Through a Shark's Eyes: See How They Glow in the Deep

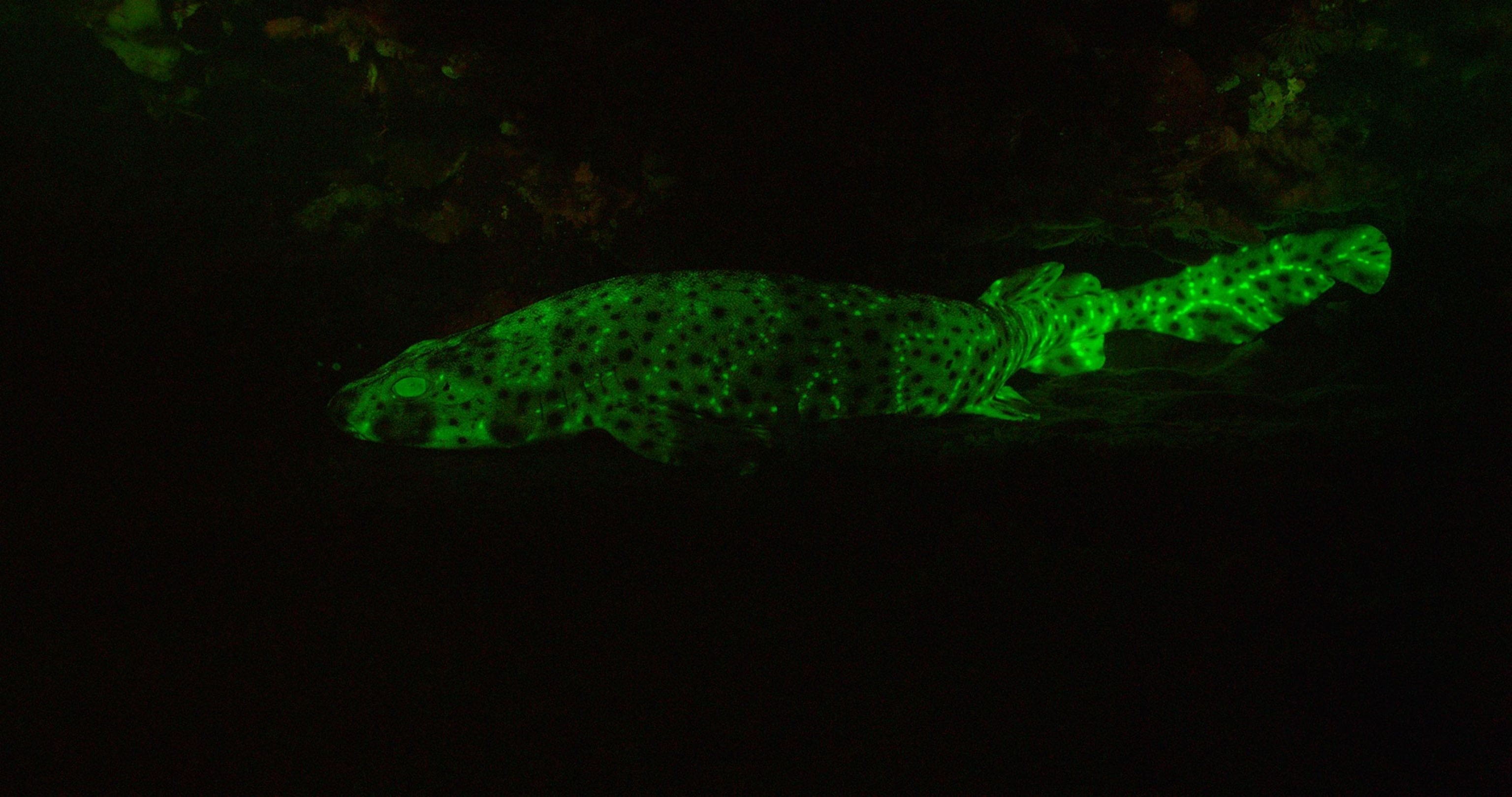

Scientists have built a camera that approximates how sharks see each other, revealing how they glow through biofluorescence.

For the first time, scientists have studied the eyes and skin of a group of shy sharks that live deep in the water, in a dark blue realm of low light. The team discovered that the secretive, little-known animals use biofluorescence, or glowing, to become more visible to each other, presumably so they can mate.

The team also found new evidence of the evolutionary history of biofluorescence in fishes, suggesting that the phenomenon is more widespread and more important than previously believed. In fact, biofluorescence in fishes was only discovered a few years ago, and scientists are only starting to figure out how it works. It is thought to be used in more than 200 species of sharks and bony fish, as well as marine turtles.

