Scientists reveal the secret of toads that can turn neon yellow

The color change, driven by hormones, seems aimed at preventing males from accidentally mating with each other.

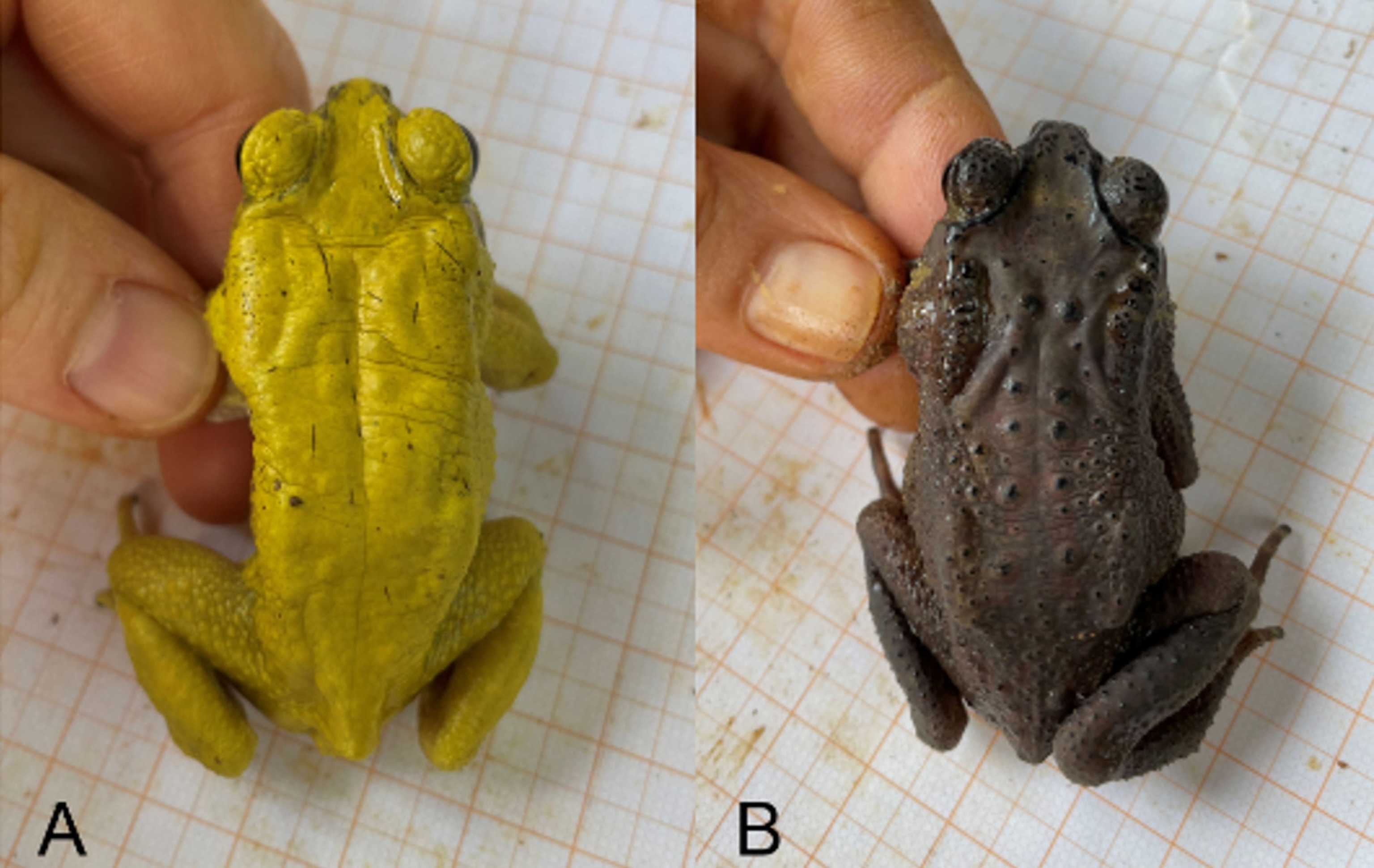

As the first monsoon rains in India and southeast Asia begin to swell each year, one type of toad experiences an almost literal glow up. A temporary, hormone-induced wardrobe change transforms male Asian common toads (Duttaphrynus melanostictus) from chocolate pudding brown to lemon yellow in a matter of minutes.

