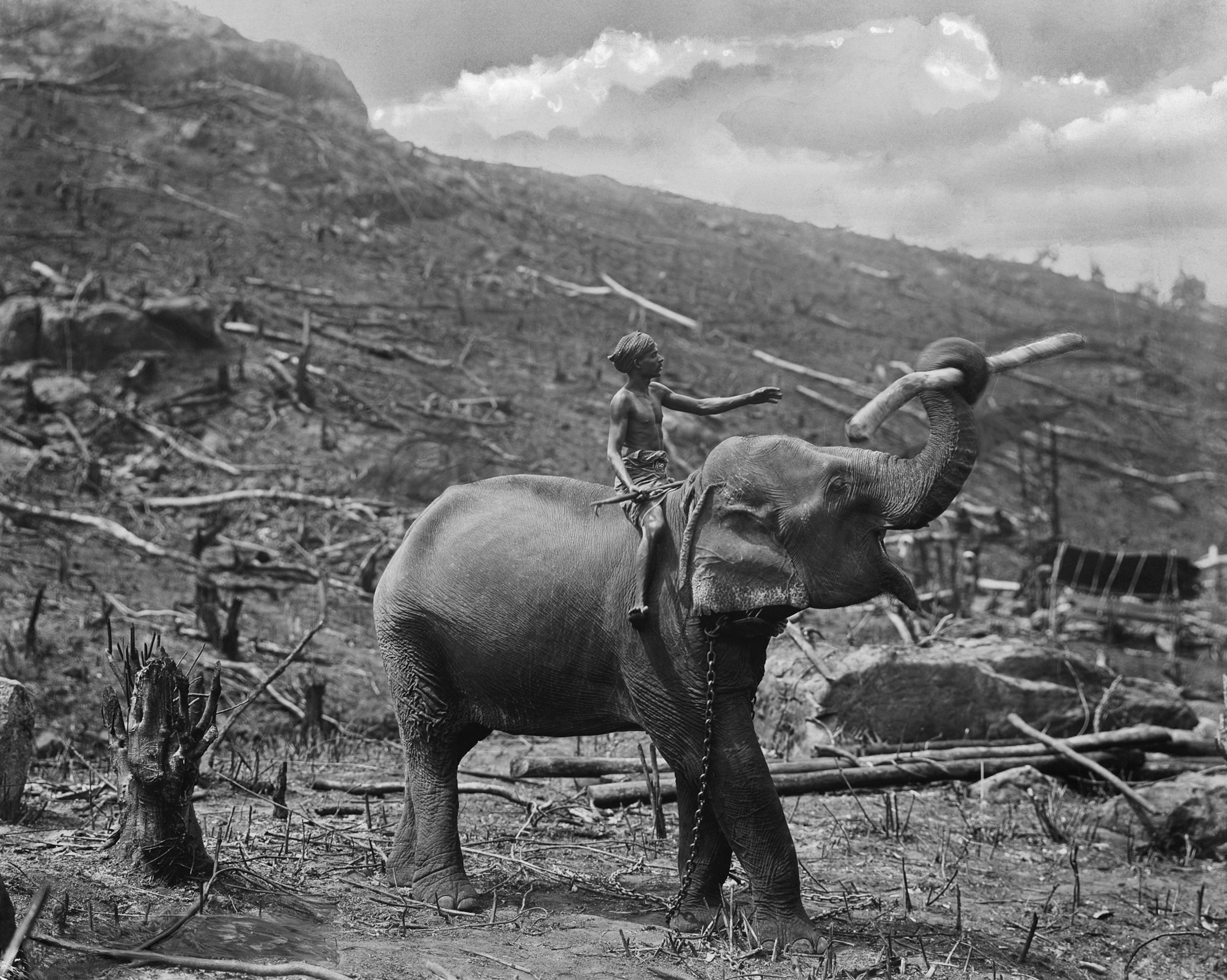

The circus has sent its elephants to the remote 300-acre site, and announced its closure in early 2017.

POLK CITY, Florida — Beneath a sky of clotted clouds, in a verdant pasture, a man squats at the foot of an old elephant to give her a pedicure.

With a heavy metal file David Polk shaves and shapes her horny nails, five on each front foot, four in the back. With a small curved knife he scrapes gunk from beneath her brittle cuticles—the only spot where an elephant sweats—and trims them back. Says Polk, "Old ladies' cuticles are like old men's hair. They grow in every direction."

