Caught on the RattleCam: a most unexpected snake behavior

For a long time, scientists didn’t think snakes needed each other. New research proves that wrong.

Picture an animal that huddles up with others when stressed, babysits its young, hangs out around relatives, and gathers in big groups every year.

Did you imagine a rattlesnake?

For a long time, scientists didn’t think snakes could fit this description.

“There were two big myths out there,” said Noam Miller, who studies animal social cognition at Wilfrid Laurier University. One is that snakes largely just operated on reflex. The other is that snakes don’t gather in general, since people tend to only come across one snake at a time. “So there was this idea that they were just not social at all.”

But over the past few years, researchers like Miller have found in laboratory and field experiments that numerous snake species — from rattlesnakes to pythons — have surprisingly active social lives, suggesting that researchers have long underestimated an extremely misunderstood — and threatened — group of animals.

Why snakes are hard to study

Research has revealed that crocodiles and lizards have dynamic social lives, but snakes received little such attention until recently. Part of the trouble with studying snake social behavior is that — even more so than other reptiles — they’re quite secretive. “Most of the time you can’t even see them — they hide somewhere,” said Vladimir Dinets, a specialist in reptile behavior at Rutgers University.

Snakes also live very different lives from most mammals and birds, which often live their lives in the open, making them easier to study. Rather than extravagant displays or calls, Dinets noted, snakes spend most of their time hiding and depend largely on their sense of smell. A snake’s world consists mainly of chemical trails and signals, making its perspective closed off to more visual animals like us. “For us, it’s very difficult to study.”

That’s one reason that researchers interested in reptile social behavior have tended to pay attention to one particular serpent, Miller said: the red-sided garter snake. This species is found from the American Midwest to Manitoba, Canada, give live birth rather than laying eggs, and hibernate in massive groups over winter. When they emerge in spring, they form mating balls, thousands of snakes strong. For Morgan Skinner, a student in Miller’s lab, garter snakes seemed like a natural species to observe more closely: “They were the group we already knew had some kinds of social behavior.”

The scientists began with experiments to see how eastern garter snakes learn, only to run into a problem: Snakes are difficult to motivate. “They more or less didn't care about many of the tasks we were giving them,” Miller said.

