These unearthly whale songs helped save humpbacks from extinction

Once at risk of being wiped out, humpback whales charted a remarkable comeback thanks to their songs. In 1979, National Geographic issued a record-breaking album of those tunes alongside a story about Roger Payne's groundbreaking research. In honor of Project CETI's current work decoding the speech of sperm whales, we're putting the original feature attached to the songs back online.

At dusk I sat in the stern sheets of our small sailboat, braced against a stanchion and using the last light of day to take a final sight on Bermuda's Gibbs Hill Lighthouse, 35 miles to the northeast.

We were too far from land to return that evening; my wife, Katy, and I would have to spend the night at sea. Bermuda's treacherous reefs are difficult enough to navigate in broad daylight. In darkness they are impossible.

As night deepened, a familiar feeling came over me, one of loneliness at sea. I felt at one with the other solitary watchers elsewhere on earth—the shepherds, sentinels, and herdsmen who huddled alone beneath these same stars, feeling the night close in around them.

To break the mood, Katy and I got down to work. We brought the boat about onto the other tack and pointed her as high into the wind as we could, so that she nodded gently with the waves. After lowering a pair of hydrophones into the sea, I switched on their amplifiers and listened in stereo through the headphones.

We were no longer alone! Instead, we were surrounded by a vast and joyous chorus of sounds that poured up out of the sea and overflowed its rim. The spaces and vaults of the ocean, like a festive palace hall, reverberated and thundered with the cries of whales—sounds that boomed, echoed, swelled, and vanished as they wove together like strands in some vast and tangled web of glorious sound.

I felt instantly at ease, all sense of desolation brushed aside by the sheer ebullience of it all. All that night we were borne along by those lovely, dancing, yodeling cries, sailing on a sea of unearthly music.

Often during that night off Bermuda I thought how the oceans had once heard these wild cries. How, once, the echo chamber of the sea had reverberated to the haunting "songs" of whales. Then I thought of what it is like today in many of the whales' former haunts—silent, lifeless, impressing one most with a sense of what has been lost.