While the females’ skin remains brown, males undergo a color palette makeover to get ready for a lightning round of speed dating. Scientists have long known that the color change coincided with a frenzied, annual two-day breeding event, but they only recently confirmed the specific role it plays.

To investigate, researchers from Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna 3D printed toads — some brown, some yellow — and placed them amid real toads gathering to mate. They found that the male toads largely ignored the yellow models, but frequently attempted to mate with the brown ones, which matched the color they would expect of females. The researchers tried varying other factors, such as the model toads’ weight, size, and color saturation, but nothing else seemed to affect which models most attracted the male toads.

Scientists say this strongly suggests the toads naturally color-code themselves to prevent any cases of mistaken identity. While males of other species often display brilliant colors to attract females, these toads seem to turn traffic light-yellow to send a signal that repels other males.

“In explosive breeding species, mispairings are common,” said Susanne Stückler, a research associate at Schönbrunn Zoo who led the study. Since the breeding period is so brief, toads must find mates very quickly. Competition is fierce, especially because female toads are scarce.

In their fervor, Stückler says males may attempt to mate with other males, the wrong species of toad, fish, or even inanimate objects. “This suggests that identifying the correct mating partner can be difficult in these dense and stressful conditions,” Stückler said. “Coloration appears to be one evolutionary solution to this problem.”

This type of research could change how scientists think about the evolution of color across the animal tree of life, says Rayna Bell, the curator of herpetology at the California Academy of Sciences who was not involved in the study.

“This isn’t the first study to show this kind of signaling in frogs, but what I think is really cool about it is that it could alter how we interpret color signals even in those groups we think we already understand, including more charismatic examples like birds or butterflies,” Bell said. “Paying attention to less-studied animals could offer new ideas that make us reevaluate what we thought we knew about signaling processes across the board.”

Unlike other animals such as octopuses and chameleons, which can change color within seconds, it takes about 10 minutes for the male toads to turn yellow. That’s because it’s driven by hormones, rather than skin cells that are directly controlled by nerves. The yellow hue lasts up to 2 days before fading back to brown.

How do they transform themselves? Beneath the toads’ skin, there are layers of specialized cells called chromatophores. Some contain dark pigments, others carry yellow and red ones, and a third type reflects light like tiny mirrors. Stress hormones like adrenaline seem to trigger the toads’ bodies to rearrange pigments and tilt those reflective plates.

The color change may sound like a rare instance of cooperation in the wild. But the toads are still very much in competition.

“They fight, kick, and try to displace other males” who are already attempting to mate, Stückler said. “Sometimes, several males try to [simultaneously mate with] the same female, forming ‘mating balls,’ which can even lead to female drowning.”

Climate change may further strain an already hectic and precisely timed event. Though monsoon season lasts for a few months, Asian common toads, along with many other amphibians, breed during a specific one- to two-day period at the beginning. That’s because the babies need to hatch and develop as much as possible prior to winter for the best chance of survival. When the rains arrive and begin to puddle up, the toads quickly mate and tadpoles have time to grow into baby frogs before their habitat dries up again.

But shifting weather patterns are scrambling both the timing and intensity of monsoon season, which could disrupt many species’ already narrow window of opportunity. If toads lay eggs during a short rain spell before a long duration of sunny days, “all the eggs would desiccate and reduce the population in the coming years,” says K. V. Gururaja, an amphibian expert at Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology in India, who co-authored the study. The survival of explosive breeding species like the Asian common toad may hinge on their ability to go with the monsoon’s shifting flow.