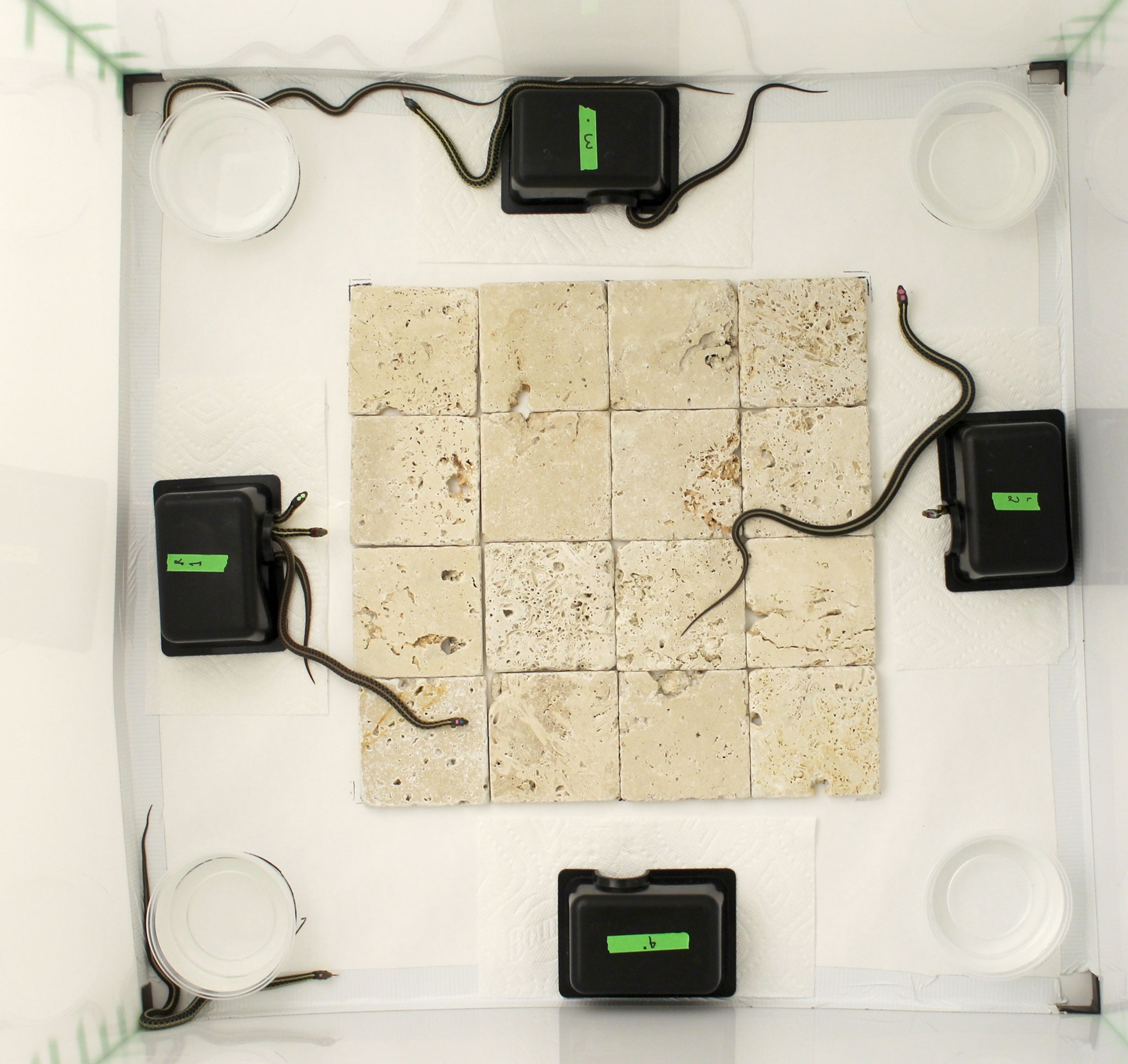

Instead, he and Skinner decided to just watch the snakes to see what they did. They constructed an open arena with a bunch of different shelters and deposited 40 young Eastern garter snakes — each individually marked — inside. By recording the snakes and tracking their movements in the arena, they collected data about which snakes congregated with each other. In their published results, they found that the young snakes not only preferred to gang up with each other — snakes tended to stay longer in shelters that were already well-occupied, and coordinate times when they went out exploring. They also seemed to massively prefer associating with specific other individuals, “what we colloquially refer to as ‘friends,’” Miller says.

“Even though people knew that garter snakes were social to the extent that any snake is social,” Miller says, “the sophistication of what was going on socially was not, I think, widely suspected.”

Garter snakes aren’t the only species that prefer company. Many North American rattlesnake species — including western diamondbacks, black-tails and prairie rattlers — also give live birth and den communally over the winter, said Emily Taylor, a rattlesnake specialist at California Polytechnic State University. But while advances in radio-tracking technology allowed researchers to begin mapping rattler movements in the 1980s, the depth of their social behavior is now coming into focus. A 2004 study of captive timber rattlers found that the female snakes recognized — and preferred to associate with — their sisters, while a 2011 study on blacktail rattlesnakes found that solo rattlesnake mothers actively looked after their new hatchlings for several days, including driving off predators.

Caught on the RattleCam

Some of the most exciting discoveries have come from “Project RattleCam,” a donation-funded livestream Taylor and her colleagues set up for a massive rookery of prairie rattlesnakes in Colorado, where dozens of pregnant females gather to give birth before hunkering down together for the winter. While rattlesnakes — like most other snakes — are secretive, this annual, months-long gathering has provided an opportunity to see “wild social behaviors that we had no idea they were doing,” Taylor said.