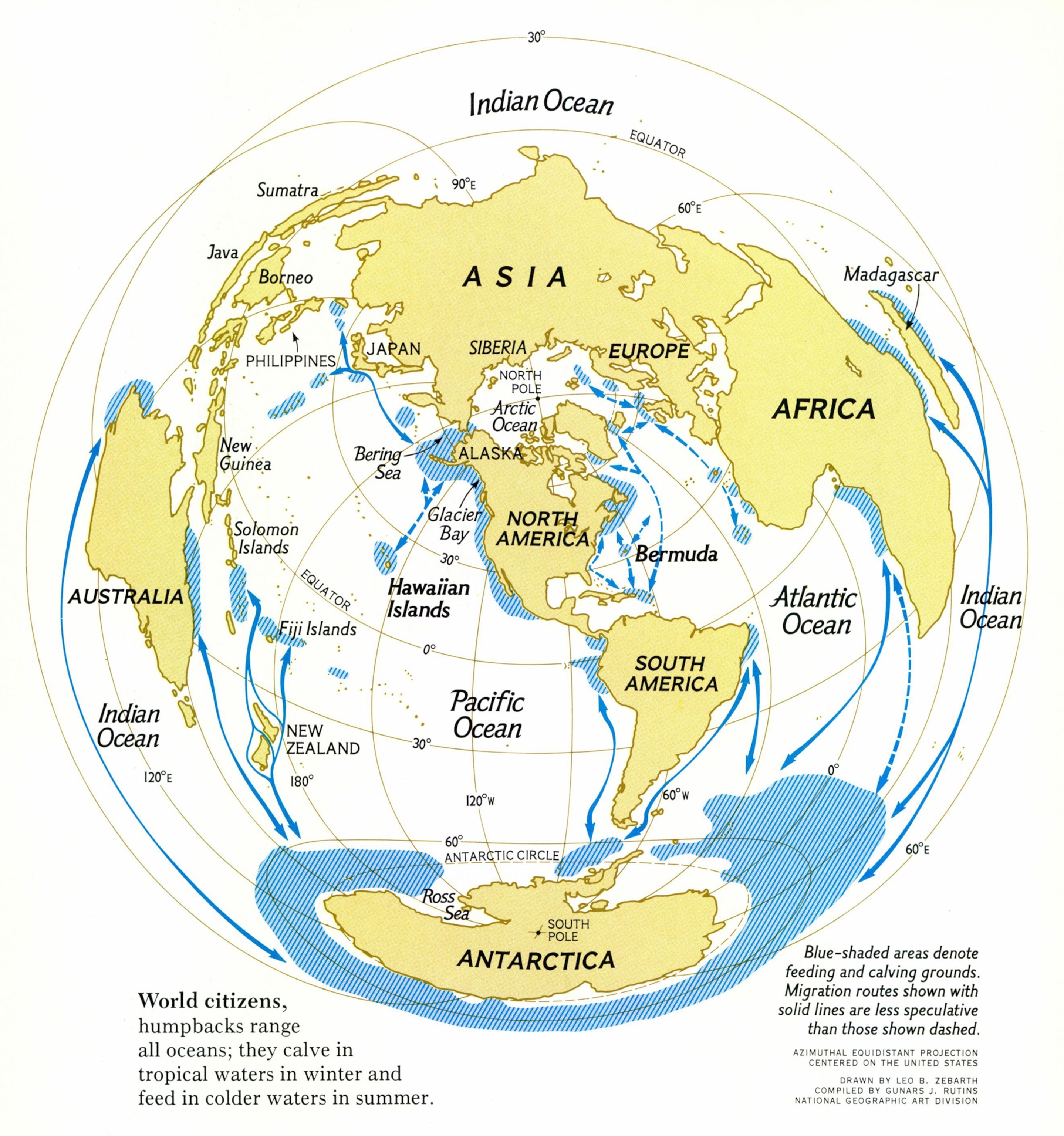

Humpback whales pass Bermuda each spring on their way north from southern calving grounds near Puerto Rico. During this period the humpbacks fill the ocean with complex and beautiful sounds. Many hours of these sounds were recorded and later analyzed with the help of a friend, Scott McVay, at Princeton University. The analysis showed that humpback sounds are in fact long songs. I use the term song not in a sense of beauty, although humpback sounds are indeed beautiful. By song I mean a regular sequence of repeated sounds such as the calls made by birds, frogs, and crickets.

Humpbacks change their tune

Most birdsongs are high pitched and last only a few seconds, while humpback songs vary widely in pitch and last between six and thirty minutes. Yet if you record a whale song and then speed it up about 14 times the normal rate, it sounds amazingly like the song of a bird.

When you go out to listen to a humpback sing, you may hear a whale soloist, or you may hear seeming duets, trios, or even choruses of dozens of interweaving voices. Each of those whales is singing the same song, yet none is actually in unison with the others—each is marching to its own drummer, so to speak.

The fact that whales in Bermuda waters are singing the same song at any given moment is not surprising when you think of how similar two robins or two cardinals sound. But if you collect humpback songs for many years and compare each yearly recording with the songs of earlier years, something astonishing comes to light that sets these whales apart from all other animals: Humpback whales are constantly changing their songs.

In other words, the whales don't just sing mechanically; rather, they compose as they go along, incorporating new elements into their old songs. We are aware of no other animal besides man in which this strange and complicated behavior occurs, and we have no idea of the reason behind it. If you listen to songs from two different years you will be astonished to hear how different they are. For example the songs we taped in 1964 and 1969 are as different as Beethoven from the Beatles.

