Jaguars roam throughout a massive territory, as far south as Argentina and north all the way to Mexico—and wandering males have recently been sighted in Arizona. But despite being so widespread, DNA analysis shows that the big cats are remarkably similar throughout their range, which has only been appreciated in the past few decades.

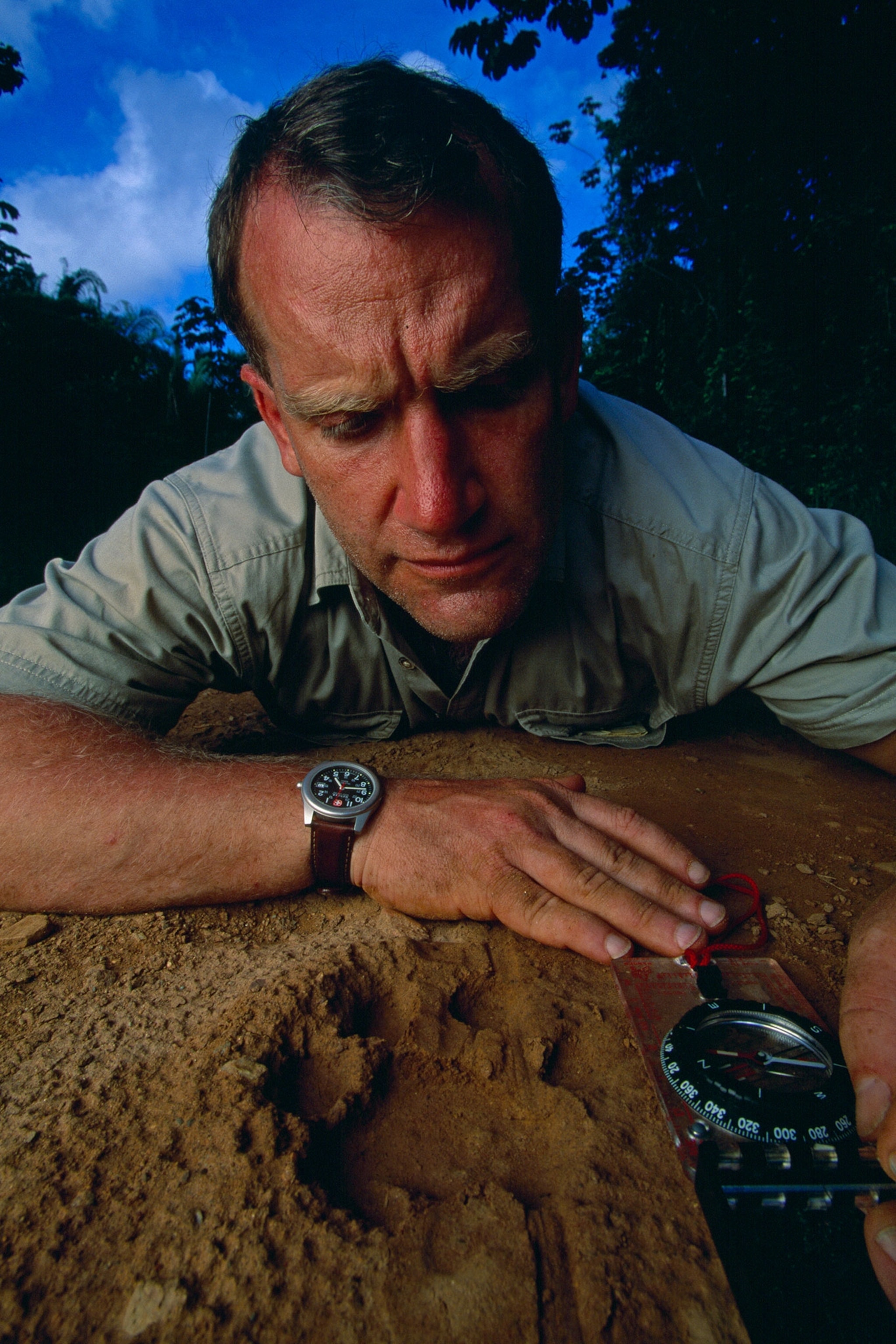

Researcher Alan Rabinowitz was one of the first to argue that this connectivity is vital, and the key to saving the animals. Prior to the idea of connectivity, the conventional thinking “was of scientists glued to a site or a region,” says Howard Quigley, Rabinowitz’s long-time friend and colleague. “Alan saw this as small thinking.”

