U.S. Faces Growing Feral Cat Problem

The offspring of stray household pets, feral cat numbers are on the rise.

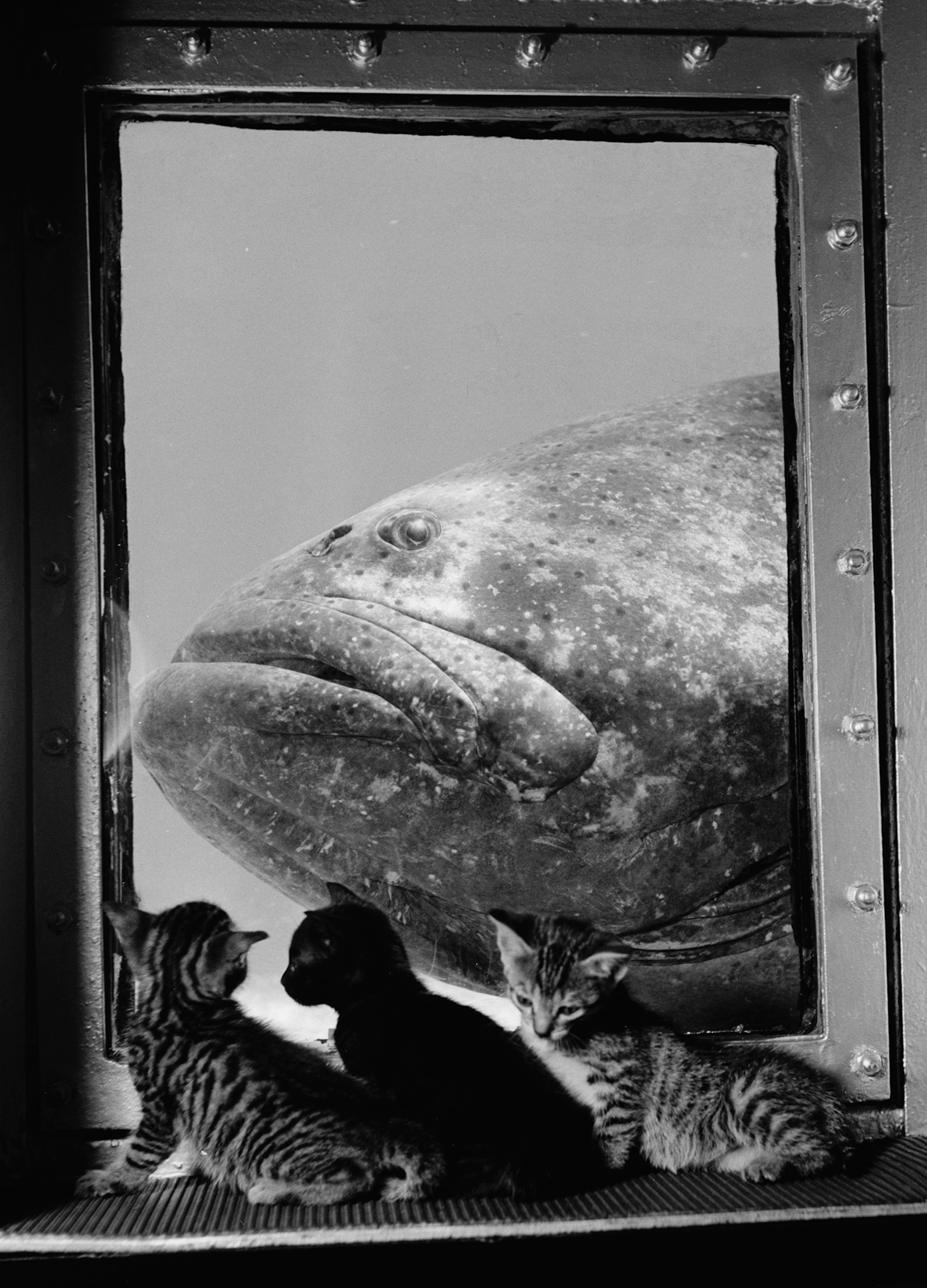

You may have seen them wandering through parks or languishing behind restaurants. At first, these cats look domesticated. But they're really wild animals.

