A 50-day voyage to the kingdom of ice

National Geographic joined an expedition to understand the mysterious creatures of the ice-locked southern continent.

Off our bow, sharp-etched in the summer sunlight of January, towers a wild gaunt island of black cliffs and glacier-cloaked mountains. Icebergs drift all around us, a stark white fleet riding an ink-blue sea.

Across half the horizon, south and east, marches a jagged succession of snow peaks. They seem only a few miles off, but our chart shows that they lie more than 50 miles away. They stand on the Antarctic Peninsula, the long, beckoning finger of the Antarctic Continent that reaches north toward Cape Horn and South America.

I brace between bulkhead and hatch rail to keep from sliding across the ice-lookout house. Belowdecks, cans crash from stowage shelves and the cook shouts dark oaths. Each time we roll, water cascades over the side onto the weather deck.

The stubby little trawler flies a blue flag with the initials USARP—U. S. Antarctic Research Program. Her name is Hero.

"Hero is wet, cramped, and uncomfortable as a bucket in a heavy sea," Philip M. Smith, deputy head of polar programs for the National Science Foundation, had told me in Washington, D. C., weeks before. "But you'll see a lot of the peninsula by living aboard her. She's hard used—always on the go."

How right he was, I think, as I hang on.

For more than a month I've ridden Hero as she roved hundreds of windy miles, carrying Antarctic researchers from outpost to outpost along this icebound coast. Now, on yet another scientific foray, she rolls and yaws along, driven by two rumbling diesels. She carries two stout wooden masts, with heavy orange sails furled to her booms. Timbered of thick oak and Guyana greenheart, sheathed at the bow with steel ice plating, she sails alone in this far-southern realm of sudden storm and uncharted rock.

Yankee skipper sights a forbidding land

Through these waters, just 150 years before, another wooden ship named Hero sailed south. Only 47 feet long (we measure 125), she was the scouting sloop of a sealing flotilla from Stonington, Connecticut. Her captain, Nathaniel Brown Palmer, was 21 years old.

Historians are not sure who first saw and recognized the mainland of Antarctica, last of earth's continents to be found. Nat Palmer has been credited with the discovery, just north of the Antarctic Circle, that southern summer of 1820-21. But so have two British mariners, Edward Bransfield and William Smith, who were there earlier in 1820.

All through the off-lying South Shetland Islands that year, American and British ships and shore parties were hunting—and nearly exterminating—the southern fur seal. Any of them could have seen Antarctica.

Two Russian exploring ships, the Vostok and the Mirnyy, reached these waters in January 1821, under Capt. Thaddeus Bellingshausen. He was startled to find eight or nine sealing vessels anchored in one strait, and he met and spoke with Palmer.

Years later Palmer recalled that Bellingshausen, upon learning the extent of the young American's discoveries, exclaimed to him:

"What do I see and what do I hear from a boy... that he is commander of a tiny boat the size of a launch of my frigate, has pushed his way... through storm and ice, and sought the point I... have for three long, weary, anxious years searched day and night for? ... What shall I say to my master [Czar Alexander I]; what will he think of me?"

Science mounts a peaceful assault

Today ships of many flags ply the same freezing, treacherous waters that Bransfield and Smith, Palmer, and Bellingshausen sailed. Scientists of five countries huddle in small shore bases through black Antarctic winters.

In the past 15 years a great invasion of Antarctica has occurred. It was sparked by the International Geophysical Year of 1957-58. A dozen nations, joining in that far-reaching study of our planet, sent teams of scientists to the ice-locked southern continent.

"The project proved so successful, its findings so important, that the joint assault on Antarctica has continued ever since," Dr. Louis O. Quam, acting head of NSF's Office of Polar Programs, told me. "Many of the IGY bases are still manned."

In 1959 the Antarctic Treaty was written and signed, reserving the entire continent for peaceful pursuit of scientific knowledge. Today 16 nations abide by that treaty.

On the Antarctic Peninsula, Dr. Quam said, men have lived longer, in a greater number of stations, than anywhere else in Antarctica. More than two dozen major bases, plus numerous small refuges, have been built there since 1900. Argentina, Chile, and Great Britain established most of them, originally to support overlapping territorial claims. The Antarctic Treaty set those in abeyance for at least 30 years. More recently, both the United States and the Soviet Union have built year-round research bases on islands just off the peninsula.

Yet, oddly, this first discovered and longest inhabited part of Antarctica remains little known to the outside world. Nor has it been changed appreciably by man's coming. After a century and a half, it remains a region scaled for another world, another time.

