Inside the Black Market Hummingbird Love Charm Trade

There’s a witch in San Diego who casts spells to “trap a man” and “dominate him” so “he’ll always come back.” She has a shop on San Ysidro Boulevard, one mile from the busiest Mexico border crossing in the United States, near a pawnshop, a liquor store, a furniture market, and the Smokenjoy Hookah Lounge, where DJ music thumps on Friday nights.

But you don’t need to go to her shop for magic—you can join the tens of thousands watching her on YouTube. Like a wicked Martha Stewart creating potions instead of potpourri, she provides step-by-step instructions for her spells.

“This is the honey jar,” she tells viewers while introducing the ingredients on her workbench: photographs of two would-be lovers, a piece of paper with their names written on it three times, a small glass jar—and a dead hummingbird. She rolls the tiny animal inside the photographs and wraps the cigar-shaped bundle with hot-pink yarn nearly the same shade as her long, fake fingernails.

Showing only her arms and lower body on camera, she shields her identity as she swaddles the package in a sarcophagus of tacky flypaper, dips it in cinnamon spice, squeezes it into the jar, and spritzes it with perfumes and oils—pheromones—“so he’ll stay sexually attracted.” Restless balm “so he’ll be like, ‘Oh my God, I need to call her.’” Sleep oil “so he’ll be like a zombie.” Attraction oil “so he’ll be like, ‘Goddamn, you so beautiful, you so fine.’” Dominating oil “so you dominate his thoughts.”

Finally she fills the jar with a thick pour of golden honey and tops it with a sprinkle of rose petals. “I love this,” she says. “I’m already getting a really good vibe.”

As an entrepreneurial saleswoman, she tells viewers that any hard-to-find ingredients used in her creations are available for customers. For example, on her website a dead hummingbird—in life a feisty little iridescent green creature with rust-colored tail feathers—is $50. Buying a ready-made honey jar is another option. In an email she quoted me $500.

Had I typed in my credit card number, I’d have been committing a felony. Multiple federal and international wildlife laws protect hummingbirds and most other feathered animals from being bought and sold. Even possessing undocumented birds is a serious crime. Last May a California man on a flight from Vietnam got caught at Los Angeles International Airport with nearly a hundred “good luck” songbirds in his suitcase. He was sentenced to six months' home detention followed by a year in prison.

YouTube voodoo starring dead hummingbirds isn’t just some weird internet thing—it’s a peek inside the dark world of a mysterious international trade that may pose a serious threat to a group of animals already facing declines from habitat loss and climate change.

