Snapping Shrimp 'Dinner Bell' May Tell Gray Whales When to Eat

The racket created by snapping shrimp could be one of the factors drawing eastern Pacific gray whales to the waters off the Oregon coast.

Do you ever wish you could just snap your fingers and have dinner ready? Well, that dream is kind of a reality for one species of whale.

Snapping shrimp are the noisiest creatures in the ocean. They make the sound that gives them their name by rapidly closing and opening the larger of their two asymmetrical claws, at a speedy 60 miles per hour. This motion forms giant air bubbles that, when popped, generate enough energy to stun or kill nearby prey.

Together, this crustacean ruckus is like a very loud rainstorm. If a large enough number of shrimp is congregated, the snapping can even sound like a passenger jet zooming overhead.

For the first time, scientists from Oregon State University have captured this snapping sound in the rocky reefs off the cool coast of Oregon. And they're saying this ultra-loud clacking might be acting as a sort of "dinner bell" for nearby eastern Pacific gray whales, letting them know when to come and chow down on their next meal. They presented their research February 13 at the annual Ocean Sciences meeting.

Finger Clickin' Good

When the scientists started their study, they were not looking for shrimp. Rather, they were continuing research to evaluate what effects underwater background noise had on the hormones and bodies of gray whales. Cetaceans, like whales, dolphins, and porpoises, are sensitive to acoustics, so different marine soundscapes can have different effects on the mammals. (Read: "The Earth is Humming—Here's What It Means")

In 2016, the researchers began gathering soundscape data by placing a drifting hydrophone—a microphone that records underwater—in the cold, shallow waters off the coast of Oregon. Snapping shrimp are known to inhabit warm, subtropical waters, but they haven't been found in the Pacific Northwest until now.

"The target of the research we were doing was not related to snapping shrimp at all," says Joe Haxel, a marine acoustics researcher at Oregon State. "We were really surprised when we went into these areas. We thought it was going to be really quiet and found this loud din of snapping shrimp."

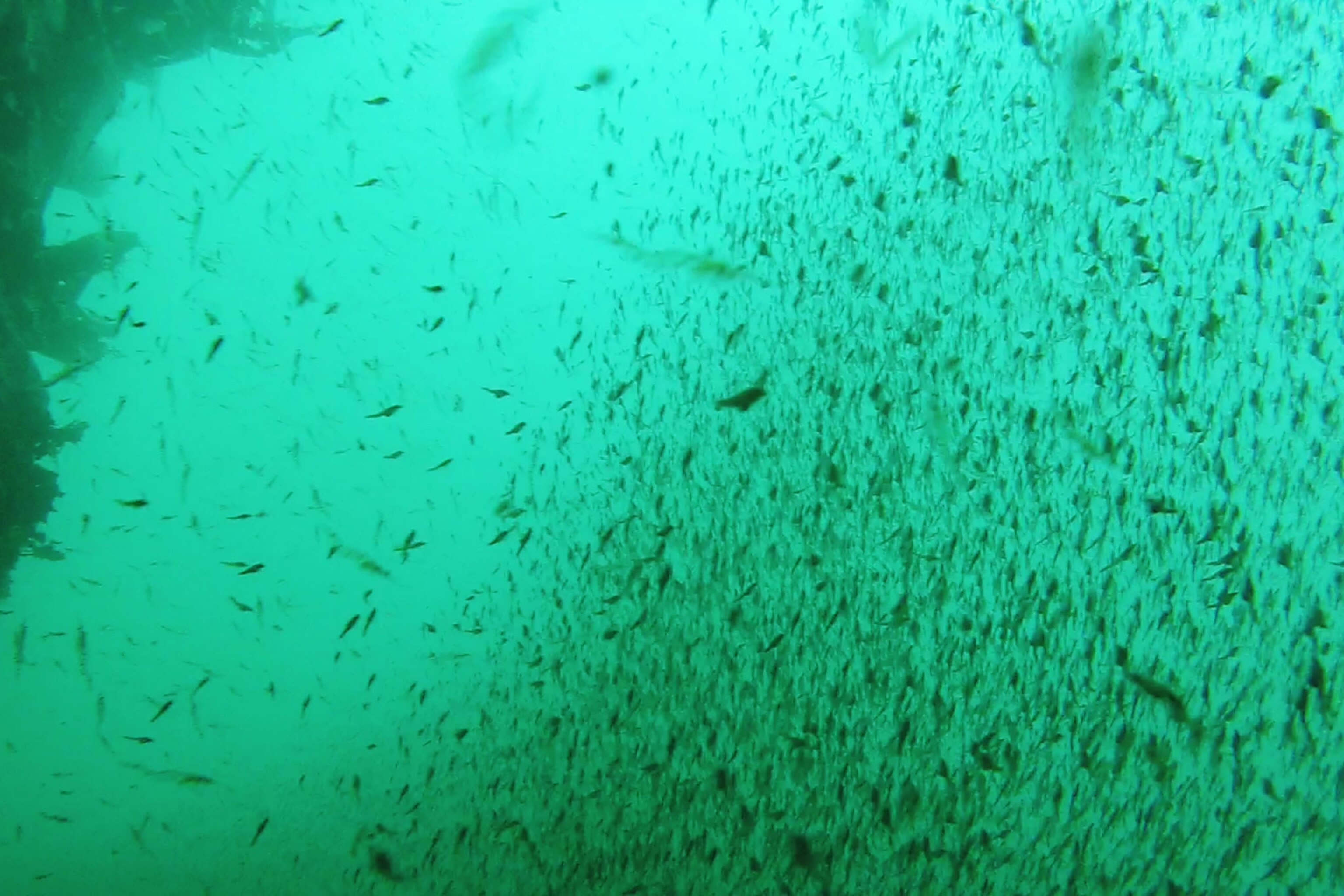

Though they haven't been able to spot the shrimp yet, the researchers know the crustaceans are hiding in the cracks of coastal rocky reefs near kelp beds. At the same time these shrimp were snapping, the researchers observed eastern Pacific gray whales swimming into the area to feed on mysids, small crustaceans that live in the same kelp habitat as the shrimp. (Related: "Watch Never-Before-Seen Whale Behavior")

The researchers studied the whales, operating their boat around them and flying a drone over them to try to see if they were actually feeding or just foraging for food. They found that the whales were feasting on the mysids. The team hypothesized that the sound from the shrimp could be a factor drawing the whales to the area. The snaps of the shrimp could effectively act like a "dinner bell" for the whales, letting them know when to come and get their next meal.

Gray whales feed at all hours, including at night. The acoustically sensitive animals can't always rely on sight, so it's possible they listen to the sounds of snapping shrimp to know when to feed. But, the researchers caution there could be other factors driving the whales to feed near the reefs. Certain scents may also draw the whales in. (Related: "Watch the World's Biggest Animal Lunge for Its Dinner")

"The snapping shrimp are basically making a potential cue," Haxel says. "This could be one of the ways that [the whales] do find food, one of many."

Listening In

The research is part of a larger effort to try to understand the acoustic environment surrounding the coastal waters of the Pacific Northwest. Snapping shrimp—loud as they may be—are only one species in this diverse habitat, which also includes sea lions, harbor seals, and other marine species.

It's unclear how long the shrimp have been there, but Haxel says it's unlikely they've gone unnoticed for very long.

"I can't imagine. I would have thought someone would have heard it by now," Haxel says.

This spring and summer, the research team will set up traps to try to catch some of the shrimp. They want to figure out what specific species is making all the noise, and how long they've been in the area for.

"We're just starting to peel back the layers on this picture," Haxel says.