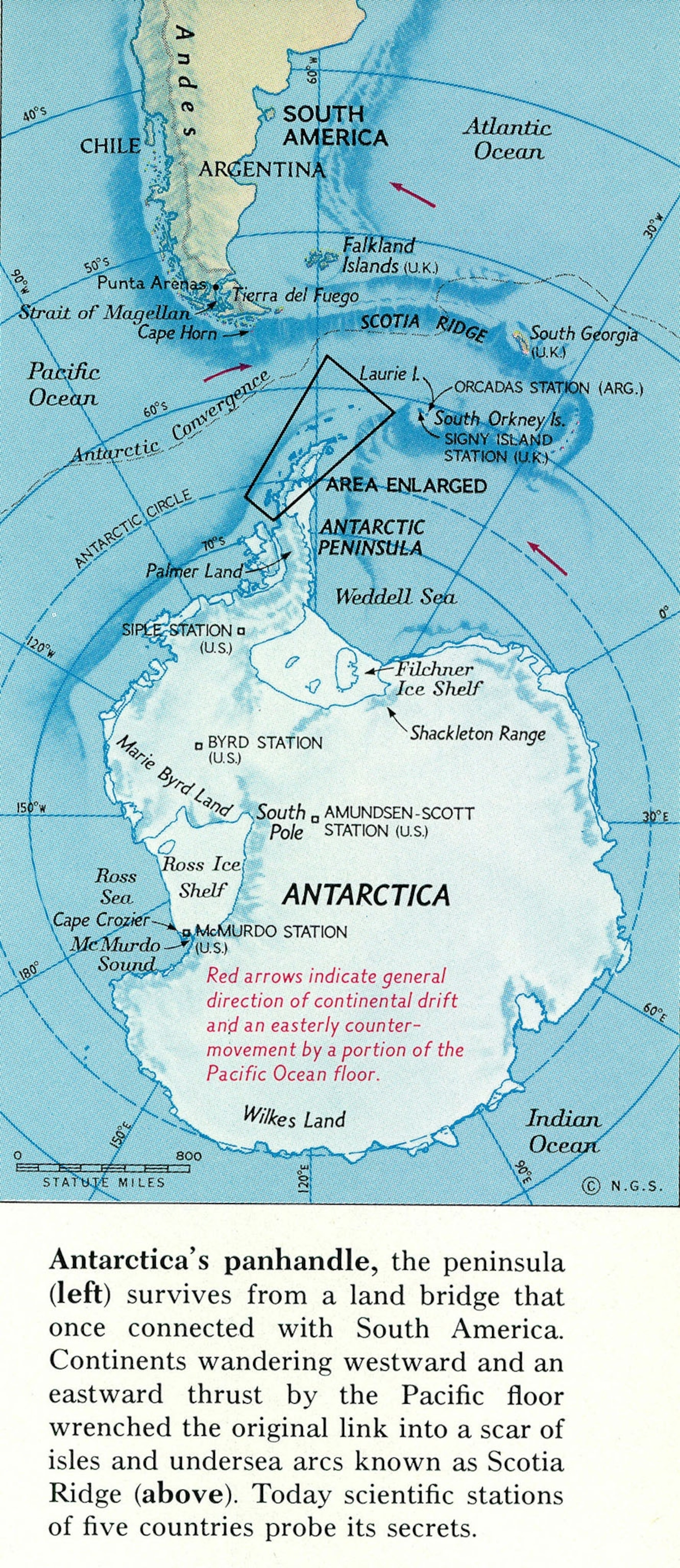

To reach the peninsula, one must go by sea. An extension of South America's Andes, it and its fringing islands are basically a jagged chain of peaks thrusting up from the ocean, mantled by glaciers and edged by ice shelves. The northernmost tip lies 600 nautical miles southeast of Cape Horn, across a strait seamen fear as the stormiest in the world.

The Drake Passage lay flat calm, however, the week I first crossed it. From Punta Arenas, Chile, on the Strait of Magellan, I sailed south aboard the 133-foot biological research ship Alpha Helix, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California.

Porpoising schools of Magellanic penguins and piebald dolphins escorted us, and seabirds wheeled around us—black-and-white Cape pigeons, wandering albatrosses, snowy Arctic terns, tiny flittering Wilson's petrels.

Sudden fog announces a key boundary

On New Year's Eve we nosed into fog as sudden and thick as a smoke screen. "The Antarctic Convergence," said Alpha Helix's lanky gray-bearded captain, Robert B. Haines. "Cold water from the south, meeting warmer Atlantic and Pacific surface water. Presto, fog." To scientists, this meeting of waters is the true boundary of Antarctica, rather than its ice-locked shoreline or the 60th parallel specified by the Antarctic Treaty.

On our fifth day out, with the convergence far behind us, I climbed to the bridge at 3 a.m. to watch the sun rise above a mountain notched horizon. Alpha Helix was sailing close under a low, rounded snow dome that caps the southern end of Anvers Island, a quarter of the way down the peninsula.

