New Theory for What Caused Earth's Second-Largest Mass Extinction

Scientists have been trying to unravel what killed nearly all of Earth’s animals 400 million years ago. Could it be monstrous deformities caused by toxic metals in the ocean?

Toxic metals unleashed by depleted oxygen in the oceans may have helped trigger one of the largest extinctions of life in the planet’s history, new research suggests.

High levels of lead, arsenic, and iron—which continue to harm animals and humans today— appear to have caused deadly deformities in tiny, plankton-like creatures that teemed in Earth’s ancient seas.

The series of extinctions that occurred during the Ordovician and Silurian periods between 445 and 415 million years ago wiped out as much as 85 percent of all animal species on Earth. It was the second largest mass extinction in history, coming at a time when nearly all existing animals lived in the oceans.

Scientists previously suggested a number of possible scenarios to explain the massive die-off, including rapid cooling, volcanic gases poisoning the atmosphere or deadly gamma ray bursts from a hypernova. But evidence is lacking.

The new theory instead implicates changes in ocean chemistry. Metals that naturally lie on the ocean floor dissolve when seawater oxygen drops due to an influx of nutrients or other causes.

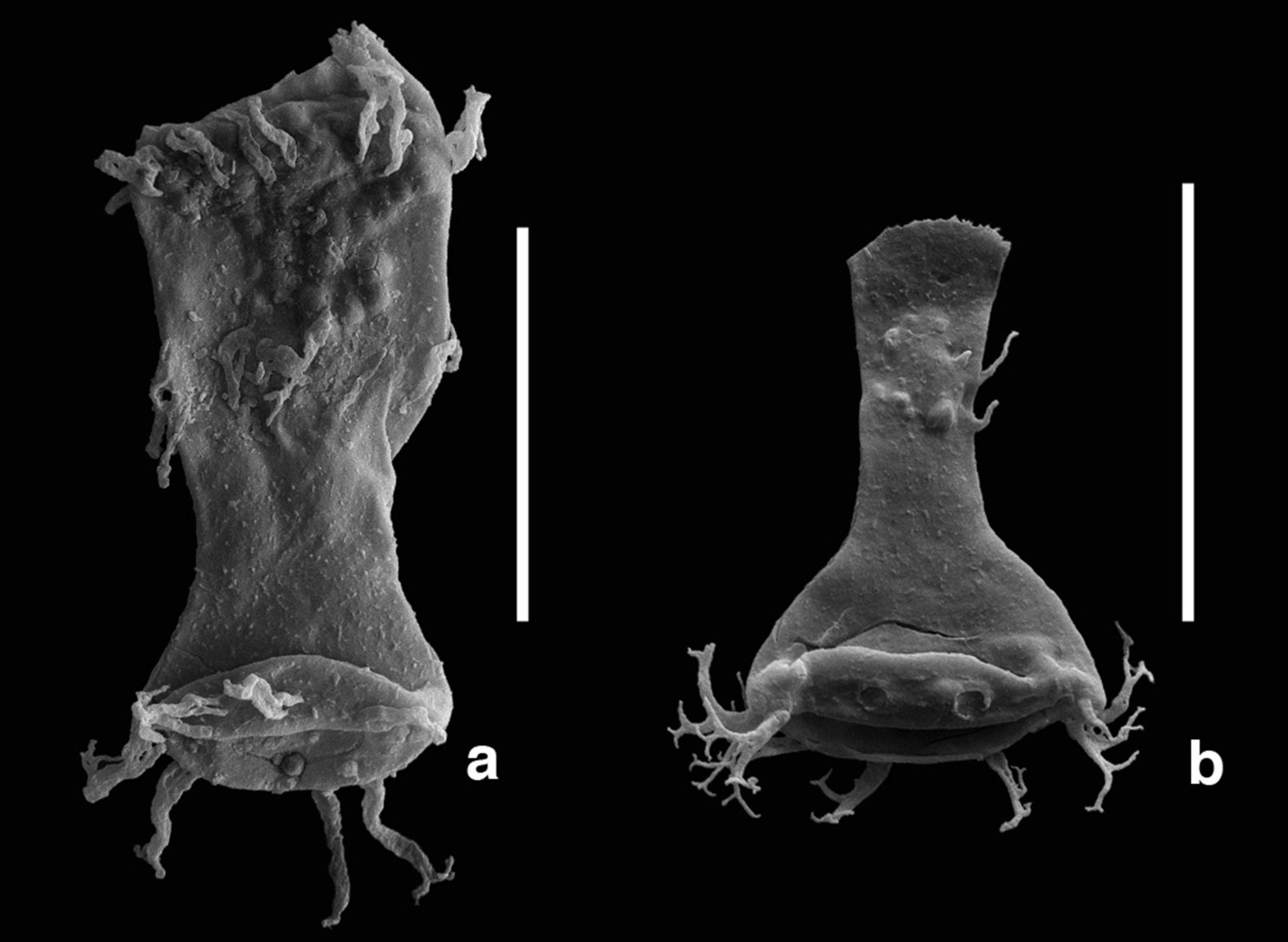

Rising exposures to the metals are believed to have caused the planktonic creatures to develop into “monstrosities,” according to the study published in Nature Communications.

“Imagine two, three, four individuals that have grown into each other (conjoined twins); monstrosities that have parts of specimens that are many times the size of those of regular specimens, or eggs in a string that are not fully separated,” Thijs Vandenbroucke, of France’s University of Lille and Belgium’s Ghent University wrote in an email.

Vandenbroucke is a paleontologist on an international research team that examined fossils from a 1.3-mile-deep bore in the Libyan desert.

The fossils displayed as many as 100 times more deformations than expected from background studies, along with up to 10 times greater heavy metal concentrations. The monstrosities were most pronounced in chitinozoans—miniscule, bottle-shaped eggs clad in a durable organic material that lasted millions of years.

The chemical processes that we describe are similar between the ancient and the modern ocean.Poul Emsbo, U.S. Geological Survey

Similar deformities are seen in marine and freshwater organisms today, a sign of exposure to high levels of toxic metals, says study co-author Poul Emsbo, a geochemist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Colorado.

