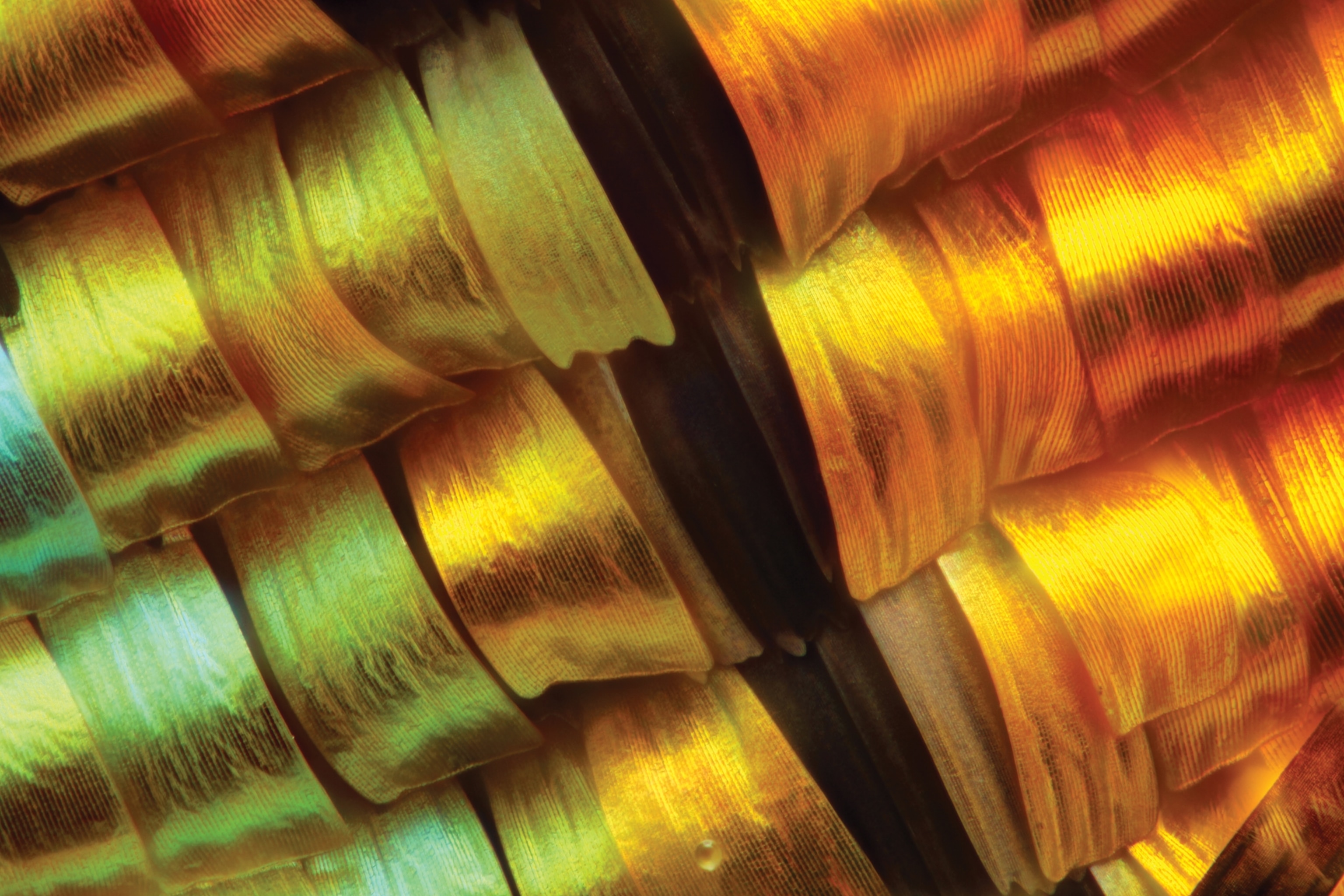

These stunning insect close-ups reveal dazzling bug complexity

Hard yet flexible, chitin builds insects’ exoskeletons, wings, and scales.

Arthropods are the most diverse group in the animal kingdom. Among them, the evolutionary record holders are the insects, thanks to their ability to adapt to many different ecosystems both in water and on land. The versatility of arthropods is due in large part to chitin, a substance that forms their hard outer covering as well as their wings and other flexible parts. Like cellulose, the building block of plant cell walls, chitin is made of glucose molecules, but it also contains nitrogen, producing a firm structure.

Chitin is the main component of the arthropod’s exoskeleton, the first rigid form to evolve in multicellular organisms: arthropods made chitin as early as 550 million years ago. Secreted by the epidermis, or skin-like, soft outer layer, chitin combines with other compounds to form the waxy, water-repellant cuticle.

A remarkably hard yet flexible material, chitin strengthens insect mandibles to cut through rock and metal, and provides elasticity between the stiff body segments, enabling speed and agility. The tiny, delicate scales covering insects such as butterflies also contain chitin. It’s integral to the thin tracheal tubes that make up their respiratory system and the hairs that collect pollen.

It seems chitin can do almost anything—except allow an exoskeleton to expand. So, in order to grow, arthropods must molt. Every so often they have no choice but to temporarily shed their protective chitinous covering in exchange for a little bit of room to grow.