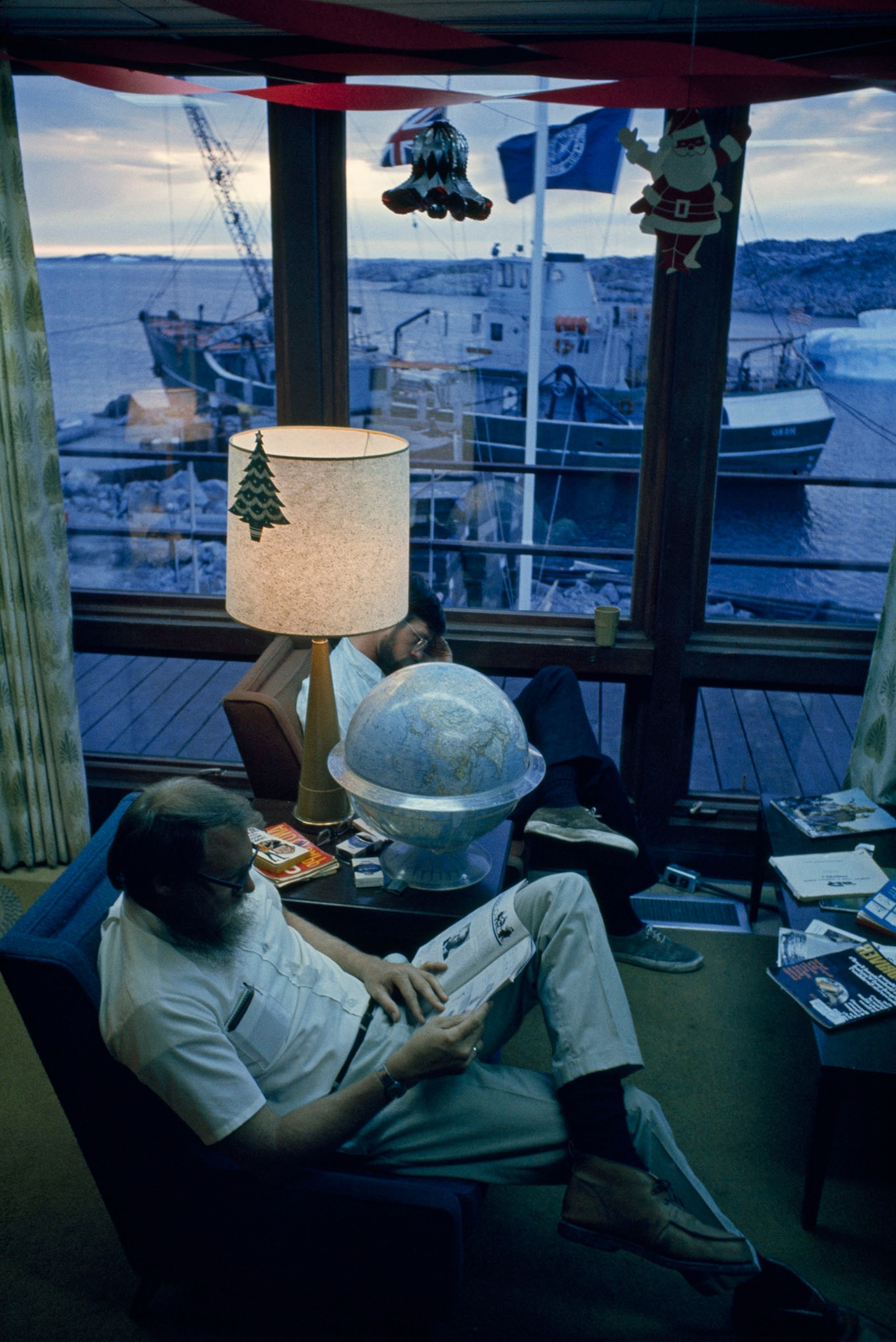

"Keep a close watch in there." Bob Haines handed me his binoculars. I caught a flash of sun on glass. Against the glacier, screened by rocky islets, lay two buildings and two oil tanks—Palmer Station.

Palmer is one of four year-round U. S. Antarctic bases operated jointly by the National Science Foundation and the Navy. The other three this year are McMurdo, the big supply center and air crossroads on the Ross Sea; Amundsen-Scott Station at the South Pole itself; and Byrd Station, buried in cavernous ice tunnels in Marie Byrd Land. A new wintering-over base, Siple Station, will be opened in the southern summer of 1971-72, and Byrd Station will be closed.

"Of them all," Phil Smith of NSF had told me, "Palmer is in many ways the most isolated, even though it's the northernmost. Without aircraft contact, with supplies and new personnel coming in only once a year by slow ship, it has precious few links with any of our other stations, except by radio."

But for work on and along the jagged coastline and island fringe of the peninsula, it has the Hero. Owned by the National Science Foundation and operated by a civilian crew, Hero bases at Palmer three to four months a year, before storms and pack ice force her back to South America. Now I saw her for the first time. She lay at a short steel bulkheaded jetty directly in front of the main station building, which stands on a rocky spit protruding from the ice.

Robert L. Dale, USARP representative for the peninsula, and Lt. (jg.) Don McLaughlin, the young Navy officer in charge at Palmer, welcomed Helix's newcomers.

"Please don't go up on the glacier without a guide," Bob Dale warned. "You can fall into a crevasse before you know it's there. We're here to help you in your research in any way we can—but we'd rather not have to do it with rescue ropes and stretchers."

Science in Antarctica today is no longer a lonely struggle by rugged explorers driving dog teams (though the British still prefer dogs), or by ships beset in pack ice (though this, too, still happens). Instead, at shore stations and on shipboard, I saw men probing science's frontiers with the most sophisticated equipment. More than two dozen scientists worked at Palmer and from the Alpha Helix and Hero last summer.

Gerald L. Kooyman of Scripps is a quiet young physiologist who has spent seven summer seasons in Antarctica, "chiefly studying seals, on and under the ice of McMurdo Sound," he told me. Joseph Peter Schroeder, tall and ebullient, is a veterinary surgeon from Solana Beach, California.

Together, Jerry Kooyman and Pete Schroeder had come to Palmer aboard Alpha Helix to learn what happens in the bodies of penguins and other Antarctic birds when they dive deep into near-freezing water for their food. They had brought a heavy steel pressure chamber with them, as well as sensitive blood-sample analyzers and heartbeat recorders. Within a few hours of our arrival, they were hard at work.

I rode with them in a slow-chugging motor whaleboat out to Cormorant Island, one of many clamorous, strong-smelling rookeries that lie near Palmer. Against a porcelain-blue sky, Mount William on Anvers Island soared to a snow-corniced peak 5,000 feet above us. The sea was smooth, sun washed, and spotted by swimming birds that vanished and reappeared as if by magic.

"Blue-eyed shags, a kind of cormorant," Jerry said. "They're fishing—diving and out swimming their catch. But we don't know how far down they go, or for how long....

"There!" Like a string of jack-in-the-boxes, another raft of birds abruptly popped into view. Jerry looked at his stopwatch. "Well over a minute, if they're the same ones."

The sea-sculptured rock crag where we landed held thousands of little Adélie penguins, all cackling stridently at their fuzzy gray chicks. Nesting side by side with them were the shags, which seemed at first glance to be penguins with long necks.

Penguins don't fly—except through the water—but the cormorants wheeled and dived around the rookery islet, landing and taking off from the sea like underpowered old flying boats. Jerry and Pete set up a movie camera to record their comings and goings. As shags returned, craws filled with half-digested fish for their young, their arrivals were unbelievable. Swooping straight in, wings widespread, webbed feet extended, they would crane their necks downward as if awaiting a landing officer's signal, then suddenly pitch down, each to its nest.

The penguins paid them no heed. But they screeched and pecked indignantly whenever we—or another penguin, or a gull-like and predatory skua swooping overhead—ventured too close.

Penguins ride a watery elevator

In the days that followed, a succession of shags and penguins—Adelies and red-beaked gentoos—took trips for science to Palmer's laboratory. Wired for heartbeat and strung with blood-sampling tubes, they found themselves inside Jerry Kooyman's diving chamber.