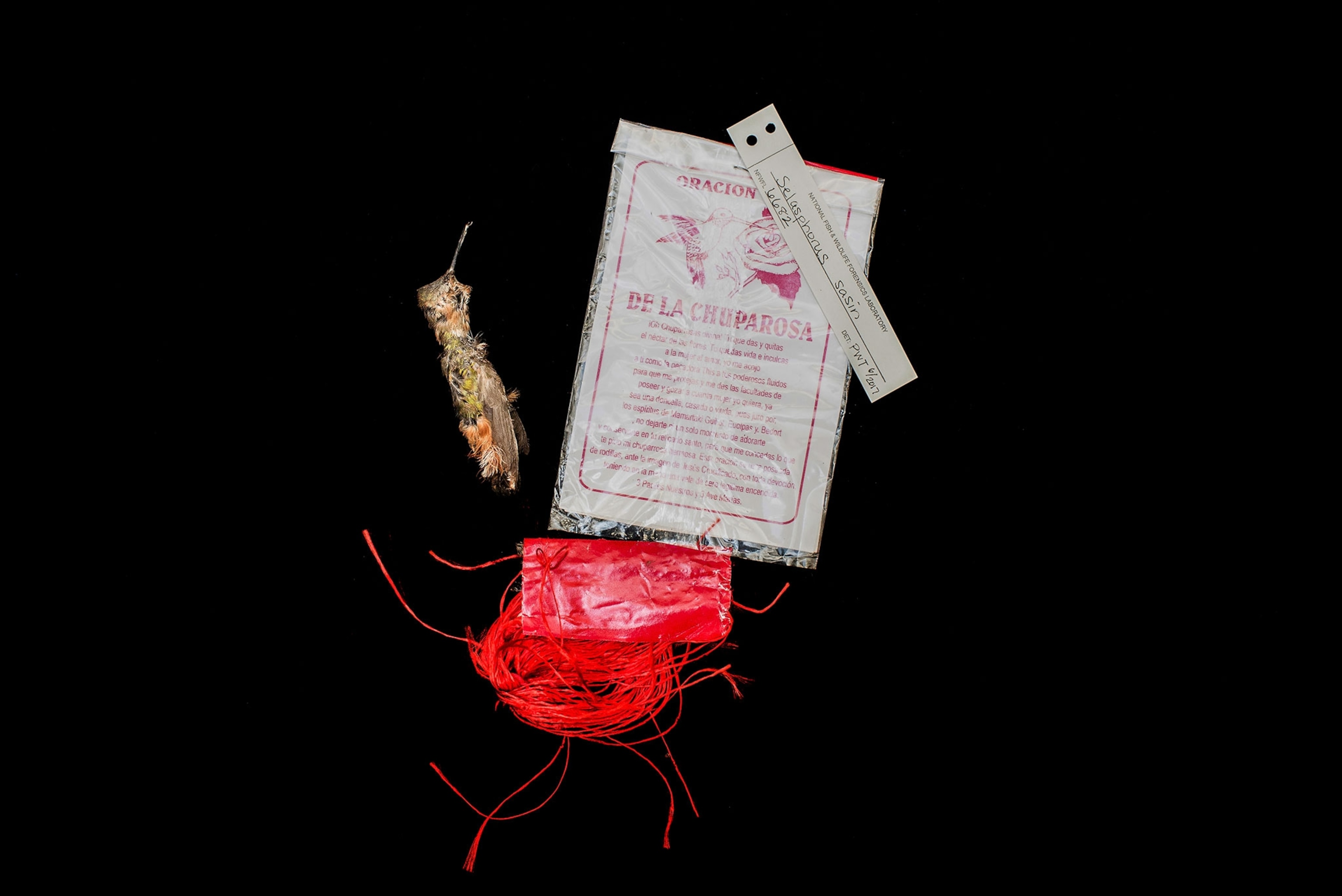

Some Mexicans believe hummingbirds have supernatural powers. Beyond the internet, merchants sell them from behind counters at spiritual shops called botanicas, filled with herbs, incense, candles, oils, and scythe-wielding statues of Santa Muerte, the goddess of death. Mystics call the hummingbird la chuparosa, a token akin to a lucky rabbit’s foot for good fortune in love. Chuparosas are often sold wrapped in red paper and satin tassels with an accompanying love prayer: “Divine hummingbird ... with your holy power I ask that you enrich my life and love so that my lover will want only me.”

LOVE CONNECTION

The underground market for hummingbirds is so secretive that U.S. government officials didn’t even know it existed until about 10 years ago when agents with the Fish and Wildlife Service intercepted a postal package inbound from Mexico containing dozens of lifeless, jewel-colored birds.

“We were like … hummingbirds? What do people do with a commercial quantity of dead hummingbirds?” recounted Special Agent James Markley, who has led investigations into the hummingbird trade. He soon learned about the love connection. “Women trying to attract a man, widowers hoping to remarry, men carrying them as a way to keep their mistresses and wives from meeting each other, a wife trying to prevent her husband from straying and looking at other women,” he said. "We’ve heard all sorts of stories.”

Hummingbirds have played important roles in Latin American cultures, religions, and mythology. The Inca used hummingbird feathers in their fine garments, ritual sacrifices, and even architecture. On the Isla del Sol in Lake Titicaca, south of Cusco, in Peru, an entrance to an important Inca shrine was covered in hummingbird feathers.

In Aztec mythology the hummingbird represents the powerful sun god Huitzilopochtli, conceived by his mother after she clutched to her breasts a ball of hummingbird feathers—the soul of a warrior—that fell from the sky. Mexican elders say Huitzilopochtli guided the Aztec’s long migration to the Valley of Mexico, and thus the hummingbird is the symbol of strength in life’s struggle to elevate consciousness—to follow your dreams.

These days, in addition to being powerful love tokens, hummingbirds are considered messengers from the heavens and “road openers” for travelers. Markley recently met a former narcotics detective who encountered dead hummingbirds in shrines used by the drug cartels to pray to the patron saints for safe passage, good luck, and protection from the police.

Federal agents posing as customers usually find hummingbirds for sale at botanicas in little plastic bags containing a satin-wrapped bird and a love prayer. Average price: $45. Texas has been a hot spot. In 2013 a man named Carlos Delgado Rodríguez, who owned a botanica in Dallas, offered the undercover Markley a wholesale discount: 35 chuparosas for $770.