One of those unexpected activities is babysitting. “There's hundreds of babies in the summer, and we see that the babies tend to curl up on or with an adult,” Taylor said. “But that the adult isn't always the mom.” Since the pregnant females give birth at different times, there are always adults around to guard newborn rattlers against birds and other predators. The young often stick around the rookery over the winter hibernation and into the following spring.

These dens aren’t just alliances of convenience. While snakes do seemingly spend a good chunk of the year alone, the den seems to be the locus of rattlesnake society, Taylor said. In 2023, a team of researchers demonstrated that snakes were less stressed by disturbances if they had another rattler to huddle with. This year, Taylor said, they’ve completed a forthcoming study on the Colorado den, using the recorded livestream to determine which snakes spent the most time together.

“We saw very, very strong signatures that that certain females seem to prefer to hang out together,” Taylor said, with pregnant females generally preferring each other’s individual company. (Males — who came to the den to wrestle rivals, mate and hibernate — seemed much less choosy.)

The camera even caught what might be a strange sort of communication, Taylor said: Rattlers who approached one another often twitched their heads at each other back in forth in rapid, noticeable patterns — gestures whose meanings the team hopes one day to decode.

Python parties

Both rattlesnakes and garters are unusual as snakes go, however: they inhabit more temperate environments, hibernate communally, and give live birth. In 2020, Skinner wondered how a snake with a very different ecology and no reported social behavior would fare under close observation. Skinner and Miller chose Ball Pythons, a small, seemingly solitary African python popular in the pet trade.

As they had with garter snakes, they put five different groups of young pythons in the arena with enough plastic enclosures for each snake, and left them there for 10 days with a camera running. To the lab’s surprise, all six snakes quickly squeezed together in the same shelter, spending over 60 percent of their time together. When the team removed that shelter to make sure there wasn’t something unusually appealing about it, the pythons picked another. Skinner repeatedly shuffled the snakes between shelters, placed them all out in the open, and removed favored hides. Again and again, the young pythons congregated together.

Surprisingly, the ball pythons were more social — and less cliquey — than the eastern garters had been, Miller said. “The thing they tend to do the most is all cram into the same shelter. And because of that, we actually can’t even identify if they have friends or not.”

When the team looked at the pythons’ brains after a social experience, Miller said, they found that certain brain areas lit up — the exact same ones found in an area called the “social decision making network,” in bird and mammalian — including human — brains. That suggests that when it comes to gathering in groups, snakes are using a cognitive toolkit similar to that of other animals.

While their social behavior may be simpler than what is seen in many birds and mammals, Miller said, it’s the same basic brain process. “All of the things that they do are very much things that we also do,” he says. “We've just overlaid a bunch of other complications on top of them.”

Miller’s lab has already run similar experiments on hognose snakes, a shovel-nosed, supposedly anti-social toad-eater found in North America, and corn snakes — and while they have yet to publish the results of these investigations, the team found similar results, Miller says.

These sorts of observations are likely just the beginning when it comes to studying snake social behavior, Dinets says. There are many observations of snake socialization in the wild that haven’t been followed up on, in part because study would be too difficult. Yellow bellied sea snakes, for example, gather in occasional huge groups before vanishing into the vastness of the ocean, while some species seem, by contrast, territorial around potential food areas— which is a different form of complex social behavior.

A laboratory environment is inherently artificial, so there is always the possibility that the snakes act differently in experiments than they would in the wild. But based on Dinets’ own observations of crocodilian social behavior, he says it’s reasonable to assume that many species are actually less sociable in captivity than they are in nature. In other words, lab experiments probably capture a lower level of social behavior than the snakes display in their natural habitats.

“The idea that reptiles are not social is basically just conjecture,” Dinets said. “Every time people start looking at reptiles, they start finding it. Pretty much all of them will prove to be more social than we expect.”