Stunning new sea slug species look just like seaweed

"This may be the best example of an animal masquerading as a plant that we have," one researcher said of the camouflaged creatures.

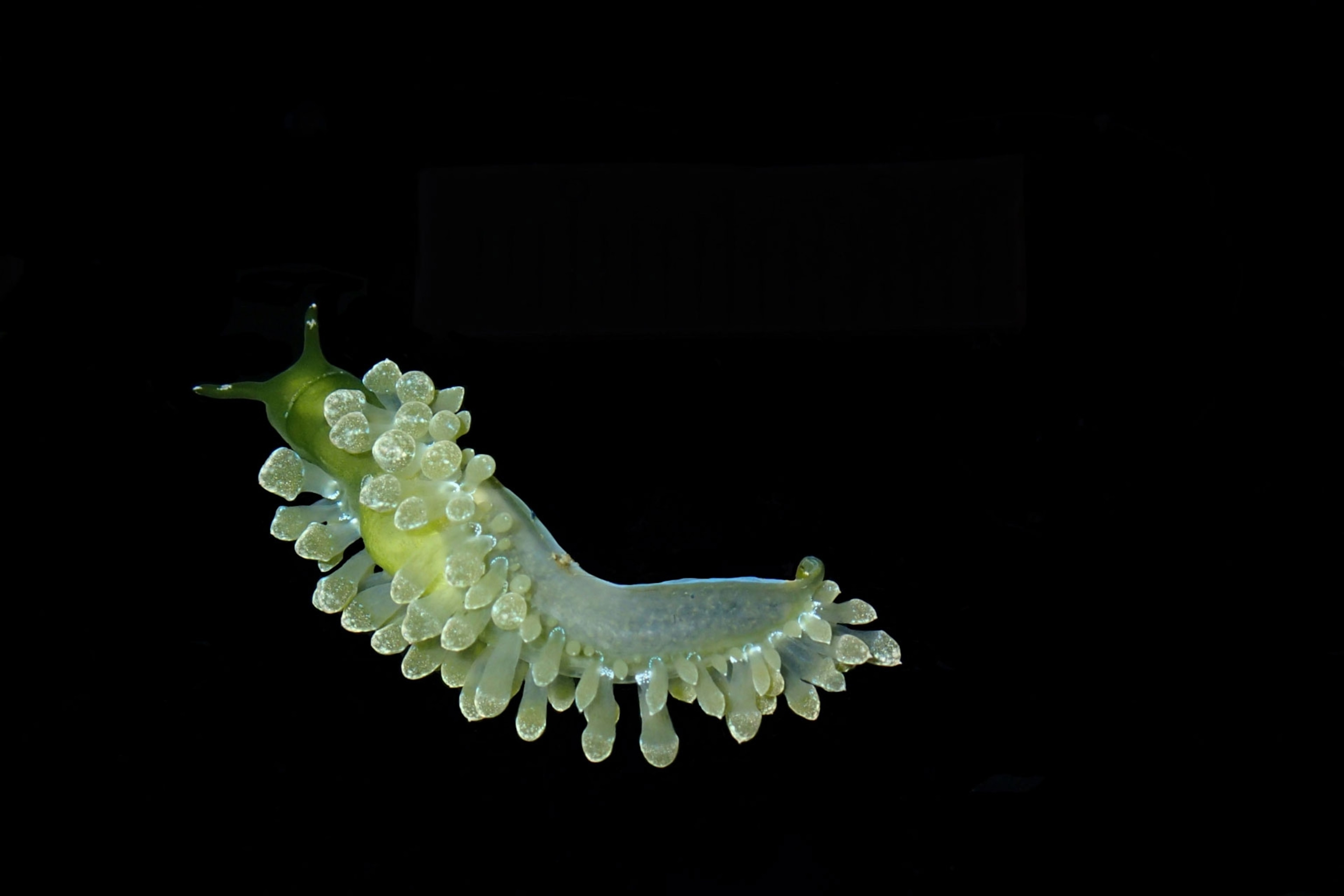

In the waters of the western Pacific drift odd bits of seaweed that look like grapes. But look carefully: Impeccably hidden sea slugs lie among this algae, cloaked in what look like green capes.