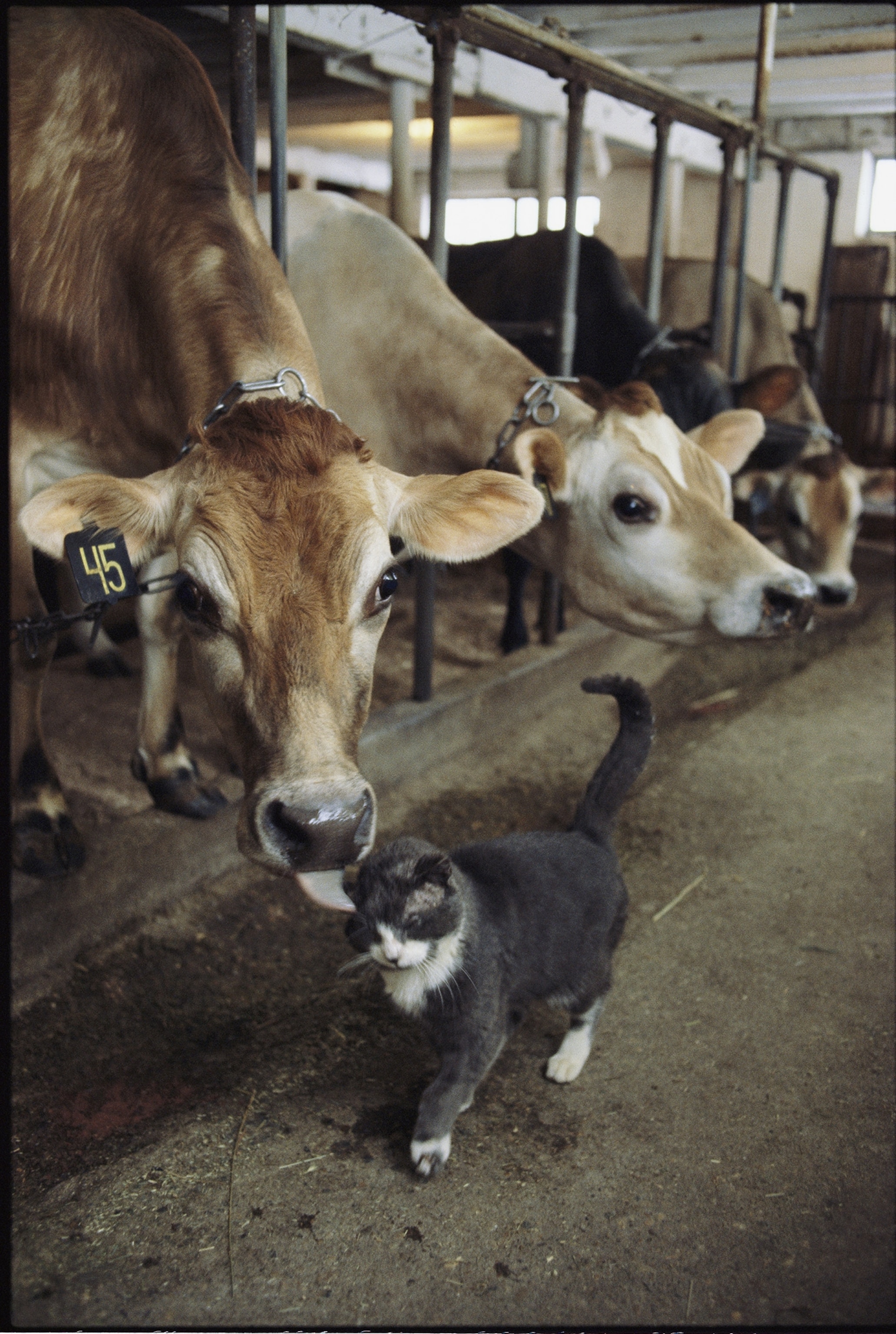

Feral cats are the offspring of stray or abandoned household pets. Raised without human contact, they quickly revert to a wild state and form colonies wherever food and shelter are available.

Many city and county animal control agencies are mandated only to deal with dogs—not cats. So for decades feral cats have remained untouchable.

Some feline experts now estimate 70 million feral cats live in the United States, the consequence of little effort to control the population and of the cat's ability to reproduce quickly.

The number concerns wildlife and ornithology organizations that believe these stealthy predators decimate bird populations and threaten public health. The organizations want the cats removed from the environment and taken to animal shelters, where they are often killed.

That's caused a chorus of hisses from feral cat advocates who say the cats are unjustly being blamed for killing wildlife. Thousands of volunteers and animal welfare groups throughout the country stepped forward in the early 1990s to control the wild cat population through mass sterilization programs.

Ron Jurek, a wildlife biologist for the California Department of Fish and Game, has kept a close eye on the impact feral and free-roaming domestic cats have on native species, like the California least tern, a federal endangered bird that nests along the coast.

"Cats do kill wildlife to a significant degree, which is not a popular notion with a lot of people," he said.

In urban areas, he said, there are hundreds of cats per square mile (1.6 square kilometers)—more cats than nature can support.