Rabinowitz, a pioneering jaguar researcher, traveled throughout this area beginning in 2017 on a years-long campaign called the “journey of the jaguar.” The purpose of the quest was to study and protect the areas in the cat’s vast range, which spans 18 countries and millions of square miles.

If the corridor is cut up by roads and development, Rabinowitz argued, it could lead to the loss of genetic diversity in individual populations—and worse. He viewed isolation as a slippery slope to extinction, and a pressing matter.

For Rabinowitz, the journey was both the capstone to a life’s work and a personal battle with the clock. When it launched, he had already been fighting chronic lymphocytic leukemia, a form of cancer, for some 15 years. His time, he knew, was also limited.

In the winter of 2018, he had to put the quest on hold. Cancer spread through his body and, in February, he had a long surgery to remove more than 100 affected lymph nodes. Rabinowitz had hoped to present to the United Nations that March, at the largest ever meeting of governments on the topic of jaguar conservation. But Quigley had to take over. “It should have been his day in the glory light,” Quigley said. “I don’t think he really gave up until they said it was going to his lungs.”

Rabinowitz passed away on August 5, 2018; a year ago this month. He was 64.

With his death, the jaguar lost one of its greatest advocates at a moment when threats to the species and its habitat are growing. But in Rabinowitz’s absence, defenders new and old are regrouping to protect the jaguar’s dwindling range. Perhaps nowhere is both the need—and progress—more evident than where Rabinowitz’s work first began: Belize.

From stuttering to jaguars

Rabinowitz grew up in New York with a severe stutter. Human interactions were a debilitating experience, but, at the zoo, he remembers speaking freely to the animals. It was there that he formed a lifelong bond to cats.

He followed his interest in biology and became a graduate student studying wildlife ecology at the University of Tennessee. Quigley, whom Rabinowitz had met as a classmate, had been working on a groundbreaking jaguar survey and asked Rabinowitz to conduct research in a remote mountain range in south-central Belize. Almost nothing was known about the population there.

A young Rabinowitz landed in Belize in the early 1980s and settled deep in the Cockscomb Mountains, converting a small logging shack into a semi-functional home. For two years, he battled botflies, hookworms, and a litany of jungle obstacles as he trapped, collared, and tracked jaguars. With GPS a still distant technology, Rabinowitz kept tabs on his animals by mounting radio antennas to trees or even to the side of planes. On one tracking flight, the pilot crashed just shy of landing, leaving Rabinowitz and the other occupants bloody and battered.

“I thrive on adventure,” Rabinowitz wrote in his book, Jaguar, which chronicled this early work in Belize. “I was there to try and help save [the species] from extinction.”

Rabinowitz ended up advancing that goal. Using data from his Cockscomb project, he fought to convince the Belize government to protect the basin. The push led to success when, in 1986, the country named the area the world’s first jaguar preserve.

By then, cat conservation was becoming Rabinowitz’s life work. He was helping lead the jaguar program at the Wildlife Conservation Society, which he left in 2006 to co-found and run Panthera, an advocacy organization named after the genus to which the world’s big cats belong. The organization has since raised millions to support protection efforts.

Rabinowitz was, by all accounts, a larger than life figure, and his greatest contribution may have been his unique ability to bring the plight of big cats to the public. He wrote eights books, and was often featured by media outlets.

“He had a profound effect in getting the word out in a way that other scientists couldn't,” says Sharon Matola, the founder of the Belize Zoo and a long-time friend of Rabinowitz.

Protecting corridors

His work has inspired people like Bart Harmsen, who is now a jaguar expert at the University of Belize. Harmsen first read Jaguar in the 1990s, in his home country of the Netherlands. Stirred by Rabinowitz, Harmsen headed to Belize to look for the elusive cats.

Since then he’s followed remarkably closely in Rabinowitz’s footsteps. In 2003 he moved to Cockscomb where he completed jaguar surveys, tracking, and research. He even lived in Rabinowitz's old house.

Harmsen has since moved to the capital, Belmopan, to work on new threats to jaguars, like the shrinking of the Maya Forest Corridor. The stretch of forested land in the middle of the country has historically acted as the connector between northern and southern jaguar habitats.

