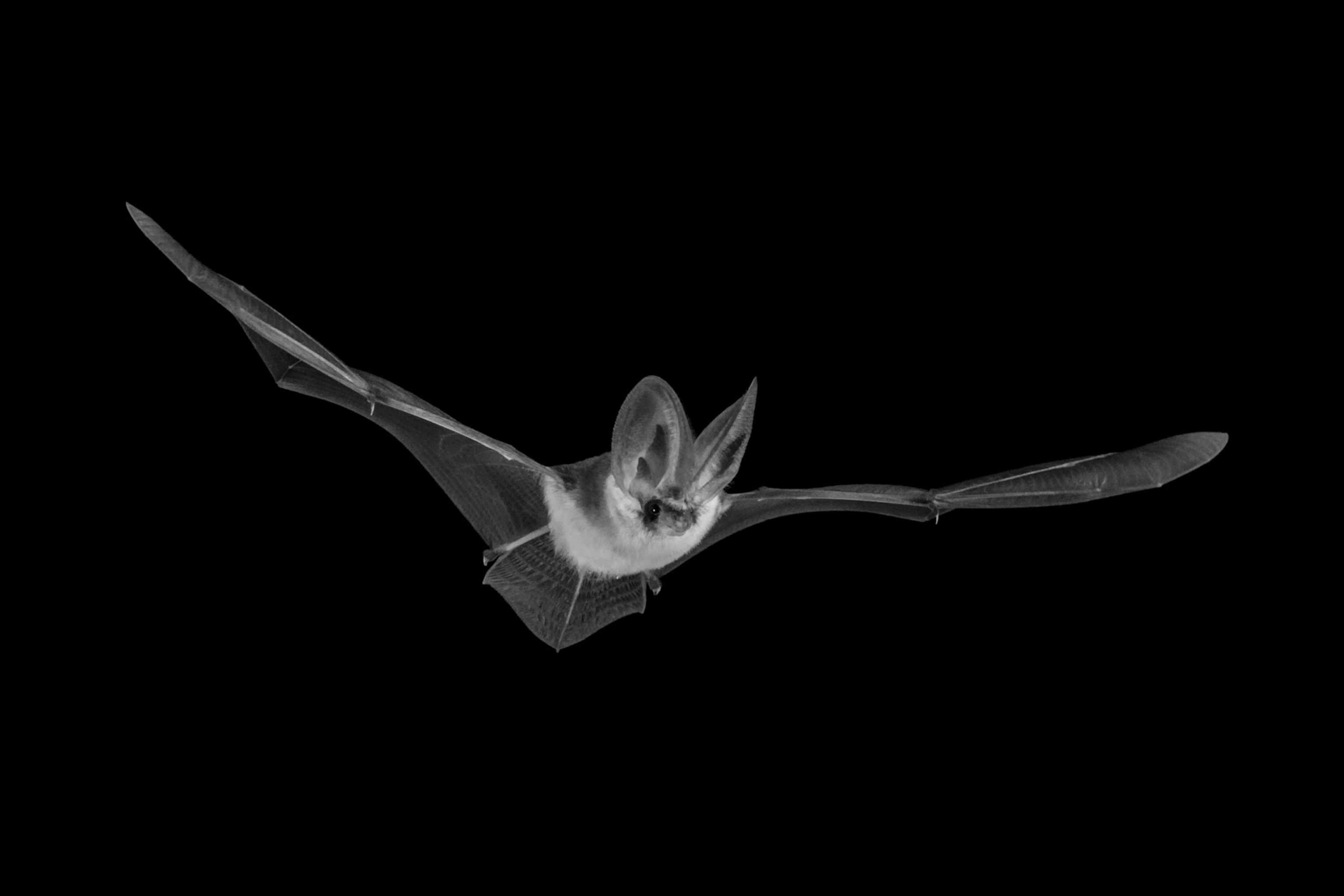

In an old stone barn on an organic farm in Devon, England, live lesser horseshoe bats, noctule bats, whiskered bats, and more. Each night during the summer, they emerge from their maternal roost to hunt for moths, flies, and other insects. For nearly two months last summer, they had an audience.