Pete worked a hand pump to "dive" the birds to pressure-depths as great as 200 feet. Every 30 seconds, Jerry Kooyman took blood samples from tubes leading inside the chamber; an electrocardiograph spewed data on heartbeat. The readings complete, a pump sucked out the seawater, the penguins were released unharmed, and eventually went home to their own world.

"Someday," said another Scripps biologist, Dr. H. T. Hammel, "our human attempts to live and work deep in the oceans may be helped by knowing better how penguins and seals thrive in seas as cold as this.

"My own specialty is making animals think they are hotter or colder than they really are," he added. For hours I watched his patient, gentle work with penguins in one of Alpha Helix's superbly equipped laboratories.

By inserting hair-thin water tubes into the temperature-control center of an anesthetized penguin's brain, the physiologist was able to trigger and study his subject's normal reactions to extreme heat and cold.

When warm water circulating through the sealed tubes in their heads made them feel hot, the penguins held out their flippers, panted, and ate ice—even though the ice bath in which they lay already had cooled their bodies below normal. Conversely, when the brain's temperature center was cooled, the penguins shivered violently, even while standing in hot water.

Another of Ted Hammel's contrivances was a motor-driven canvas belt, running on rollers within a wire-mesh enclosure. Here his penguin subjects waddled briskly along, hour after hour, getting nowhere but yielding readings of their body temperature and blood flow during protracted exercise.

As Dr. Hammel's birds trudged on, Alpha Helix's projects at times resembled a five-ring circus. A University of Washington team fitted penguins with yellow vests that carried radio-telemetering transmitters. Released on their nesting grounds, the birds broadcast blood-flow data into a recorder. Two UCLA scientists fed other penguins miniature transmitters the size of rolls of mints, and from a tent on the rookery listened to changes in their body temperatures.

A senior Scripps physiologist, Dr. Per Fredrik Scholander, who designed Alpha Helix as a world-ranging biology laboratory, studied the oxygen-carrying capacity of penguin muscle tissue.

"These are all bits and pieces of basic knowledge," he told a shipboard seminar, "that help us better understand life itself."

Hero fishes for "gaping head"

Through these long sun-filled days, Hero went out each morning in search of one of the most unusual creatures in Antarctic seas. She was having little luck catching Chaenocephalus (meaning "gaping head") aceratus.

"Commonly known as the ice fish," said Dr. Edvard A. Hemmingsen, a Norwegian who led Alpha Helix's scientific team. "It and other species of this Antarctic family are the only vertebrates that have no red cells in their blood—no hemoglobin, which in most animals carries the oxygen essential for life."

He wanted to study the ice fish's breathing and cardiovascular systems—but the fish was elusive, and Dr. Hemmingsen was becoming anxious. "We go farther," he decreed. So I moved from Alpha Helix to a berth aboard the Hero, to sail with her on a long-distance trawling expedition.

We stood north through the spectacularly beautiful Gerlache Strait, named for the first scientific expedition to winter over in Antarctica—a party under Belgian Adrien de Gerlache, whose ship Belgica was beset in the ice in 1898. Its first mate was Roald Amundsen, who 13 years later became the first explorer to reach the South Pole.

Mountains fell sheer to the sea on both sides of the strait. Hero butted her way through broken pack ice, leaving smears of red bottom paint on the white floes. A pod of fin whales, each 50 feet long or more, blew and rolled past us. Killer whales raced alongside, their high, sharp fins outpacing Hero's plodding nine knots.

Off Brabant Island, under the massive 8,274-foot pyramid of Mount Parry, Dr. Hemmingsen found his ice fish. Again and again Hero's big trawl went over the side, dragging along the bottom 300 feet down. Each time it came up, it held one, or two, or even four ice fish. One to two feet long, their pale-gray bodies seemed half mouth, usually wide open.

"Get them into the tanks quickly," Ed Hemmingsen warned. His grin was as wide as that of the fish.

"If we can learn in detail how the ice fish transports oxygen without hemoglobin," he told Hero's hardworking crew, "it will increase our understanding of respiratory functions in general. We may even get clues that could aid in the development of artificial blood—an emergency substitute, so to speak, that could be used for a limited time."

Two days later, as we came slowly around Bonaparte Point into Palmer, we could see the foretops of two large ships lying in Arthur Harbor—the white, broad-beamed U. S. Coast Guard icebreaker Westwind, and a bright-red hydrographic ship of the Royal Navy, H.M.S. Endurance. Behind them Alpha Helix swung at anchor.

There was also a totally unexpected newcomer—a slim, high-masted sailing yacht, blue and buff, flying the Stars and Stripes. And ashore in Palmer's paneled mess hall and lounge were six strangers—including a woman.

Skipper of the 53-foot Awahnee was a burly, grizzled, squint-eyed romantic named Robert L. Griffith, a retired veterinarian from California now living in New Zealand. With him were his wife Nancy—small, freckled, and friendly—their 16-year-old son Reid, and three young New Zealand crewmen.

"We built Awahnee ourselves, of ferrocement—steel mesh and mortar," Griffith told Palmer's incredulous Navy complement. "We've been around the world three times in her—but this time with a difference."

By sailing almost entirely below 60° south, Griffith said, they were retracing as closely as they could the historic circumnavigation of Antarctica by Britain's Capt. James Cook between 1772 and 1775.

"We left Bluff, New Zealand, on the tip of the South Island, 30 days ago. We have a small auxiliary engine for emergencies, a battery radio, and a sextant and compass for navigation. We plan fewer than a dozen land falls in 12,000 miles. By staying down close to the ice, out of the roaring forties and furious fifties, we miss the really bad winds. So far, we've averaged 155 miles a day at sea."

"We don't need a refrigerator aboard on this trip," Nancy answered a question about fresh food. She added cheerfully, "And this time I really don't mind being sent below to cook. The galley is the warmest place on the boat."