New research published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports described biofluorescence in two species of catsharks, the chain catshark (Scyliorhinus retifer) and the swell shark (Cephaloscyllium ventriosum).

These small sharks grow no more than three feet (one meter) long and spend much of their time on the bottom, to a depth around 1,600 to 2,000 feet (500 or 600 meters). They are shy and nocturnal and often hide in crevices.

"The cool thing about this research is it literally shines a light on animals that are often overlooked," says David Gruber, the study's lead author and a National Geographic Emerging Explorer, who is also a researcher at Baruch College, City University of New York and the American Museum of Natural History.

"These two species are often caught by fishermen as bycatch and we studied them not far from San Diego's best surfing beaches, but no one had looked at them," says Gruber. (See pictures of other animals that glow.)

How Sharks Glow

The catsharks generally live deep enough that they are bathed only in blue light, since the rest of the wavelengths of light are blocked by the water above. The sharks have a special, as-yet-unidentified pigment in their skin that absorbs blue light and re-emits it as the color green, in a process called biofluorescence. This is different from bioluminescence, where animals either produce their own light through a series of chemical reactions, or host other organisms that give off light.

To better understand how the biofluorescence works, Gruber and team examined the sharks' eyes. They found really long rods, which help the animals see in low light. They also found one visual pigment for color detection, which lets them see in the blue and green spectrum. Humans, in contrast, have three color pigments—red, green, and blue—allowing us to see a wider range of colors. At the high end, mantis shrimp have 12 pigments and can see an even wider array of colors.

Once the scientists worked out how the sharks likely see, they created a "shark-eye" camera to approximate the vision. They did this by adding filters in front of a lens of a Red Epic camera to restrict the wavelengths of light passing through, mimicking the shark's eye. To enhance the effect of fluorescence, they also sometimes shined blue lights. The team donned scuba gear and swam into Scripps Canyon, off San Diego, to find catsharks.

Under the natural, dim lighting, the sharks were hardly visible against the walls of the canyon to the human eye. But through the shark-eye camera, they appeared to glow a bright green, thanks to their biofluorescence. Their glowing patterns really "popped" against the background, thanks to the high contrast, Gruber notes.

"Imagine being at a disco party with only blue lighting, so everything looks blue," says Gruber. Some things will look lighter blue and others will look darker blue. "Suddenly, someone jumps onto the dance floor with an outfit covered in patterned fluorescent paint that converts blue light into green. They would stand out like a sore thumb. That's what these sharks are doing."

Battle of the Sexes

The two shark species showed distinct glowing patterns and differences between the sexes.

The swell shark is covered with small, bright green fluorescent spots over much of its body (those spots appear light beige under white light). But the females have a unique “face mask” of glowing spots and more dense ventral spotting that extends further back than males.

The chain catshark has an alternating light and dark fluorescent pattern but no spots. In females the reticulated pattern is even more pronounced. In males the pelvic claspers, used in mating, glow.

The sharks are thought to be primarily nocturnal and solitary, although not much is known about their behavior or lifecycles. Biofluorescence is likely to be important to their survival, Gruber says, but right now scientists can only guess at its function. The most likely explanation is so potential mates can find each other.

"But they might also be using biofluorescence to communicate in a way we haven't thought of," says Gruber. "It reminds me of when researchers first tuned in to the high frequency of bat sounds, and they discovered all this hidden chatter. They had to then figure out what it meant."

It's also unclear whether the animals' predators—larger sharks—or their prey—smaller fish and invertebrates—can see the glowing.

More Glowing Fishes?

Gruber's team took their work a step further to review everything that's been published on glowing fish. They found that the ability seems to have evolved at least three times among the sharks and rays, in the distantly related families Urotrygonidae (American round stingrays), Orectolobidae (wobbegongs), and Scyliorhinidae (catsharks).

That's significant because it further suggests biofluorescence plays an important role in the animals' lives, and it suggests there are different ways it is done. Further, more glowing organisms are also likely waiting to be discovered.

Gruber and team's work is "exciting and at the frontier of this science," says Victoria Elena Vasquez, a shark researcher at Cal State's Pacific Shark Research Center. "Their work delves into the next steps of biofluorescent research in marine species."

Previously, scientists had thought sharks mostly relied on smell, hearing, and the sensing of electrical signals to find their way around their environment, but this recent research suggests vision may be more important than experts previously realized. Vasquez adds that she is particularly intrigued by Gruber's finding that biofluorescence in the sharks appears to allow their contrasting coloration to be more discernible at greater depths. The fact that this might help the sharks find mates seems plausible, she says, although more research is needed.

"This work forces us to take a step out of the human perspective and start imagining the world through a shark's perspective," says Gruber. "Hopefully it will also inspire us to protect them better," he says, noting that an estimated 100 million sharks are killed by people each year.