Exact numbers are unknown, but some experts estimate that each year domestic and feral cats kill hundreds of millions of birds, and more than a billion small mammals, such as rabbits, squirrels, and chipmunks.

Feline predators are believed to prey on common species, such as cardinals, blue jays, and house wrens, as well as rare and endangered species, such as piping plovers and Florida scrub jays.

For more than ten years, Jurek says, feral and domestic cats have been a persistent problem in California, killing one or two colonies of least terns each year. The small white birds are part of an intense monitoring program with a tremendous number of volunteers who watch the colonies throughout the six-month nesting season.

"If a cat finds the colony, it can destroy the colony in a few days, if not overnight," Jurek said.

Bird Decline "Caused by Humans"

Michael Mountain, one of the founders of Best Friends Animal Society in Kanab, Utah, says there is no evidence that feral cats are to blame for a decline in the bird population at large.

"Ferals are savvy, don't have enough to eat, and have to live like real (wild) animals," Mountain said. "So the last thing a feral cat wants to do is waste his energy chasing after birds."

Instead, he said their diet consists of mice, insects, and lizards.

Mountain said his views on this issue are not one-sided. The 3,300-acre (1,300-hectare) Best Friends animal shelter, which is the largest in the country, not only cares for feral and domestic cats—it also cares for birds.

The decline in songbird populations is caused by many factors, Mountain says, including habitat loss, pollution, pesticides, and window strikes.

He also notes a new report by David I. King of the U.S. Forest Service's Northeastern Research Station and John H. Rappole of the Smithsonian Conservation and Research Center. The study concludes that the biggest problem is the loss of the birds' winter habitat in the tropics due to deforestation.

"What we all need to do, since we all care about animals, is find real solutions (to controlling the feral cat population)," Mountain said. "Trying to kill off all the feral cats is not going to help the birds."

Linda Winter disagrees.

Winter is the director of the American Bird Conservancy's (ABC) Cats Indoors! campaign. The conservation group, based in Washington, D.C., started the program seven years ago to educate the public that free-roaming cats pose a significant risk to birds and other wildlife.

The conservancy believes feral felines should be removed permanently from the environment and taken to shelters. The majority of wild cats, though, cannot be domesticated. Consequently shelters kill them, sometimes minutes after the cats are dropped off.

"If people object to those cats being euthanized, since quite often homes can't be found for them, then those people should take those cats and put them on their own property or in stray and feral cat sanctuaries, where they can be protected and safe and not harm any other animal or harm the general public," Winter said. "That, to us, is the real solution."

Placing all the cats in sanctuaries is "totally impractical and completely absurd," counters Mountain. Best Friends is one of the few shelters in the country that houses feral cats—but only sick or disabled cats in need of special care.

"The likelihood of that being able to happen for millions of feral cats is, frankly, just silly," Mountain said. "And they [ABC] don't actually mean that at all. What they mean is to put something out [to the public] that sounds lovely—and which, of course, nobody can do—to justify the other approach, which is to kill them all."