In the months that followed, Delgado continued making deals, selling Markley more than a hundred hummingbirds. The agency was able to identify at least 60 of them representing 10 different species, including several in steep decline.

In May 2014, after the last day Delgado met Markley to swap bird cadavers for cash, he was arrested, according to court documents. A five-count indictment charged him with violating the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which regulates the global wildlife trade, as well as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the U.S. smuggling law known as the Lacey Act, and Texas state law. The judge in the case sentenced him to four years probation and $5,000 in fines.

That punishment was light, Markley said, but the verdict was a victory because it had shut down a smuggler. “Think about it,” he said. “If these were elephants or bald eagles, and we bought that many from one person. It’s crazy.”

A key component of the case was the analysis of the birds at the Fish and Wildlife Service’s forensic lab in Ashland, Oregon, where experts in pathology, morphology, and chemistry examine crime-scene evidence using high-powered microscopes and scientific instruments that can even distinguish an endangered tree from a splinter of wood.

The lab’s Sherlock Holmes of bird crime is Pepper Trail, who has spent 20 years poring over feathers and bird carcasses to help ID avian victims in wildlife crimes. Trail, a nature lover and a poet with a furrowed brow and small eyeglasses that sit low on the bridge of his nose, is the first to admit that the job can be incredibly depressing.

“Birders have life lists,” he said, when we first spoke, on the phone. He was referring to the way many birders tally the number of species they’ve seen in their lifetimes. “I also have a death list of all the bird species I’ve identified in casework. It’s over 775 species from all parts of the world—everything from penguins and cassowaries to hummingbirds. You’re always learning new things.”

Cracking the case of the chuparosa has become especially important to him. “Hummingbirds are powerful animals,” Trail said. “We respond to their vitality, their pugnaciousness, and their beauty. There’s nobody who doesn’t love hummingbirds. To find that there was this whole exploitation going on that was completely unknown—to me it seems particularly sad.”

No one knows the exact toll smuggling is having on wild hummingbird populations, but some experts are concerned because the demand for love charms appears to be significant and possibly growing.

In 2009 researchers surveying Mexico City’s Sonora “witchcraft” market documented more than 650 dead hummingbirds for sale. Since then federal agents have bought chuparosas with “made in Mexico” stickers—a sign that there’s a commercial market. “Maybe there’s a factory, or at least a good-size shop, making them,” Markley said, adding that they’re “all being processed somewhere.”

There are still many unanswered questions: How big is the trade? Where are the birds coming from? How are they being captured and killed? Are there a few major traffickers, or is the trade decentralized? How many buyers have a sincere belief in love magic or want the birds as novelties?

“Many of the answers lie in Mexico,” Trail told me, “but Mexico is not part of our jurisdiction. It will be interesting to see what you find.” He paused. “Be careful down there.”

GEMS OF GLOWING FIRE

Naturalists have long been in awe of hummingbirds. In the 1800s John James Audubon rhapsodized about some of the “fairy-like” birds he’d chronicled while painting North America’s birds. Writing to a friend, he described the ruff-necked hummingbird as a “breathing gem … of glowing fire, stretching out its gorgeous ruff, as if to emulate the sun itself in splendor.”

Hummingbird colors sparkle, from the glimmering purple crown and iridescent yellow-green throat of the male magnificent hummingbird to the brilliantly scarlet collar of the male ruby-throated hummingbird. They’re famously adept fliers, capable of hovering up, down, forward, backward, sideways, even upside down.

As a group, some 340 species—from as small as a bee to as large as a cardinal—are named for the high-pitched sound of their wings, whirring at up to 80 beats a second. With the fastest metabolism of any animal in nature, hummingbirds hardly ever stop eating, except when they’re sleeping, which they can do only because of their astonishing ability to dial down their inner thermostats and enter a state of torpor, like astronauts deep-sleeping on interstellar voyages in sci-fi movies.

Each hummingbird species is defined largely by its adaptation for drawing sweet nectar from the types of plants it pollinates. At the extreme end of this spectrum, the sword-billed hummingbird’s saber-like black bill is longer than its body. The bird’s beak evolved to gather nectar from flowers with long tubular corollas, including a passionflower that is deeply reliant on the avian rapier for pollination. The sickle-billed hummingbird has a dramatically hooked bill for sucking sweet sustenance from a heliconia blossom while perched on the flower. Found only in Cuba, the itty-bitty bee hummingbird, the world’s smallest bird, weighing less than a dime, is adapted to drink nectar from flowers too small for any other hummer. But since flowers can’t provide all the fuel required to keep the bird aloft, it’s also deft at snatching mosquitoes mid-air.