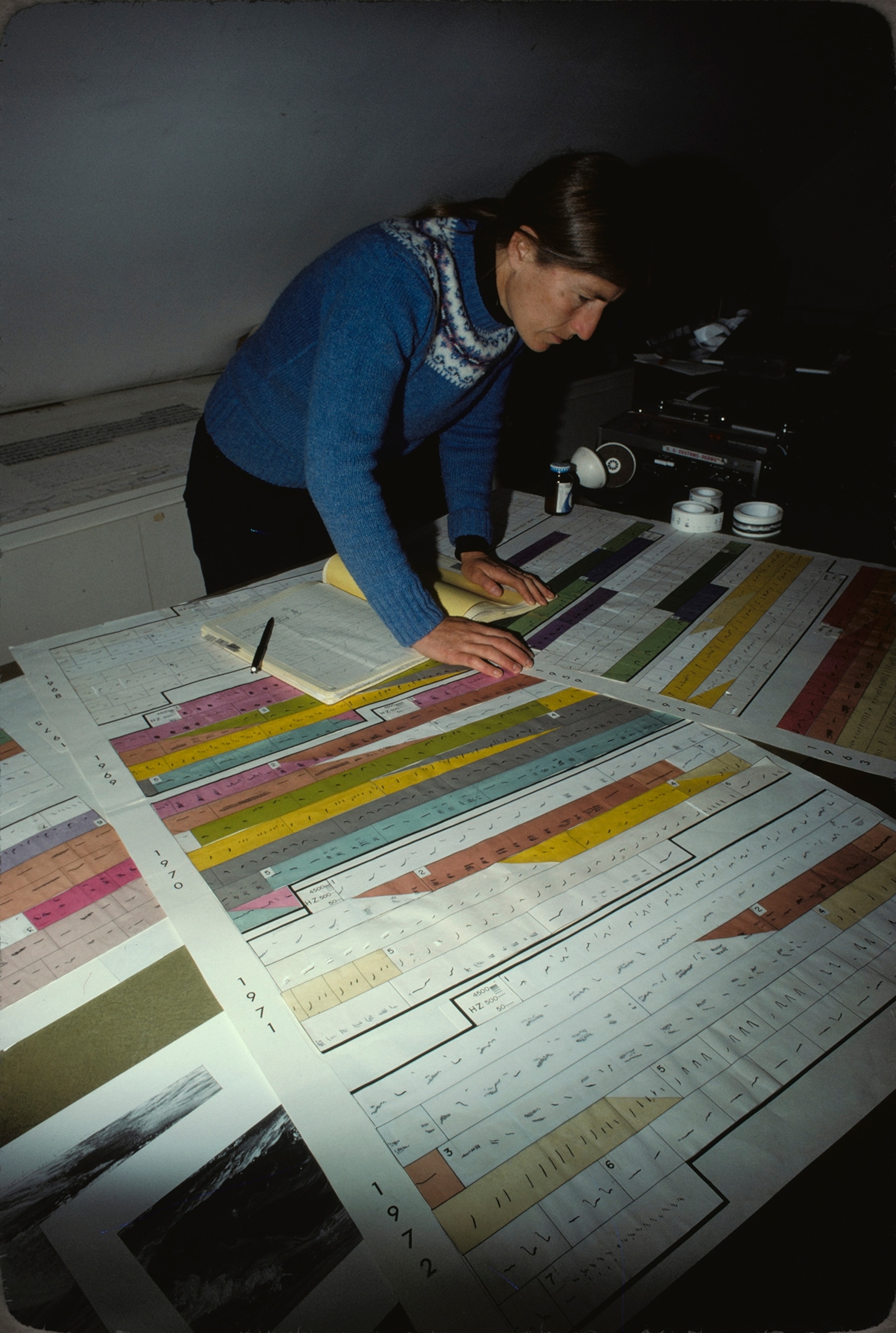

By combining our own tapes with those of friends like Bermudian Frank Watlington, we now have a sample spanning twenty years in Bermuda.

Katy and I have analyzed this data in detail. We find that the song has been constantly changing with time. All the whales are singing the same song one year, but the next year they will all be singing a new song. The yearly differences are not random, however. The songs of two consecutive years are more alike than two that are separated by several years. Thus, the song appears to be evolving, but regardless of how complex the changes are, each whale apparently keeps pace with the others, so that every year the new song is the only one that a listener hears.

Musical talent may be inherited

We have also recorded and analyzed four years of humpback songs from Hawaii, a major wintering area for humpbacks. Although songs of the same year in Hawaii and Bermuda are different, it is intriguing that they obey the same laws of change, and have the same structure. Each song, for example, is composed of about six themes-passages with several identical or slowly changing phrases in them. Each phrase contains from two to five sounds. In any one song the themes always follow the same order, though one or more themes may be absent. The remaining ones are always given in predictable sequence.

The whale populations of Hawaii and Bermuda are almost certainly not in contact. Thus, the fact that the laws for composing the songs are the same in both places strongly suggests that the whales inherit a set of laws and then improvise within them. Whether these laws are transmitted from one generation to the next genetically or by learning remains to be seen. When Katy first discovered that the songs of humpbacks were changing from year to year, a simple explanation seemed likely: Since the whales do not sing at their summer feeding grounds, and since the song is complex, perhaps the humpbacks simply forget the song between seasons and improvise a new version from whatever fragments they can recall.