"I think this ... to be a continent"

Next day Arthur Harbor filled to the bursting point. The big gray Navy cargo ship Wyandot, veteran of many voyages into the ice, came in from Valparaíso, Chile. She brought a new work crane for Palmer, a year's groceries, and half a dozen more scientists. Aboard also were Dr. Quam, chief of USARP, and retired U. S. Ambassador Paul C. Daniels, who helped draft the Antarctic Treaty and signed it for the United States.

A few days later Dr. Quam and Ambassador Daniels sailed with Hero and Alpha Helix for a goodwill visit to Argentina's nearby Almirante Brown Station. Thus it was that on February 7, 1971, an Antarctic anniversary was commemorated.

"Only about 60 miles north of here, the first men to set foot on the Antarctic Continent landed just 150 years ago," Dr. Quam had told a group of us at Palmer Station. "They were a party of sealers from the American schooner Cecilia, Capt. John Davis of New Haven, Connecticut, master."

Captain Davis noted in his log for that date: "I think this Southern Land to be a Continent." Twenty years later a United States exploring expedition under Lt. Charles Wilkes proved him right.

Geologically as well as historically, the Antarctic Peninsula that Wilkes helped define is young. Its seagirt mountains crumpled and uplifted only in the past 100 million years. "And parts of it are still being violently reshaped," Dr. Quam said with a certain understatement.

Hot spot on Antarctica's rim

Deception Island in the South Shetlands, like a number of other places on Antarctica's rim, is an active volcano—so active that it has erupted three times in the past four years. A famous old sealing and whaling port, Deception held three year-round stations—Argentine, Chilean, and British—until it erupted in December 1967, again in February 1969, and most recently in August 1970.

In a heavy swell, rising wind, and snow, Hero came to Deception at three o'clock one morning. Sheer cliffs of black and red rocks, vanishing upward into the overcast, framed a narrow entrance in its forbidding coast.

"Hells Gates, Dragons Mouth, Neptunes Bellows—you can find it under all three names in old sailing directions," said Hero's Capt. Richard J. Hochban. "And little wonder—look at it!"

We hugged one side of the surf-washed gap; against the opposite face, canted and broken in two, lay a rusted old whale catcher. Then, suddenly, we were inside the island, in a five-mile-long bay stretching away into the driving mist. The wind whistled off black slopes and drove whitecaps across the great caldera. For that is what forms Deception's central bay, Port Foster—the collapsed cone of a huge volcano, a jagged, ice-covered ring of rock enclosing one of the finest harbors in Antarctica.

Here, in shore-whaling days of the early 1900's, Norwegians by the score cut up blubber each summer on a wide beach for an evil smelling tryworks, whose ruins still stand. Later, in the 1920's, as many as eight ocean liners, converted to whale factory ships, lay moored at Deception at one time. It was a port of entry to Antarctica, with a British magistrate and regular mail service.

In the dawn gloom Hero slid past Whalers Bay to another cluster of low abandoned buildings across the harbor. There she lay to and blew her whistle, raising rolling echoes.

Camped at Argentina's Decepción base, three glaciologists—a Norwegian, an American, and a Russian—awaited our coming. Olav Orheim and Terence Hughes, of Ohio State University's Institute of Polar Studies, and Leonid Govorukha, from the Soviet Union's Arctic and Antarctic Scientific Research Institute at Leningrad, had been working on the island for nearly two months, studying its glaciers and the effects of the recent eruptions. They were the last still there of an 11-man scientific party landed by an Argentine ship and supported by Chile, Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

They were grimy, tired, and very glad to see Hero. "We could use a hot bath," said Olav Orheim as the trio clambered over the rail. Dr. Govorukha, smiling widely through a bristly black beard, added a fervent "Da, da."

They were already in the showers, and their ash-caked clothing in the ship's washing machine, as Hero swung back to a sheltered anchorage in Whalers Bay. There we found we had company—an oddly rigged yacht flying the Italian flag. Her two short masts and slanting yards were those of an Arab dhow—lateen, in sailors' terminology.

San Giuseppe Due—St. Joseph II—had arrived at Deception ten days before, her captain, Giovanni Ajmone-cat, told us that night in their dark-varnished main cabin. He and his amateur crew of three were making a two-year voyage around the world.

Only the captain spoke any English. So our gam that night in the old whalers' harbor consisted of an odd mixture of Spanish, French, Italian, Russian, and English. The Italians were trying in vain to contact Rome with their shortwave radio. "Roma... Roma ... Roma . .. Roma ... barca San Giuseppe Due, Antarctica..." the captain shouted through the static.

The answering silence daunted them not a bit. Far from home, these adventurers were anxious only to be on their way, west across the Pacific to Australia, before winter caught them too far south.

Eruption bares island's icy diary

The glaciologists' study was not yet complete; Hero was there to lend them support. So for two arduous weeks that followed, photographer Bill Curtsinger and I joined the scientists at their work.

Doing our best to keep up with the wiry, untiring Leonid Govorukha, we slogged and labored up mountainsides of ice buried under deep layers of black ash thrown out by Deception's three recent eruptions. In 1967 the deluge pelted the three scientific stations at Deception and forced their evacuation by helicopters from rescue ships.

"Fourteen months later, early in 1969, more vents exploded, opening a three-mile-long rift," Olav Orheim told us. "A flood of hot mud and rock utterly destroyed the Chilean base. Six men who had returned to the British station had to run for their lives with iron sheets held over their heads."

No one remained on Deception for the 1970 blast. That eruption blew a chain of craters, one of them a quarter of a mile wide and 400 feet deep, through solid ice. On the ice cliffs thus exposed, the three glaciologists were reconstructing the history of Deception by charting the successive layers of ice and ash built up over the years.

"We have read back already to the mid-1700's," Olav said. "The glaciers show many eruptions that historians missed. In 1842, for example, a sealing captain reported seeing the whole south side of Deception on fire, with 13 volcanoes in action, but no one believed him. We know now that Deception had a major eruption that year."