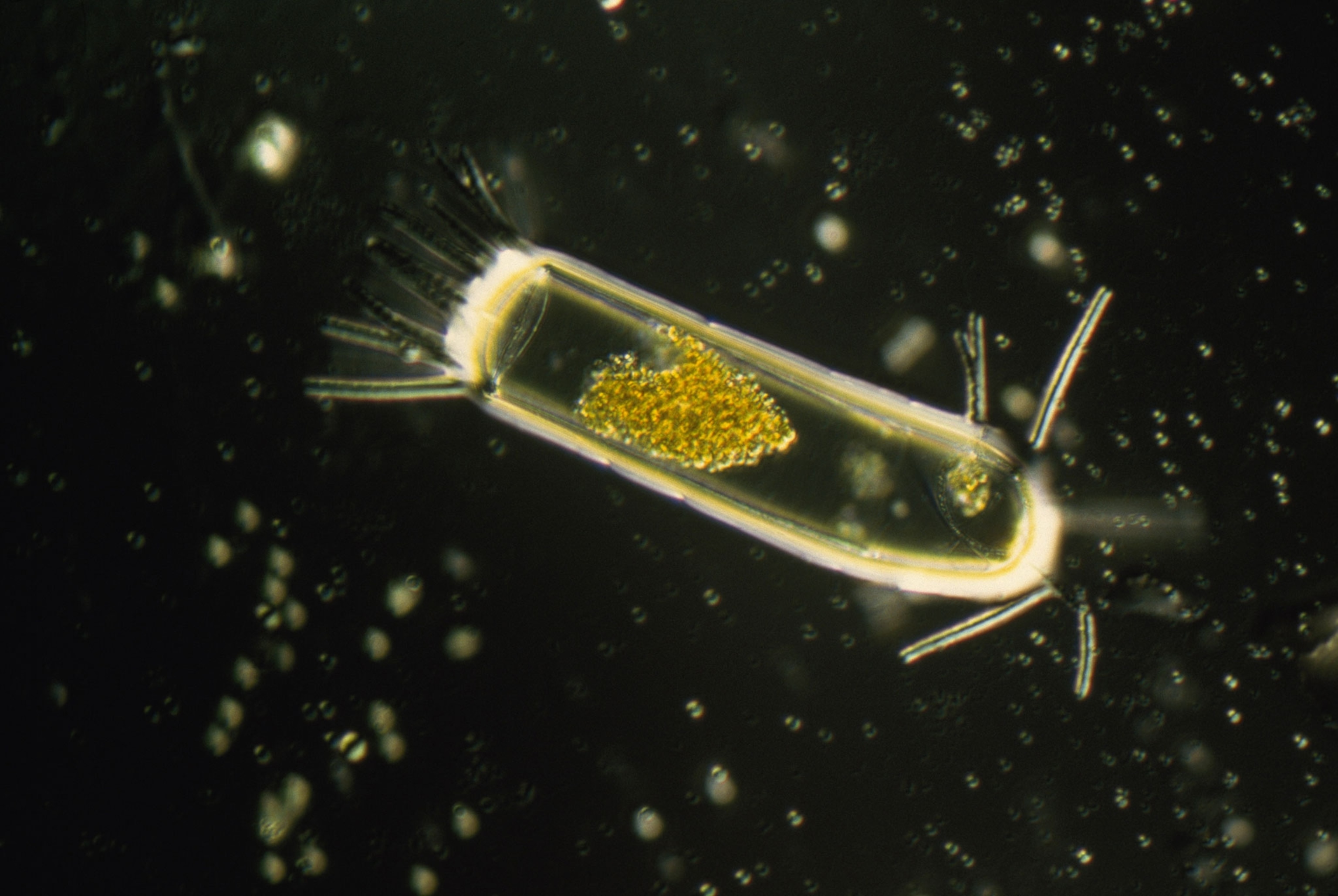

For example, in today’s diatoms, which are encased in a “perfect, delicate box,” Emsbo says, “the valves of the little box can be completely deformed, such as a zigzag pattern.” Those deformities are routinely used to detect metal pollution in waters, he said.

While changes in sunlight, pH or salinity levels can also trigger deformities in marine life, scientists have found little evidence that any of these occurred at the onset of the Ordovician-Silurian extinction. So the extremely high levels of toxic metals, the authors concluded, are the most likely explanation for this event, and may play a role in other ancient mass extinctions.

“It’s one of the more novel hypotheses for the Ordovician extinction that I’ve heard,” says University of California, Davis paleoclimatologist Howard Spero, who was not part of the study. “I’m never comfortable with ice sheets as triggers for mass extinctions,” he says, because ice ages may be too short. “And so the idea that the ocean chemistry was playing a significant role… that’s a very intriguing hypothesis.”

Heavy metals can disrupt the formation of seashells. And they also harm fish, birds, and other animals, including humans, says Myra Finkelstein, an environmental toxicologist at University of California, Santa Cruz. Lead is highly toxic across all vertebrate species. And arsenic can cause cancer.

While the scientists can't say exactly what caused the depleted oxygen in the ocean millions of years ago, leading theories center on increases in nutrients, such as nitrogen, that cause plants to grow faster and use up all the oxygen.

Today, expanding dead zones, such as a giant one at the mouth of the Mississippi River, are triggered by nitrogen-rich fertilizer and other runoff from cities and farms.

In addition, scientists say warming temperatures are sucking oxygen out of deep ocean waters, making enormous stretches of the seas hostile to marine life. [Read more about this phenomenon here.]

Although heavy metal loads could increase in these zones, it’s unlikely to occur on the scale seen during the major historical extinctions.

Still, “the chemical processes that we describe are similar between the ancient and the modern ocean,” Emsbo says. “So our study might indeed help highlight processes and hidden consequences caused by fluxes of anthropogenic elements to the world’s oceans.”