Hummingbirds may look dainty, but if they feel threatened, they’ll chase pets and people, and they’re tough enough to flourish in some of the planet’s harshest places, from the heights of the Andes and the lowlands of Central America to the arid deserts of U.S. Southwest and the chilly coastlines of Alaska. Some make epic migrations between their wintering and breeding grounds: One record-setting rufous hummingbird was tracked more than 3,500 miles from Tallahassee, Florida, to near Anchorage, Alaska.

FLIGHT HAZARDS

At least 17 species of hummingbirds migrate between the U.S. and Mexico, where a small group of researchers spends several days each month monitoring both winter guests and year-round residents.

Their study site, called La Cantera (the Quarry), is a lush oasis on the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s main campus, in the capital city. Buffered from the drone of the traffic and smog in North America’s most populous metropolis, the former rock quarry’s flowering shrubs and babbling creek are a haven for hummingbirds.

At dawn one February morning at the site, Claudia Rodríguez Flores huddled in a winter parka, trying to keep warm in the shade. An ornithology Ph.D. student from Bogotá, Colombia, Rodríguez smoothed her long dark hair away from her face and tugged on a pair of fingerless mittens.

As she arranged a tidy work area on a plastic table with a towel and pliers specially designed for fitting hummingbirds’ pin-size legs with metal bracelets, she gave a primer on the research project, now in its seventh year. “We’re trying to monitor the hummingbird population,” she said. “We catch them with mist nets and band them so we can track their movements and try to understand the structure of the community.” Mist nets are typically made of black polyester mesh suspended like volleyball nets between metal poles. “So far,” she said, “we’ve caught 1,355 birds, about nine different species.”

Heading down a cobblestone path, she pointed toward a shady brook where up to a dozen pixie-like hummingbirds were dipping in and out of the water for their morning baths. I watched in amazement, thinking about the rare treat of spotting just one hummingbird in my garden, a magical fleeting moment, like glimpsing a shooting star. Rodríguez carefully untangled a squawking hummingbird from a mist net. She put the bird into a cloth bag and tucked it inside her shirt to keep it warm.

Back at the table she noted how healthy the bird looked. “He’s in great overall condition, probably just molted,” she said. “And he’s already banded, a recapture—we’ve caught him before.”

She used a magnifying glass to read the code, MX8165, on the bird’s tiny anklet and fed him some sugar water through a dropper while taking measurements and dictating to a student who was recording the information. “Adult berylline hummingbird, male,” she said.

The berylline, locally abundant and aggressive, is the most common species found at La Cantera. “They’re the chief of the feeders,” said Maria Del coro Arizmendi, who'd stopped by to see how things were going. They’ll bully and chase other hummingbirds trying to feed.

Arizmendi, 55, fresh from an early morning workout, in leggings, a black fleece jacket, and purple running shoes with fluorescent orange laces, is the preeminent hummingbird expert in Mexico. She’s spent more than 30 years studying the birds and their threats. “Fifty-eight species are found in Mexico,” she said. “Thirteen are endangered, and five are threatened.”

Endemic hummingbird species confined to niches of habitat are particularly vulnerable to environmental hazards. The thumb-size short-crested coquette is found only in the forest edge along a roughly 15-mile stretch of road in the Sierra Madre del Sur mountain in southern Mexico. Now a war zone for drug cartels, peasant guerrilla fighters, and government militias, the area is too dangerous for biological surveys, and as a result very little is currently known about the bird’s status. BirdLife International, a nonprofit conservation group, estimates that the coquette is likely declining by 10 to 20 percent a decade as forest habitat is replaced by coffee plantations and other crops, including opium poppies.

Another threat: climate change. As global temperatures rise, the flowering periods of salvias and other important nectar plants for hummingbirds are shifting earlier in the season, becoming increasingly out of sync with the birds’ foraging demands. It’s a serious concern for migratory species that need to find food at pit stops along their routes. “They fly for a day, refuel, then fly for a few more days,” Arizmendi said. If the flowers continue the trend of blooming earlier and earlier, the hummingbirds will eventually go hungry.