Steam rose from the base of the great rift slashing across the mountainside. A deep cave had melted out beneath the glacier.

"Vkhod v ad!" Leonid Govorukha described it. "Doorway into hell!" As we tried to scramble down into the cave, the heat drove us back. An earlier measurement, Olav said, had placed the rock temperature there at nearly 500° Fahrenheit. Hades indeed!

Unbroken snow cloaks hidden hazards

Another day, on another glacier, Olav and I both fell through doorways into danger.

With Terry Hughes, we had roped together to cross a deceptively smooth snow slope, to remeasure ice-movement stakes set out two years before. Olav stabbed carefully with the point of his ice ax as we crossed a 1,200-foot high ridge. Then, suddenly, he disappeared. Where he had stood a second before, only a small hole in the snow remained. The rope led to the edge of the hole, and Terry was desperately braced, his feet straight out ahead of him in the snow.

"Crevasse," he grunted as I helped take up the strain. With the rope anchored to our ice axes, Terry slid forward headfirst to peer down the hole. Olav had dropped more than 30 feet into a narrowing cleft in the ice; his feet were jammed into the crack.

Undaunted, he yelled instructions to us: "Hold the strain on my lifeline, and drop another rope with a bight in it."

Laboriously, he worked the loop over one foot, then loosened his lifeline and passed a loop around the other foot. Then, alternately heaving and holding, Terry and I helped him walk his way to the surface. The process took more than half an hour.

Minutes later, I knew what he had experienced. As we marched single file back across the ridge, gingerly following our original footprints, the world dropped out beneath me. Suddenly I was swinging wildly in an icicle-walled pit that yawned below into total darkness.

Although Olav and Terry were less than forty feet away, the snow muffled their shouts, and mine to them. It was as if I had dropped into a soundproof void.

Then Olav's face appeared in the hole above me. "Are you O.K.?" I heard him call.

"Yes. But I think my sunglasses are still falling. That's a long way down."

"Can you swing over to that ice knob?"

"I think so... yes. Now what?"

"Make like an ice fly," he said, laughing. And in short order, with the help of the two men above, I was able to walk my way up the wall of icicles and into the sun again.

Wind wafts new life to deception

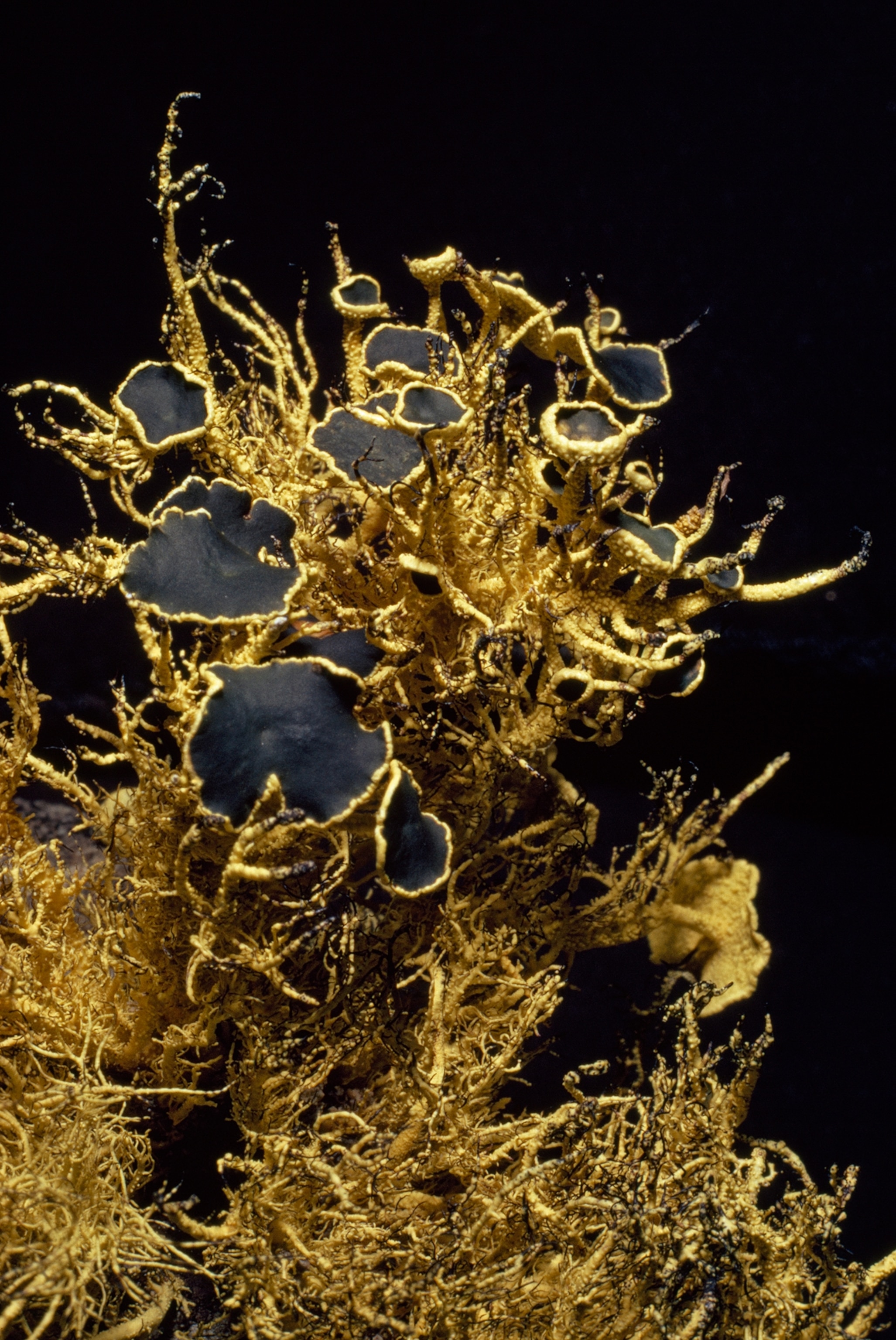

Days that followed added experiences enough for a lifetime. We swam in 100° F. water in a crater lake walled by ice and ash. We dug snow pits in another glacier, and walked the new harbor shoreline formed in the 1970 eruption. Beside steaming fumarole cracks on a beach still almost too hot to touch, moss grew in long green stripes.