A few nights a week, conservation photographer Neil Aldridge posted himself in the grassy courtyard nearby. One of his cameras pointed into the barn door and other pointed up into the night sky. Prepared to stay up all night, he configured his cameras to snap photos the instant a bat triggered a motion sensor.

If he was lucky, when he reviewed the photos later, Aldridge would find that he captured one of Britain’s rarest bat species in flight: Plecotus austriacus, or the gray big-eared bat.

“Every shoot we got closer,” says Aldridge, whose patience paid off. “I was almost getting the shot, and refining it bit by bit. Eventually the last two shoots were where I ended up getting the two key images.”

The photos are part of Back from the Brink, a project working to save some of England’s most threatened animals by uniting conservation organizations to promote species recovery. As part of the project’s gray big-eared bat effort, Aldridge’s job was to capture photos of the enigmatic species to help the public learn more about them.

Fewer than a thousand

Also known as “whispering bats,” gray big-eared bats—so named for ears that are as nearly as long as their bodies—have evolved to echolocate more quietly than other bats, helping them hunt. But it also means that researchers’ bat detectors—devices that convert bat calls into frequencies humans can hear—have a tough time picking up on their soft, occasional sounds. This leaves the species little studied, poorly understood, and rarely photographed. (Read more: Six bat myths busted.)

As few as a thousand live in England today, making it the second-rarest bat species in the United Kingdom; only the greater mouse-eared bat—just one is believed to remain—is rarer. Most gray big-eared bats are found in southern Europe, from Portugal to Romania, but their numbers are generally declining across the board.

The sharp population drop in England began about a century ago. Changing farming practices led to the disappearance of some 90 percent of England’s meadows, eliminating prime hunting habitats for the bats, which eat moths and flies. Such habitat loss also limits bats’ role as natural pest suppressors, causing some farmers to use more pesticides, which further harms the bats, and so on.