Spay and Neuter

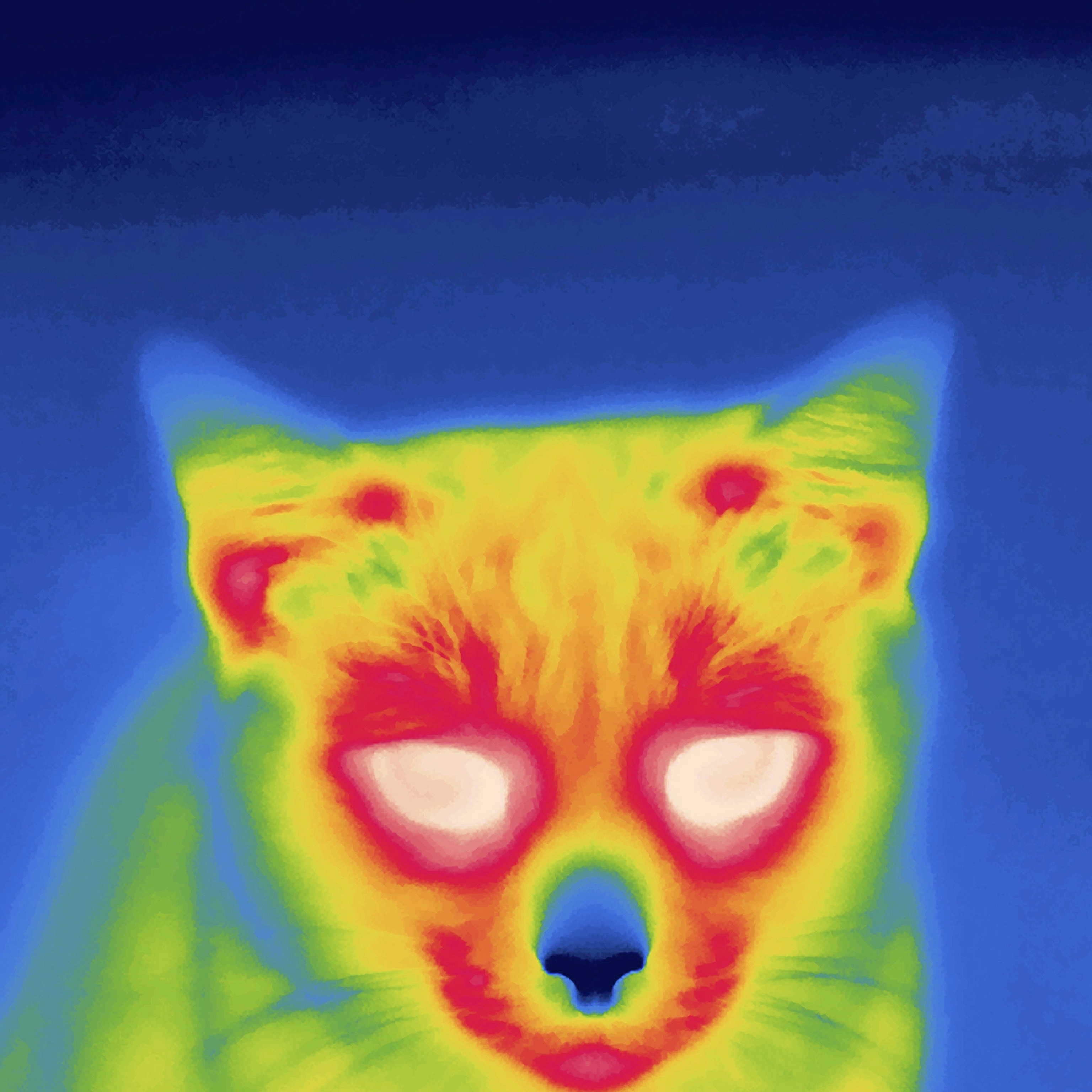

Julie Levy is a veterinarian and professor at the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine in Gainesville. She says the answer to permanently reducing wild cat populations is through the Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) method, in which entire colonies of cats are trapped, vaccinated, and sterilized by a veterinarian.

Homes are found for young kittens, which can be tamed. Healthy adults are returned outdoors, where volunteers feed and look after them for the remainder of their lives.

The method, though, is neither quick nor simple.

In a study conducted by Levy over an 11-year period, she found the cats lived an average of 7 years after being spayed and brought back to their territory.

"It's become a double-edged sword, because we're happy for the cats that they're living life and in good health," Levy said. "But it also means that we can't expect our neuter programs to work really quickly."

Levy is also the founder of Operation Catnip, the largest TNR program in the country. Monthly spay-neuter clinics are held where a team of 7 veterinarians and staff of 30 volunteers sterilize up to 150 cats within a few hours.

Many programs, like Operation Catnip, are backed by large-scale public and financial support.

In 1999, for example, the California Veterinary Medical Association's Feral Cat Altering Program was awarded a three-year, U.S. 9.5-million-dollar grant by a private foundation. The program fixed feral cats throughout the state for free, performing 170,334 surgeries.

Levy says something realistic needs to be done to reduce the feral population—but killing the cats, as many wildlife organizations have suggested, is not feasible.

"The people who feed these cats are not going to cooperate with those kinds of programs, and you have to engage the people who know where the cats are in any solution," she said. "So you can either harness this huge volunteer force to help in the solution or you can go to war with it."

The ABC's Winter, who is vocal in the battle between wildlife groups and feral advocates, says she opposes the TNR method because the released cats continue to kill wildlife. Another problem, she said, is that feeding stations maintained by caregivers attract animals like raccoons and skunks that carry rabies and other diseases, creating a public health threat.

The cats can also transmit diseases. In August, animal control officials in Eugene, Oregon, reportedly discovered more than three dozen feral cats infected with salmonella, which is contagious to people and pets. No humans, however, were reported to be infected.

"TNR is just not a solution that helps everybody and all animals involved," said Winter, an owner of two indoor-only cats. "They need to figure out another way."

Levy hasn't come up with another way. But she is currently working with a wildlife research group to develop a sterilization vaccine for female and male cats.

"We're on the trail of a good one," she said. "We're now one year into a two-year study with male cats, and it's looking extremely promising."

If the vaccine is developed, she said, trained technicians would go into the field and inject the cats. The vaccine would make TNR programs more efficient by helping reduce costs and labor.