When I asked her about the threat that wildlife trafficking poses to the hummingbirds, she said, “Nobody has a measure, but if the trade for love is growing, we have to stop it now.” She’s concerned about the effects of indiscriminate collecting by poachers (“without any knowledge—females, juveniles, whatever they find”) on those populations of endemic species that are confined to small areas.

By now the table was crowded with students and volunteers shuffling bird guidebooks, pencils, walkie-talkies, clipboards, and data sheets. Carlos Soberanes González, 38, who co-leads the fieldwork with Rodríguez, returned from a final net check. With the morning’s hummingbirds banded and released, it was time for Soberanes, Rodríguez, and me to go meet a Santero priest at a coffee shop near the center of the city.

“MADE IN MEXICO”

I’d imagined a Santero might be an old guy wearing an ornate robe or something exotic, but Arturo Frausto Iwori Ogbe (“Nicho”), 25, came dressed in a black T-shirt, puffy green vest, tan pants, and black Nikes. At Starbucks, sipping a venti caramel macchiato, he prepped us for our visit to the market, where he buys supplies for religious ceremonies, including animal sacrifices. We would talk to some merchants selling dead hummingbirds, Nicho said. “But no pictures—unless I say it’s OK.” (I’d been forewarned that this was no place for tourists.)

Nicho’s religion is Yoruba, named for one of Nigeria’s main ethnic groups, an African faith now commonly followed in Cuba, the Caribbean, Latin America, and some parts of the U.S. Traditional Yoruba beliefs hold that all people possess a destiny or fate and that eventually people become one spirit with a divine creator and source of all energy. The hummingbird plays an important role in this religion as a power force and as a messenger between the spiritual and physical realms.

At the market, every second shop brimmed with dream catchers, voodoo dolls, candles, animal skulls, and Santa Muerte statues. Nicho took us straight to a “witch,” a stocky woman in a green camouflage apron and combat boots. She welcomed us into her shop, where skulls and feathers dangled from the ceiling. Stretching out her palm, she showed us four inert little hummingbirds.

“It’s for amor,” she said—a love spell. “When you do an amor of this kind, be careful because, it’s a big deal. The force of a hummingbird is very strong in the mystique world.”

Then she explained how she makes the spell. “We put them face-to-face [a male and a female bird], ideally with underwear from both a man and a woman. Then you put them in a small red bag, fill the bag with pure honey, and you place it in your shrine with candles. That’s the way we do it.”

Without the honey and other trappings, a hummingbird can be used as an amulet, she continued—“for good luck, or a road opener. If you have someone in your sights, you just write their name, wrap it toward you, and carry it around. Every day you put some of your perfume on it.”

These birds, she explained, were from a guy in Pachuca, the capital city of the state of Hidalgo, north of Mexico City. “They throw nets up to the trees and catch them and preserve them in hydrogen peroxide,” she said. “That way they don’t fall apart, or lose their feathers.” A single bird costs 50 pesos (about $2.50), a tricked-out amor, 600 pesos. She makes about 20 of those a month, mostly for women. “Works 98 percent of the time,” she said. “Very powerful.”

Deeper inside the market, Nicho stopped to say hello to other merchants who showed us their hummingbirds. In one area, where seemingly endless cages of puppies, rabbits, chickens, parrots, and a dead chinchilla lined the aisles, we met a guy displaying a handful of dead hummingbirds. He recommended them as a good treatment for epilepsy or heart problems.

“You cut their heart out,” he said, “and boil it to make tea or soup.” One of the species in his hand was an amethyst-throated hummingbird, noticeably larger than the other species we’d seen. Recognizing our interest in the bird, he offered it for 150 pesos. To sweeten the pot, he’d toss in two free teeth that he said were crocodile.

Almost every vendor we met had nearly a dozen hummingbirds dangling like charms on hooks, red thread stitched through their eyes and throats. Soberanes, who’d worked in pet shops and aquariums as a child and studied military macaws in Oaxaca’s Sabino Canyon in graduate school, touched them in disbelief. He whispered, “These are the birds we try to preserve. It’s very depressing.”

ONGOING INVESTIGATION

At the Fish and Wildlife Service’s forensic lab in Oregon, Pepper Trail was stooped over a black countertop, poking at a petrified hummingbird with a scalpel. He’d found another clue in the chuparosa mystery: tiny orbs visible on a CT scan. Curious, he’d x-rayed some specimens collected during the Delgado case and was examining them now to see if there were any signs of how the birds had been killed, one of the mysteries bugging him.