To test this theory, we organized a season long study of humpbacks off the island of Maui in Hawaii.

The study had two objectives: to record a full season of songs and to make observations of the whales' behavior.

We were joined in the study by Al Giddings and Sylvia Earle, two of the most experienced divers in the world. Al, with his unsurpassed ability as an underwater photographer, and Sylvia, with her background in both diving and science, were ideal partners, as were our two graduate students, Jim Darling and Peter Tyack.

Songsters pick up where they left off

To me, the results of the study are fascinating. Over a six-month period we obtained samples of songs, coupled with unique observations of underwater behavior. The subsequent analysis of our tapes has revealed an intriguing fact: The whales had not forgotten the previous season's song, for they were singing it when they first returned to Maui. Only as the season progressed did the changes gradually take place. Obviously, during the period between breeding seasons the song is kept in "cold storage," without change.

Another fascinating thing we discovered is that the whales always sing new phrases faster than the old ones. We discovered, too, that new phrases are sometimes created by joining the beginning and end of consecutive phrases and omitting the middle part—just as we humans shorten "do not" to "don't." In many other ways the introduction of new material and the phasing out of old are similar to evolving language in humans.

So far, the study of humpback whale songs has provided our best insight into the mental capabilities of whales. Humpbacks are clearly intelligent enough to memorize all the complicated sounds in their songs. They also memorize the order of those sounds, as well as the new modifications they hear going on around them. Moreover, they can store this information for at least six months as a basis for further improvisations. To me, this suggests an impressive mental ability and a possible route in the future to assess the intelligence of whales.

Songs are not the only vocalizations of humpbacks; we often hear grunts, roars, bellows, creaks, and whines. These sounds sometimes accompany particular types of behavior, suggesting that they may have specific social meaning.

One such association between sound and behavior has been documented by Charles Jurasz, an independent researcher in Glacier Bay, Alaska. Chuck's 12-year study has added significantly to our knowledge of whales. On a recent visit with Chuck I recorded the underwater sounds of a hump back in the act of "spinning its net." Such sounds consist solely of expelled air. There are no accompanying social or vocal noises, which suggests to me that bubble netting is a deliberate act—that of a whale setting a trap.

Are we killing whales with kindness?

Only a few years ago the chief threat to humpback whales was the men who hounded them dangerously close to extinction. Today international agreement forbids the killing of humpbacks, but in some areas man threatens to love them to death.

In Hawaii increasing numbers of well meaning tourists now converge on the breeding grounds in small boats to observe and photograph the great creatures at close range. Observation can sometimes edge over into harassment, which is illegal under both the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act.

In 1976 I tackled the problem with Nixon Griffis, a longtime friend of humpbacks. Together we called on Elmer Cravalho, mayor of Maui County, who appointed Jim Luckey, manager of Maui's Lahaina Restoration Foundation, to be chairman of a citizens' committee to explore the problem. The result is an official organization to educate the public and so prevent harassment of the whales. Thus the citizens of Maui have taken a major initiative in generating local government and citizen concern for protecting a marine mammal on the endangered species list.

Plans are now under way to establish a Pacific Marine Research Center at Lahaina with support not only from Hawaiians but also from worldwide subscription.

Happily for whales, such efforts are on the increase. One recent development may have spread the songs of humpbacks not just from the oceans to the land, but throughout the galaxy. In late summer of 1977, Voyagers 1 and 2—spacecraft launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, toward other worlds in our galaxy—carried aboard unique recordings that included the works of Bach, Mozart, and a rock group, as well as a section entitled "The Sounds of Earth."

In the latter section delegates from 60 member countries of the United Nations offered a greeting in 55 languages. The messages were followed by a somewhat longer "greeting" from a humpback whale, recorded by Katy and me off Bermuda in 1970. In some ways this constitutes a step beyond all my dreams, in seeing whales become a symbol for the hope that there is still intelligent life on earth.

The expected lifetime of the records is a billion years. Should they be encountered by some other space-faring civilization, they would bear a message that had lasted longer than perhaps any other human work.

Could it be that mankind is simply the humpbacks' guarantee that its songs will be heard throughout the galaxy?

Click here to learn more about CETI’s groundbreaking new research to decode whale speech.