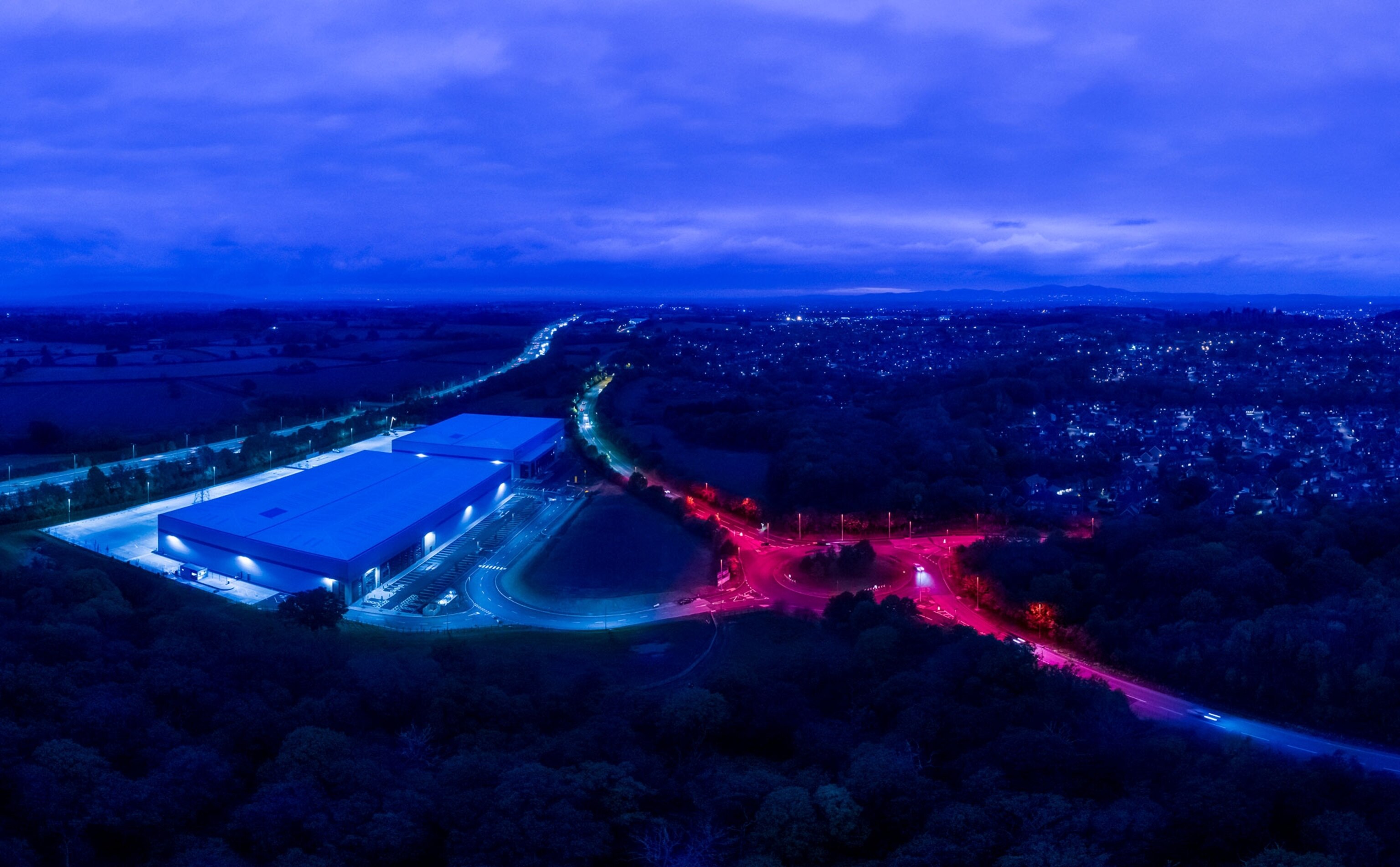

Because bats are nocturnal, streetlights are an additional threat, disrupting their flight as they access new roosts and feeding grounds. The species has also suffered from the loss of maternal roosting sites as the U.K.’s traditional stone barns—the bats’ preferred sites to give birth and raise pups—have been converted to rural homes. Fewer than 10 known bat maternity roosts housing the species, all in southern England, remain. (This is how light pollution harms urban bats.)

But in a surprising twist of fate, climate change, which affects rain patterns and temperature, may herald a return for the species, says University of Exeter’s Orly Razgour, an ecologist and conservation biologist who studies how bats and other animals respond to changing environments.

“Climatic conditions are going to become much more suitable [for gray big-eared bats] in the U.K.,” she says. “This species is likely to expand further north, while losing a lot of its current suitable habitats around the Mediterranean.”

By encouraging the development of wide corridors of meadows and grasslands, conservationists aim to physically link the bats’ current habitats in southwest England to other areas of the country that may be suitable habitats in the future.

Sustainable for all

To ensure his photography didn’t disturb the bats, Aldridge turned to the Bat Conservation Trust for guidance. He learned that bats aren’t bothered by red light in the way they are by white light, so he used red filters to avoid startling them.

While Aldridge focused on his photography, members of the Bat Conservation Trust spoke to farm owners about land management. Craig Dunton, Back from the Brink’s gray big-eared bat project officer, says one goal is to encourage landowners to develop suitable bat habitats, which may involve planting wildflower seed to enhance existing grasslands, planting hedgerows, and practicing organic farming with limited pesticide use. Most farmers were willing to accommodate such changes.

“A healthy natural environment is a really important precursor to having a successful, sustainable farming business,” Dunton says. “We need the natural environment to be part of our food systems. We need pollinators; we need bats to suppress pests; we need to have a more holistic view.” (In May 2020, National Geographic magazine investigated: Where have all the insects gone?)