Baby is her name. Until her retirement some months ago, she performed for Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus for most of the past 46 years. In recent years she'd traveled 18,000 miles for shows in 45 cities until she was literally put out to pasture because, her handlers say, she just wasn't herself anymore.

On this day she meekly places one foot after the other on Polk's blue metal stool, responding to his murmured command—"foot"—and to the touch of a tool he calls a guide, but is also known as a bull hook, or ankus. When Polk strolls to an electric fence to talk with me, Baby follows wearily. Her eyelids sag. Her skin has faded into a mass of freckles. Her huge ears are frayed, like a flag left too long in the weather.

At 54 years old, Baby is the most recent retiree to this dusty spot in central Florida. She will live out her days with 29 other elephants at Ringling's Center for Elephant Conservation, a 200-acre ranch established 20 years ago. Not all the animals here are tired and old. Most are active in the reproduction ring, producing baby Asian elephants that, until recently, were destined to be stars in "The Greatest Show on Earth."

Elephants Quit the Circus

In early March, the peace of this place was briefly broken. The skies above rattled with news helicopters seeking panoramas after Ringling CEO Kenneth Feld announced he was releasing all performing pachyderms from the 145-year-old circus, which he likes to brag is "one year older than baseball." Within three years, he said, all 13 performers would be moved to this Florida compound.

His decision will create the largest concentration of Asian elephants in the Western Hemisphere. An endangered species, they are the second largest mammal on land, behind the African elephant. The World Wildlife Fund estimated last year that about 32,000 Asian elephants remain, with about 250 in the U.S., most at zoos. No more will arrive here: An international treaty has prohibited trade in Asian elephants—the ones used in circuses—since 1975.

Just 15 miles from the crowds and chaos of Walt Disney World, Ringling's elephant village is on no tourist's map. Its drive is unmarked except for two red signs: "No Trespassing." Animals can't be seen from the road.

Here an elephant's life is routine. Food, water, and daily baths are the highlights. No lights swirl, no music blasts. These elephants lower their huge bodies to the ground whenever they want, not at the command of handlers. Nor do children force them to lumber awkwardly to their feet by shouting, at the ringmaster's command, "WAKE UP, ELEPHANTS!"

We're in the entertainment business. It takes away from the total enjoyment when you're getting yelled at, and your kids are getting yelled at, by these activists.Kenneth Feld, CEO, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey

Ringling's announcement cheered animal rights groups that for years have accused it and other circuses of abusing elephants, not only with bull hooks but also by requiring them to perform too often—about 190 days a year—and by making them travel too far in cramped trucks or train cars. To make their case, activists picketed circuses. They shouted at parents and children. They sued. And cities and towns responded, banning the bull hook and leading Ringling to cross those places off its tours.

Elephants have long been the sentimental sweethearts of the circus. Chubby, wrinkly, and slow, they seem unthreatening and even comforting, more cuddly than wild. But we've learned that they are intelligent and sensitive, that they mourn their dead.

The mind of America has changed, Ringling realized, hearing Americans saying in so many words: Let these majestic creatures be.

The Elephants' New Home

I visited the Center for Elephant Conservation twice after the announcement. With a budget of $2.5 million, the center employs 22 people, about half of them full-time. Ringling estimates it spends $65,000 each year on the care of every elephant, including those on the road.

Ringling's public relations staff was polite and helpful but, no, they said, I could not spend a whole day wandering around and watching elephants. For my safety, they insisted that I ride in a golf cart with staff and a public relations person. I would see the activities of an elephant's daily life, but it would be staged just for me.

For my first visit, Ringling also brought out its CEO. Feld greets me with a quick handshake on a hot sunny afternoon outside a drab green metal manufactured home that houses the center's offices and the science lab, where frozen semen is stored.

Feld, whose company also owns Disney on Ice and other big extravaganzas, is the P. T. Barnum of our times, without the circus impresario's outsize personality. He is estimated to be worth $1.8 billion. He wears a nondescript sport shirt, black jeans with a wide black belt, and slip-on black shoes. He is slight of build, with receding close-trimmed hair, glasses that darken in the sun, and a crisp, clipped manner that comes across as aggrieved. Before we part I say, "You seem like an angry man." He replies, "I prefer the word 'passionate.' "

"Every time an animal rights organization came up against us in a court of law, they've lost," Feld tells me. "We're pitching a shutout. But I can't fight city hall," he says, referring to an ever changing patchwork of restrictions in about 65 municipalities in 32 states.