When Harmsen first came to Belize, he said the area was still fairly wild. But he’s watched the trees disappear and the corridor narrow to a mere five or six miles in width. Even that’s bisected by a highway, with only one point where jaguars can cross. “It’s sad to see,” he says.

The corridor is primarily being destroyed by farmers, who burn and clear forests to plant crops such as sugarcane. Much of the land in the corridor is private, outside the purview of government protection. Harmsen says that while the current situation is fairly tenable, it’s fragile. The parcels of forest that are left could conceivably be sold as a single block, severing the corridor.

“Cockscomb might not be a viable population by itself,” said Harmsen, adding that genetic diversity may have to be managed by relocating cats, a prospect that riles him.

Buying pieces of the corridor is a far from an ideal conservation strategy, but at this point may be the only option. Panthera is among a host of advocates trying to raise money to purchase key stretches. In the meantime, they’ve also started relaunching the “journey of the jaguar,” with Quigley at the helm. Another priority is to combat conflict with humans.

To this end, Belize’s forestry department has established a small team of jaguar officers. At their headquarters in Belmopan, staff field calls about suspected jaguar attacks and investigate their veracity. Often it’s a false alarm, or the work of another cat such as a puma. But when a jaguar attack is confirmed, the officer documents it and tries to suggest remedies for the farmer, such as keeping livestock corralled at night.

The jaguar unit is also responsible for combating hunting and poaching. It’s illegal to have jaguar parts in Belize, and the unit has confiscated dozens of skins, teeth, and skulls. One of the officers, Shanelly Carillo, says that many people actually come to the department asking to buy the contraband. The stockpile became such a problem that they had to burn most of the skins. (Read more: on the trail of jaguar poachers.)

New solutions

There are also more niche solutions, like guard donkeys.

A farmer named Juan Herrera leads the way into the first of a series of medium-sized pastures, the last of which butts right up against virgin Belize forest. It’s from here that the jaguars emanate—or at least used to.

As of a few years ago, the farmer was suffering frequent attacks on his cows, calves, and other livestock. It’s a problem that’s common in central Belize, where farmers and jaguars often come into conflict. While Herrera says he never harmed a jaguar, many times the cats end up dead at the hands of frustrated locals.

But Herrera’s farm has been much calmer since a donkey named Napoleon arrived. The male donkey, which Panthera arranged to come to the farm in February 2015, lets out a loud hee-haw when jaguars approach, causing attacks on livestock to plummet since its arrival. “They keep an eye out for you,” Herrera says.

From research to politics

Rabinowitz’s work also helped inspire people like Omar Figueroa, who is now the minister responsible for the environment and forestry in Belize.

In the early 2000s, Figueroa was working on his PhD project in Runaway Creek, a large private nature reserve tucked in the middle of the Maya Forest Corridor, in east-central Belize. Here, he spent years trapping, collaring, and tracking jaguars in an effort to better understand their movements. But the project, he says, almost fell apart mid-way.

“All the collars failed,” he said, and he had no money to replace them. Rabinowitz eventually heard about the setback, and Panthera donated new, stronger, collars. Figueroa used them to finish his research, which provided the best data to-date on the Maya Forest Corridor. “It was Alan that got me back on my feet.”

Figueroa eventually moved from conservation to a career in politics and his current position, where he is working to raise awareness about the biological value of the Maya Forest Corridor.

“The development pressures that are facing the Maya Forest Corridor have been increasing,” said Figueroa. “You can see tremendous changes occurring.”

Valuing the cats

Figueroa and the jaguar officers are far from the only Belizeans working to help jaguars. Harmsen, for one, is heartened to see local communities increasingly taking the reigns of jaguar conservation in the country.

Every Belizean child takes a school trip to the zoo at some point, where they get to meet the country’s most famous jaguar, named Junior Buddy. He’s known across the country and even appeared on the 2011 edition of the national phonebook.

Panthera is currently helping support two young Belizean graduate students studying in Mexico, with the hope that they will return after graduation. But time remains of the essence.

“Belize has recognized that the clock is ticking,” said Figueroa. “The window of opportunity for us to secure connectivity in the Maya Forest Corridor is closing fast.”