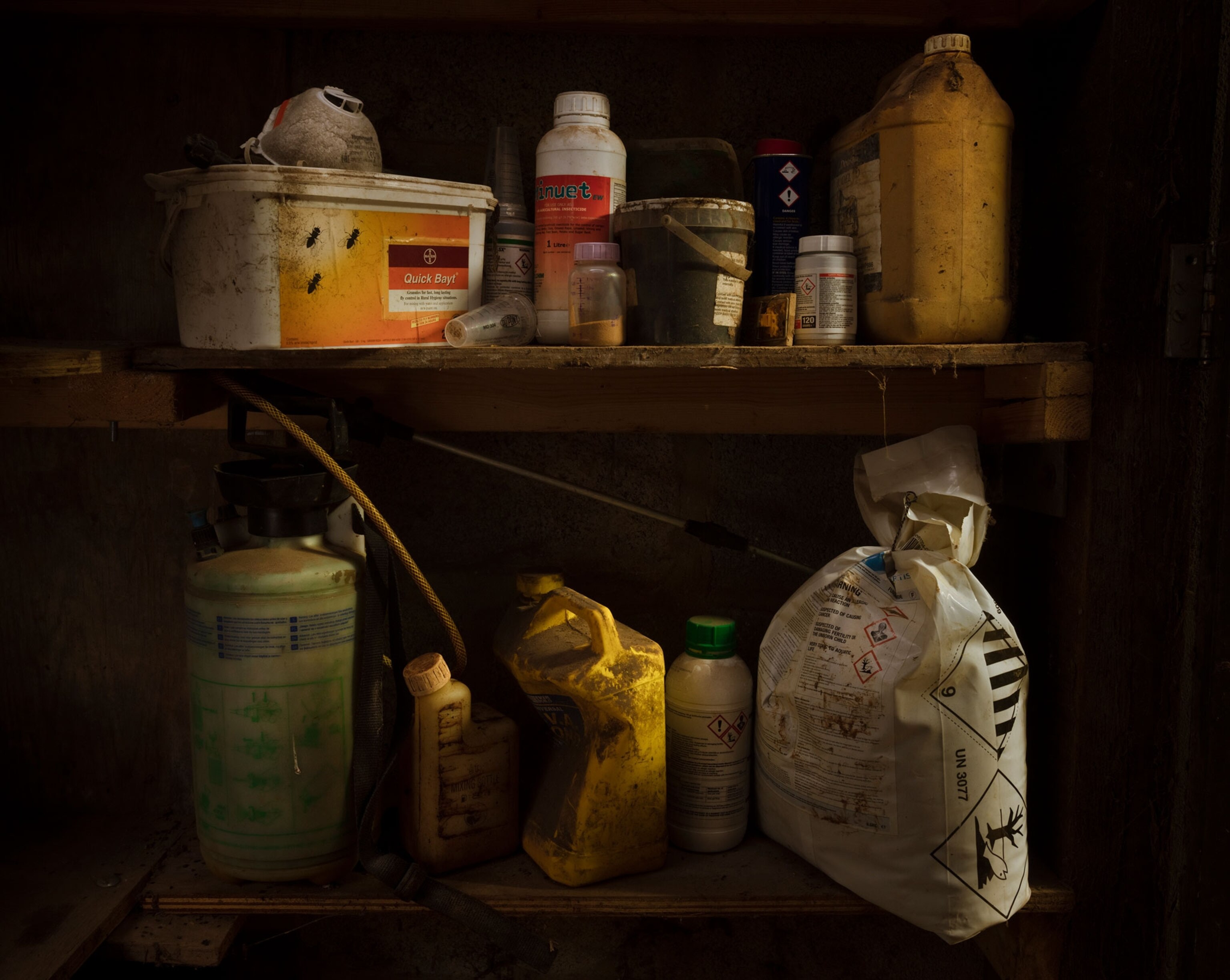

Aldridge also photographed pesticides in North Somerset, which highlighted for him the threat they pose to bats and their habitat. “I was in a dark room with no ventilation, no windows, surrounded by bags and tubs of stuff that had warning signs on it, a lot of which says, ‘known to cause cancer,’” he says. “And you think: We’re putting this in the landscape.”

While he was gratified to document rare bats in their natural habitat, Aldridge says his goal is to do more than take a pretty picture. “If we get it right for the bats, if we can change their fortune and their future, then we’ll change it for so many things.”