His decision also bows to customers. "We're in the entertainment business. It takes away from the total enjoyment when you're getting yelled at, and your kids are getting yelled at, by these activists. Then the five-year-old kid is hysterical, and the mother feels terrible."

His voice rises: "Why have an ounce of negativity? I want parents to feel like heroes for taking their kids to the circus."

Since June 1995, when this site opened, 21 elephants have been born here. Shirley, a 20-year-old elephant, became pregnant last fall by Charlie, a seasoned stud, and is due to calve in September 2016. Residents range from Mike, who's not quite two, to Mysore, who, named for an Indian city, is 69 years old.

Feld intends to keep breeding elephants, even though his circus won't need them anymore and, experts forecast, other circuses may soon retire them, too. Several North American zoos have already closed their elephant exhibits. The Detroit Zoo was the first, in 2005, sending Winky and Wanda to a 2,000-acre California sanctuary. Feld disdains that sanctuary and others.

"We do not call ourselves a sanctuary," he says. "Places that say they are sanctuaries manage to extinction. We manage for survival of the species."

Worlds Apart

The California sanctuary, run by the Performing Animal Welfare Society (PAWS), offers elephants rolling hills, lakes to bathe in, and trees to browse; there's enough room that females can wander all day and sleep where they choose.

In contrast, Ringling's spread is flat and treeless except for the bamboo and other vegetation planted in the past two decades and fed to the animals as roughage. Ringling's female elephants and youngsters sometimes graze in vast pastures, but may also be penned for the day on an acre of sand, as males always are. One male, Gunther, frequently balances himself on the five 80-pound rubber balls in his enclosure. Other pens have fallen trees, chunks of concrete, or an old tire as diversions.

They are missing the most important experience, which is freedom in the wild. It's like keeping a Ferrari in the garage.Ed Stewart, president, Performing Animal Welfare Society

The elephants have been trained from birth to sleep indoors and count on food after they're tethered with an ankle chain for the night. Staff says it's to keep them from stealing each other's meals.

PAWS president and co-founder, Ed Stewart, applauds Ringling's decision to retire its elephants and care for them. But he insists that bull hooks and shackling are unnecessary. Worst, says Stewart, is that Ringling continues to breed elephants that will spend every day of their lives in captivity. "They are missing the most important experience, which is freedom in the wild," he says. "It's like keeping a Ferrari in the garage."

Elephants retired from circuses or zoos are retrained at PAWS without bull hooks. Instead, bamboo sticks with tips softened by paper towel and masking tape are used. Ringling's staff does not hide the bull hook. The tool is carried by handlers whenever they are with the animals, for protection if one steps too close, or to guide the animal, for example, to lift its foot higher. The best behaved elephants, I was told, rarely need a prod. Activists allege they behave because they've been hurt by the tools in the past.

A staff member hands me one, joking, "This is the infamous instrument of torture." The tool is two feet long and weighty like a pipe. Its tip is stainless steel, with two stubby points. It has been compared with an ice pick, but neither point is sharp enough to puncture human skin, let alone elephant hide. Yet it could cause pain, I imagine, if used with force.

I tour the campus with Trudy Williams and her husband, Jim Williams, who helped design the center 20 years ago. Elephants brought the two together: He worked as a handler for her uncle, who keeps five elephants in Southern California, mostly for use by Hollywood. (The Asian elephant that appears in TV ads for the Spiriva inhaler is one of his.)

Jim, a strapping man with windblown blond hair, guesses he has known about 120 elephants, not just by sight but by personality. Jim and Trudy, who have occasionally worked on the road, say they have never seen an elephant treated abusively. They dismiss animal rights protestors as zealots. "It's a religion," says Trudy, a petite woman, with deep blue eyes and wavy auburn brown hair, who wears small sterling silver elephant earrings. "They're a business, with salaries to meet," counters Jim. "We both use animals."

The property is vast and well tended. I catch no aromas but that of a neighboring orange orchard in blossom. Barns are meticulously tidy, orange hoses looped against the walls, brooms clean and in place. Fans stand ready to spin away heat and mosquitoes.

I see the big barn, with 22-foot ceilings, where most females spend the night, fed once or twice, sleeping on their feet or, occasionally, lying down for an hour or two. Its concrete floors are swept free of food scraps and poop each morning, then hosed down.

