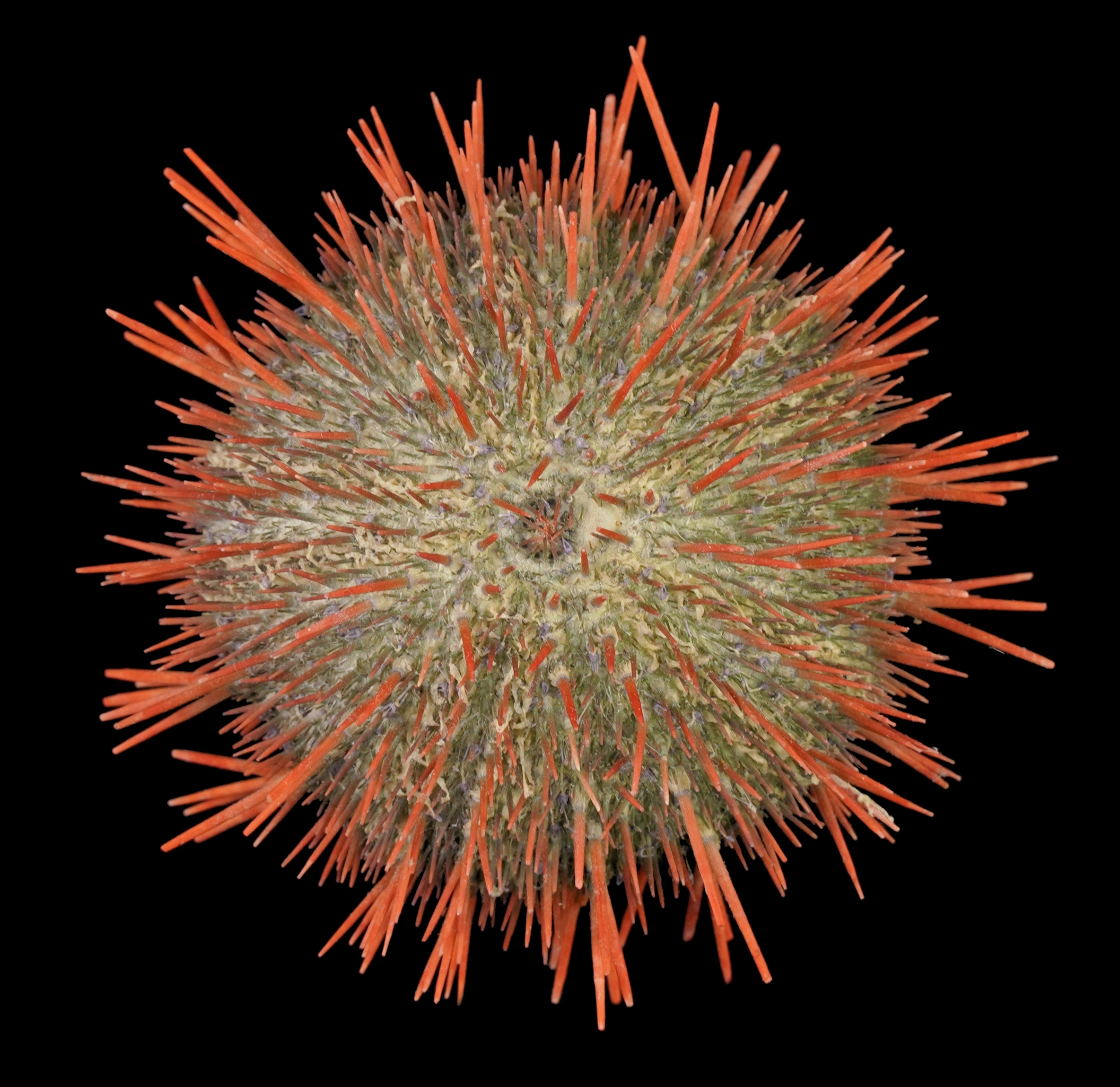

Beneath sea urchins’ exterior spines, rounded skeletons called tests are jewels of color, texture, and symmetry. There are hundreds of urchin species, and they’re found in every ocean on Earth, from the intertidal zone to more than four miles below the surface. In 2018, Anders Hallan, a research associate at the Australian Museum in Sydney, began photographing urchin skeletons that had washed up on beaches or been collected by divers and those on fishing or research vessels. He created a composite image over the course of a week in 2024 using 76 individual photographs.

(Sea Urchin Genome Reveals Striking Similarities to Humans)

The project comes at a perilous moment for these creatures. Since 2022, sea urchins have been plagued by a scuticociliate, a single-celled pathogen that eats away at the animals’ soft tissue and makes their spines fall off. A mass die-off that started in the Caribbean that year has since spread east, likely through the Mediterranean, into the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. In some survey locations, researchers found thousands of dead urchins.

The animals’ survival is vital to the health of reefs, where they eat algae that can smother coral. It’s one of the many reasons Hallan is committed to capturing their beauty: “They are really quite ingeniously evolved.”

Hallan often photographs sea urchins from above to reveal their radial symmetry. On the animal’s opposite side, its mouth contains five self-sharpening teeth for chewing foods like algae, kelp, and plankton, and for carving nooks into rocks where it can hide from predators.

The word “urchin” derives from a 14th-century word for “hedgehog.” Like their terrestrial namesakes, sea urchins are known for their spines, which are flexible and strong and serve multiple functions, from defense against predators to locomotion and sensing. Usually the spines detach from the test when an animal dies, but some of these urchins were specially preserved to keep their spines intact.