"Spores must have come in on the wind since August," Olav said, "for life to have reestablished itself so soon."

Below the surface of the bay, other new life was blooming. Two marine biologists aboard Hero, Stephen Shabica and Michael Richardson of Oregon State University, spent their days in black-rubber wet suits and scuba gear, scanning and sampling the bottom.

"Under about 30 feet, beyond the sunlight, there's not much except cinders," Mike reported. "But above that depth, algae are already growing, and quite a few bottom creatures are feeding on the slime and plants."

One strange 12-legged, foot-wide sea spider that Steve Shabica took from a trawl as we left Deception made worthwhile the entire 14 months he had spent at Palmer as station scientific leader. "It's a Dodecolopoda mawsoni!" he exclaimed. "Only three others have ever been found!"

The Deception Island study completed for the year, Hero returned briefly to Palmer, then sailed north again to return Leonid Govorukha to the Soviet Union's Bellingshausen Station on King George Island.

Pitching in the swell came a bargelike Russian craft to take us ashore. A burly smiling figure in a blue wool cap clambered over Hero's rail, to greet Leonid with a bear hug and a kiss on both cheeks.

Leonid introduced him with a flourish. "Igor Simonov, base leader."

We clung to steel braces as the Russian launch wallowed to shore—and, startled, felt it climb out onto the shingle beach with a grinding clash of gears. We were riding an amphibious rubber-tired truck, which drove us smartly to the station door.

Thirteen Russians, black-garbed and bearded, welcomed us royally. They were out of potatoes, out of fresh fruit, and—worst of all—out of vodka. Their annual relief ship, the Professor Viese, had crossed the Equator that day, southbound. But they heaped a table with the last of their delicacies, mushroom soup and shashlyk (shish kebab). Then they learned that we had brought a surprise of our own.

"This is geologist Alice Brocoum, of New York City," Leonid began the formal introductions. And added quickly, "And this is her husband Stephan, also geologist. They go with Hero to the South Orkney Islands."

"Not before we present a diploma, a certificate," countered Igor Simonov. And at the luncheon's end, the Russians produced a handwritten scroll honoring "the first American woman scientist to visit Soviet Antarctic Station Bellingshausen."

Next door to the Russian base, built in 1968, stands an even newer Chilean station, Presidente Frei. The two outposts provided striking contrasts.

The Russian station abounded in mechanized equipment: two amphibious trucks, a tracked glacier vehicle, several big tractors. Each man had a green plant growing in his room, or a fishbowl flashing with guppies. Pictures of wives and children hung beside beds; portraits of Marx, Lenin, and Engels covered a wall of the dining hall.

The Chileans across the beach, still building, dug gravel and mixed concrete by back and arm power. But their radio room far surpassed Bellingshausen's—or Palmer's. It held five radioteletype printers, high-powered transmitters, and a weather-satellite receiver to provide up-to-the-minute data for the World Weather Watch.

Hopeless haven—after 24 weeks at sea

Hero's Captain Hochban had planned to anchor overnight off Bellingshausen, but the wind was rising, and we had 400 miles of open ocean to cross. By dawn the weather had indeed changed for the worse. Hero was rolling and plunging; long graybeard waves marched northeast across a gunmetal sea. They lifted our stern and swung our bow as they hissed past in spumes of white foam.

Abeam to the north, dark and ominous through the scudding overcast, rose a dim serration of forbidding cliffs and peaks. Elephant Island, Captain Hochban said.

To that black outcrop, in April 1916, British explorer Ernest Shackleton brought his castaway party of 28 men, "huddled in the deeply laden, spray-swept boats, frostbitten and half frozen." They had ridden the pack ice and dragged and sailed their three small boats for 24 weeks through the frozen waste of the Weddell Sea, after the "unsinkable" Endurance had been beset and finally crushed. When they landed through wild surf on Elephant Island, it was the first land they had set foot upon in 497 days.

"South Georgia was over 800 miles away," Shackleton wrote. But "... there was no chance at all of any search being made for us on Elephant Island."

With five of his men, he set forth in a 22 1/2-foot open boat. "We fought the seas and the winds and at the same time had a daily struggle to keep ourselves alive." But they made it.

Thrown ashore on the opposite side of South Georgia from its Norwegian whaling stations, Shackleton and two of his ragged, emaciated men crossed an all but impassable mountain range to reach safety and organize rescue for the others. His feat stands as one of the greatest epics of seamanship and will to survive in history.

Between Elephant Island and the South Orkneys, Hero growled gamely on. We passed ever-increasing flotillas of icebergs drifting north out of the Weddell Sea. One berg stretched seven miles; another, appearing by night out of a whitish iceblink, ran on for 16 miles. Each rose 80 to 100 feet out of the sea, which meant their total thickness was close to 800 feet.

Nathaniel Palmer and British sealer George Powell discovered and charted the South Orkneys late in 1821. Then, as now, the islands were the breeding ground of millions of chinstrap penguins and other Antarctic birds. Bleak and totally for bidding, the South Orkneys interest geologists today simply by being where they are.

Steve and Alice Brocoum and Mark Barsdell, a young Australian, made up a field team led by Dr. Ian Dalziel of the Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory of Columbia University. Athletic and dedicated, with a Scottish burr in his voice, Ian was pursuing the third year of a study of the ancient land connection between South America and Antarctica. He sought evidence written in rock of what happened when those continents drifted apart in the breakup of the ancient proto-continent geologists call Gondwanaland.

