Why Man-Eating Lions Prey on People—New Evidence

An analysis of the notorious Tsavo man-eating lions' teeth has revealed some surprises.

"I have a very vivid recollection of one particular night when the brutes seized a man from the railway station and brought him close to my camp to devour. I could plainly hear them crunching the bones, and the sound of their dreadful purring filled the air and rang in my ears for days afterwards.” —Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson, The Man-Eaters of Tsavo: And Other East African Adventures

These chilling words recount how African lions terrorized a railroad-construction project in Tsavo, Kenya, more than a century ago, killing and eating 35 workers. But how and why the big cats became “man-eaters” is still a matter of scientific debate.

(How many people did the man-eating lions of Tsavo actually eat?)

For instance, some experts have suggested a lack of prey, brought about by a drought and disease epidemic in the late 1800s, forced the lions to feed on people out of desperation. But there's a problem with that theory—starving lions would have likely made the most out of every meal, eating the humans bones and all.

And despite Patterson's memory of bone crunching, a new analysis of the lions' teeth shows no signs that the animals devoured human bones.

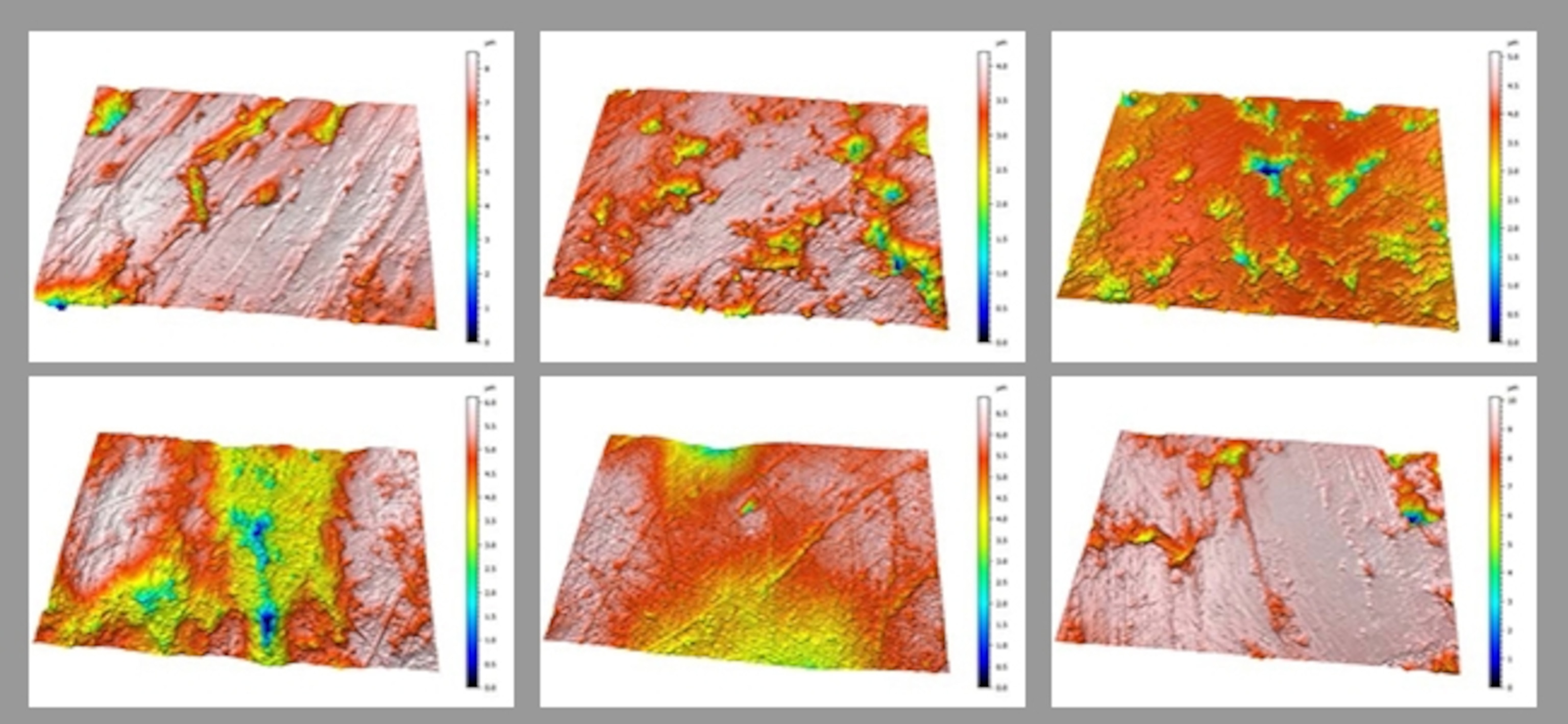

Study leader Larisa DeSantis, a paleoecologist at Vanderbilt University, and colleagues used 3-D imaging technology to map the microwear of the Tsavo lion teeth, preserved in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago after Patterson and other hunters finally shot the lions. The team also investigated the teeth of another lion that attacked at least six people in Zambia in 1991. (Read about living with lions in National Geographic magazine.)

Dental microphotographs of all three animals did not display the telltale peaks and valleys found in regular bone-crushing predators, such as hyenas, according to the study, published April 19 in the journal Scientific Reports. Instead, their teeth were smooth, similar to the wear patterns seen in zoo lions that eat soft foods such as beef.

This means the lions weren't attacking railroad workers as an act of last resort, but were likely supplementing people with other diverse foods.

“We often see ourselves as the top of the food chain, where in reality we have been on the menu of lions and large cats in general for a long time," DeSantis says. (See: "When Humans Are Hunted.")

Tooth Troubles

There's another layer to the mystery: Dental disease.

One of the Tsavo lions suffered from a broken canine and an abscess that likely caused the loss of several more teeth surrounding it, notes Peter Emily, founder of the Peter Emily Veterinary Dental Foundation. Similarly, the Zambia lion from 1991 had a fractured jaw that was so bad, the skin was broken and the wound would have been draining constantly.

Lions rely heavily on their teeth to grab prey, suffocating the animal or collapsing its trachea. Because of this constant use, about 40 percent of African lions have dental injuries, according to a 2003 study led by DeSantis's co-author, Bruce Patterson. (See "15 Intimate Portraits of Lions.")

Both the Tsavo and Zambia lions would have had trouble opening their mouths, so taking down a zebra or buffalo would have been excruciating, if not impossible.

As for the second Tsavo lion’s dental injuries, Emily says they weren’t too serious, which leads him to agree with DeSantis’s conclusion that the animal likely learned to attack people from the other lion.

Taking these mouth maladies into account, Emily adds, preying on humans makes total sense.

“We don’t have any fur or heavy hide, and our flesh would be very easy to eat.”

Adapt or Die

While earlier studies have failed to find a connection between dental disease and man-eating, there’s plenty of evidence that injured animals can adapt.

Anne Hilborn, a biologist at Virginia Tech, says she’s seen injured cheetahs switch to smaller, slower prey items like gazelle fawns and hares, rather than the adult gazelles, impalas, and even wildebeests they typically hunt.

But she doubts this strategy would work for lions. (Learn more about the National Geographic Society's work to save big cats.)

“The occasional baby gazelle might keep a cheetah alive, but I think a lion would struggle,” says Hilborn.

In the end, DeSantis says it’s unlikely any one factor—more humans, fewer prey, or bad teeth—led the lions down the road toward man-eating, but rather a combination of many stressors.

“One hundred years ago, the technology needed to answer this question wasn’t available, and a hundred years from now there will probably be new technologies we can apply,” says DeSantis.

“It really underscores the importance of museums for helping preserve fossils.”