And I see the pole barn where a semi drops off 21 tons of hay every two weeks. The elephants eat two bales (or 80 pounds) a day. The animals here and at the PAWS sanctuary are fed pretty much the same: hay, grains, produce. Favorites here are carrots, apples, and corn in the husk. Cheap bread, à la Wonder Bread, is a daily treat.

We spend quite a bit of time with females Alana and Icky, and I feed a carrot to Alana. "Hold it out, and she'll find it," Trudy tells me. So I do, and she does. Alana grasps the carrot in her trunk, as if it were a fist, and tosses it into her mouth. While our backs are turned, she snatches three at a time from Trudy's yellow bucket.

Trudy demonstrates the bath elephants get. Saying, "turn," and "foot," and "trunk," and "steady," she hoses down Icky's five-ton body and fills her mouth with water, which she downs with audible gulps. When Trudy turns away to spray Alana, Icky ambles to a pile of sand and, sucking it into her trunk, blows it all over her body, even onto her belly. It's as if she's a mound of bread dough, dusting herself with flour. The dirt, like mud if she could get it, protects her skin from sun and insects.

What happens on the road, when they long for dirt after every bath? Says Jim, "When their headdresses go on they know, 'Now is not the time for that.'"

Alana and Icky are the center's showpieces. They are easy to be with and don't mind when I rub my hands all over their skin, which feels like textured polyester carpeting. As I stand between them, I can imagine how handy a tool would be if they stepped my way too quickly.

Male elephants are difficult to manage. In the wild they often lead solitary lives. Here, each has his own barn and yard—at a cost of about a million bucks each, Jim says. Yards are fenced with six-inch steel pipes standing two feet apart (so handlers can quickly slip through to safety) and buried two feet deep in concrete.

One male, P.T., named after Barnum, keeps acting up as we sit 20 feet away in a golf cart. He thrusts his trunk between the bars of his pen, cocks his head back, opens his mouth wide and snorts, revealing a huge pulsing muscle of tongue. Then whoosh! We're sprayed with sand he has sucked up, coating us in his indignation.

Suddenly we're hearing from people saying, 'How can you do this? How can you take our beloved elephants away?' They didn't say anything before!Kenneth Feld, CEO, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey

We watch Piper, just two and a half, as she paces a 30-foot oval around a tire in her pen, trotting the path, having worn it down 12 inches. She doesn't pause to look at us.

In the distance stands Barack, born the day before President Obama's first inauguration in 2009. As historic as his election was, elephant Barack's birth was noteworthy too. He was the first elephant at the center conceived by artificial insemination. Every attempt since has failed. When he was born not breathing, Trudy and others did mouth-to-trunk resuscitation to save him.

Might we see him up close? No. "He's just coming into male maturity," says Jim. "Once they reach maturity they become unmanageable. Their testosterone spikes and boom!"

Imposing even at a distance is Vance, seven tons, his ears spread wide, his head high. Most males are too aggressive for the road, but Vance is valuable to Ringling.

According to a complex family tree on the office wall, Vance has fathered 24 offspring in his 48 years.

I'm also kept away from the baby of the bunch, Mike. I'm told he could swing his trunk around me and drag me against his fence. He might have gone on the road as a youngster, pre-testosterone. Now, instead, his life's work will be to breed more elephants.

Why?

First, Feld aims someday to show tourists the grandeur of the Asian elephant, if not at the center then someplace nearby, within an easy drive of Disney—although everyone insists, "We'll never be like Disney!"

Second, he's investing "every cent required" in research he calls "potentially the greatest thing ever in my life, and may be the greatest thing ever in everyone's life." Joshua Schiffman, a pediatric oncologist at the University of Utah, is using blood from Ringling elephants to study why elephants rarely develop cancer. He's searching for a genetic protector, hoping it might prevent cancer in humans.

Meanwhile, Feld is shrugging off demands from activists that he speed up the retirement of his performing elephants. "It's not like moving a bowl of goldfish," he says.

In some cities, circus attendance has improved since the announcement, I'm told. It's bittersweet for Feld. "Suddenly we're hearing from people saying, 'How can you do this? How can you take our beloved elephants away?' They didn't say anything before!"

He chuckles ruefully. "They may be the silent majority defeated by the vocal minority. How's it said? You don't know what you're going to miss till it's gone."

"But the good news is: The elephants aren't gone. They're here."

This story was updated on January 15, 2017 at 11:30am ET.