Removing his glasses, he pulled on a magnifying visor to get a better look at the birds. At first he found only a dried resin-like substance. He noticed that the birds’ breasts had been cut open but couldn’t find any metal inside them. The lab’s veterinary pathologist, Tabitha Viner, offered to take a look. Minutes later she extracted a dull-gray metal ball about the size of a pinhead from the bird’s chest.

“It looks like lead,” Trail said. “Maybe some kind of shot?”

He scraped the fragment into an envelope and took it down the hall to his colleague, Pam McClure, an analyst in the chemistry lab. "Yes," she said, as the results showed on her computer screen. “It’s lead.” Comparing it to a chart of ammunition sizes, she surmised that it was size 11 (1.57 millimeters in diameter), probably something used in a small-gauge shotgun.

Using a shotgun to bring down a hummingbird seems like chopping a salad with a machete. Yet more than a third of the birds Trail X-rayed recently contained lead shot. How they weren’t blown to smithereens is another mystery.

Pedro Trinidad, who grew up in the mountains outside Mexico City and is now living in New Jersey, told me that as a six-year-old, he and his brothers killed hummingbirds with slingshots. It helped pass the time, he said, when they were minding the family cows. He regrets it now, but back then it was what boys did. “Rabbits, snakes—if it moved, we killed it. I could shoot two or three hummingbirds in a day. A man in a local shop would buy them. We’d be very happy because we had a couple of pesos to buy a Coca-Cola or a sweet.”

It would take an army of kids with slingshots to supply the profusion of hummingbirds in Sonora Market and all the botanicas in Mexico and the U.S.

“It comes down to supply and demand,” Trail said. “As long as the demand is strong, people will always try to meet it.”

Stopping hummingbird smuggling will require law enforcement on both sides of the border, but Mexico hasn’t yet determined that there is indeed a hummingbird problem.

Joel González Moreno heads the inspection and surveillance of wildlife, marine resources, and coastal ecosystems in the Federal Attorney’s Office for Environmental Protection. “We have not detected a critical trafficking situation for this group of species,” he wrote in an email. He cited habitat loss as the main concern but added that animal smugglers can face up to three years prison time. And if the smuggling is associated with organized crime, the punishment can be nearly 20 years in a Mexican jail.

Pepper Trail is trying to elevate the issue with Mexican officials. Each year Mexico joins the U.S. and Canada at a trilateral meeting to coordinate international conservation efforts. In preparation for the meeting on April 9, Trail submitted an update on the chuparosa trade.

“Ongoing investigative work by the [Fish and Wildlife Service] Office of Law Enforcement indicates that this trade is significant and widespread, at least in the border states,” he wrote. “Continued efforts need to be made to gather information on the status of hummingbird populations in the U.S. and especially Mexico …. It may be appropriate to consider whether additional protections for hummingbirds under Mexican law are needed …. Additional collaborative work needs to be done involving both governmental and non-governmental organizations in the U.S. and Mexico to educate the public about the ecological importance of hummingbirds and to discourage killing hummingbirds for these love charms.”

“I received an acknowledgement that it was received,” Trail said. “But there’s no one to push for it—I’m not a member of the delegation.”

Humberto Berlanga, Mexico’s coordinator of the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, an international forum of government agencies and private organizations, is a member of the delegation. Berlanga doesn’t regard hummingbird trafficking as a high priority. “I suspect the market is not too big, and I don’t think it’s affecting any endangered species, but we don’t have the data,” he said. “Those are my general impressions. People are illegally catching and using the birds, but there’s not enough enforcement to limit and stop this practice—it’s sad, but true.”

Lately a steady stream of new evidence has been arriving at the Fish and Wildlife Service’s lab in Oregon: a total of nearly 300 birds representing roughly 20 species so far. The birds are accompanied by at least five variations of love prayers. “They’re all printed differently, and the language is a little different,” Trail said. “My assumption is those presentations imply different producers. That tells us it’s not just one—it could be many.”

Trail might never know—because he aims to get out of the detective business soon. On a bookshelf in his office sits a fat white binder labeled “Retirement Planning.” Last year the lab hired a forensic ornithologist who’ll eventually take his place. Trail is excited about having more time to lead birding tours, write prose, and gaze at living, breathing animals. But he’s not relinquishing the case of the chuparosa just yet.

Rene Ebersole writes about science and the environment for many publications, including Popular Science, Outside, The Nation, and Audubon. Follow her on Twitter and LinkedIn.