For decades, these incredible mimics were thought to be one species. But a new study shatters that preconception. Not only are these sea slugs more genetically unique than first thought, they're actually five species, not just one.

The new species, recently unveiled in Zoologica Scripta, provide a powerful example of mimicry, which is fairly uncommon among sea slugs. Those that are mimics generally impersonate other animals, and some have evolved bright colors to ward off predators. Few, if any, are as invisible—or as green and leafy—as these new masters of disguise.

“This may be the best example of an animal masquerading as a plant that we have,” biologist Nicholas Paul, an expert on seaweed and algae at Australia's University of the Sunshine Coast, said in an email. He wasn't involved with the new study.

The grapes of gnash

The new species exclusively feed on the seaweed genus Caulerpa and are found throughout the Pacific, including Malaysia, Australia, Guam, and the Philippines. Humans consider the algae's caviar-like bulbs, called sea grapes, a delicacy—but few sea creatures dare eat the stuff, making them highly invasive. Thanks to the global aquarium trade, the algae has invaded waters from the Mediterranean to Japan.

But some sea slugs can and do eat Caulerpa, none more enthusiastically than the algae mimics. They sniff the seaweed out, perching on their haunches and “dancing” in the water to catch its aroma. “Oftentimes, the habitat or food will actually trigger metamorphosis [of the slugs' larvae] into adults,” says lead study author Patrick Krug, a marine biologist at California State University, Los Angeles. “There's like a chemical dependency.”

Once the sea slugs latch onto the algae, they cut holes into its sea grapes and suck them dry, like thirsty kids gulping down juice boxes. Nearby predators wouldn't suspect a thing; the slugs' bulbous backs appear studded with sea grapes. And to complete their disguise, the sea slugs store the algae's green pigments in their skin. (Some green sea slugs are even “solar-powered.” Find out more.)

Not one but five

For decades, these algae mimics were known by just one name: Stiliger smaragdinus. But in 2015, Universiti Putra Malaysia marine ecologist Leena Wong began to think the slugs were more diverse. At the time, she was studying another slug species that feeds on Caulerpa seaweed, so she regularly collected buckets of the algae from Malaysia's Blue Lagoon. That's when she noticed the hungry green slugs crawling on the walls of her saltwater tanks. As time went on, Wong thought she was looking at two different species—but she was initially waved off.

“I wrote to a senior scientist about them, asking for professional opinion ... but was told that they are both S. smaragdinus,” Wong said in an email. “I was not convinced.”

Wong's colleague introduced her to Krug, and the pair started working together, sharing photographs and specimens. Collecting the slugs in the wild was no small feat, except for one trick: “I just collected the algae and was happily surprised when a clump of it walked away,” says Krug.

The team closely studied these slugs and preserved museum specimens, dissecting them and sequencing their DNA. It turned out that none of these sea slugs belonged in the genus Stiliger, including Stiliger smaragdinus. In fact, S. smaragdinus was actually five distinct species. Krug and Wong's team named a new genus for the bunch: Sacoproteus, after Proteus, a Greek sea god who could change his shape however he wanted.

Four of the five Sacoproteus sea slugs are algae mimics, and some match up to individual algae species. What's more, each species has unique teeth honed to pierce a different kind of sea grape. “Much like a spread of knives at a banquet setting, between them these slugs have one for each dish,” said Paul.

Now that the slugs' hidden diversity has come to light, work continues. Krug, for one, suspects that even more sea-slug spymasters are out there, waiting to be discovered.

All sea slugs are under-sampled and under-studied, he says, especially the “ones that are particularly hard to see.”