"There's little doubt the South Orkneys are displaced fragments of the original Andean mountain chain," Ian said. "As the South Atlantic opened, and South America and Antarctica moved away from Africa, the land connection across what is now the Drake Passage apparently broke and bent in a great eastward curve. The Orkneys are remnants of that land bridge."

Day after day we scrambled ashore from Hero's bouncing rubber boats, and Ian and his nimble rock hoppers showed me evidence of that massive geologic displacement. Along the crags and cliff faces of Laurie Island, they pointed out tiny ripples in ancient sediment beds that told them that the layers had been shoved and folded upside down.

On many a rocky beach we were outnumbered by glossy dark-brown seals basking in the sun. These were unlike any seals I had seen near Palmer Station. They had ears. They stood up on their flippers and broad tails, barked ferociously at us, then galloped away like bears on the run.

"Those are fur seals," Ian told me. "We saw a few on Elephant Island last year, and others in the Shetlands."

The reappearance of this once almost extinct mammal is heartening. Guidelines for its protection have been developed by signers of the Antarctic Treaty.

Repast at Antarctica's oldest station

At Laurie Island, when Hero anchored in Scotia Bay, Ian wore a bit of a grin as we went ashore. On a low isthmus stood the ruin of an old stone hut. Atop its door frame a weathered signboard read, "Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, 1903-1904."

Next to the hut stretched the blue and orange buildings of Argentina's Orcadas Station, established the year the Scots left. Orcadas thus ranks as the oldest continuously inhabited outpost in the Antarctic.

Its all-naval complement welcomed Hero with a startling repast: Hearts-of-palm salad ("from our palm grove across the glacier"), marinated artichokes, Argentine tenderloin of beef, and flaming crepes suzette!

An equally friendly crew of young Britons greeted us at Signy Island, 25 miles west biologists, divers, mechanics, radiomen of a British Antarctic Survey base. Anchored off their two-story, fiber-glass station lay a red and-white vessel, the spanking new royal research ship Bransfield. Commissioned the last day of 1970 at Leith, Scotland, the Bransfield sailed at once for the Weddell Sea.

Aboard was BAS Director Sir Vivian Fuchs, leader of the British Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1957-58, first to cross Antarctica by surface travel. Ruddy and still youthful under bushy brows and silver-gray hair, "Bunny" Fuchs is one of the world's most experienced Antarctic hands.

When our talk turned to the subject of tomorrow's Antarctic stations and research projects, Sir Vivian expressed views surprisingly similar to those Dr. Quam of USARP had voiced. Fifteen years after the start of the huge IGY effort in Antarctica, they both saw one era ending and another beginning.

"Has it been worth it?" I asked them.

Dr. Quam: "Few if any other international efforts in history have produced as much basic knowledge of the world we live in."

Sir Vivian: "I agree. The Antarctic program is—and, to my mind, rightly so—one of Britain's largest research efforts."

Both men predicted that the patient unraveling of Antarctic mysteries will go on.

Stations will remain small and inevitably isolated. But U. S. use of large ski-equipped aircraft, able to land research parties in remote regions for short periods of intensive work, has shown that scientists no longer have to remain in Antarctica for one, two, even three years at a time.

The United States will continue to keep men at the very bottom of the world, Dr. Quam said. Construction of a new South Pole station, sheltered under a geodesic dome, will begin in the 1971-72 austral summer.

For such small inland bases, Navy station keeping for civilian scientists is on its way out.

"Where a small group must live close together and totally isolated for at least part of a year, as at the Pole, dividing that group between Navy support personnel and civilians no longer makes sense," Dr. Quam went on. "I foresee our smaller bases, particularly, becoming all civilian, like the British."

The U. S. will use women. Britain will not.

“We simply aren't equipped to have both men and women at our bases today," Sir Vivian said flatly.

In the past two years, U. S. women scientists have worked at McMurdo, Byrd, and in the Cape Crozier area. Geologist Alice Brocoum was the first woman to sail in the Antarctic with Hero. There will be others.

Further in the future lies possible economic development of earth's last great landmass. Tourist ships already sail regularly along the peninsula, and occasionally to McMurdo. Inevitably there will be more.

"The treaty nations must agree on ways to receive and safeguard visitors without disrupting scientific work," Dr. Quam said.

Minerals and other resources wait there too, for men to find—and find how to get them out.

"Almost certainly there is oil," Ian Dalziel told me. "The east side of the peninsula is similar in geologic structure to parts of southern Argentina, where oil is already known to exist." Sir Vivian agreed.

Someday the virtually limitless shrimp-like krill, a vital link in the food chain of Antarctic waters, may provide a huge new food resource for a hungry world. Reduced to a protein concentrate, cheap and palatable, planktonic life from the southern ocean could feed millions of people, say both British and American marine biologists.

There may be other bonanzas as well, but they, too, lie far in the future. Antarctica's real wealth is already being mined, however—new basic knowledge of the earth, its weather and atmospheric circulation, the forces that impinge on it from space.

Homebound race against winter

At Signy Island, Ian and his party went ashore with tents and field gear to camp for nearly a month amid the geologic record of continental drift. I, too, transferred from Hero. I was to sail with the Bransfield back to Punta Arenas.

From the Bransfield's broad helicopter deck, at four o'clock one gray gusty morning, I watched Hero swing from her anchorage and head out into a scudding, rolling, forbidding ocean. The little USARP ship was bound back to Palmer Station for the last visit of the waning summer. Gales and gathering pack ice would soon usher in the winter night along the peninsula. Bucking head seas and winds, Hero would have to hurry.

I had been aboard her for 50 days. She was cramped, sea-tossed, tired, and far from home. As I watched her go, I had the same thought as when I first saw her two months before. Uncle Sam's little wooden ship of the Antarctic is most aptly named.