Our helmeted hornbills magazine story almost didn’t have any photos of helmeted hornbills in it.

OK, that’s a bit of an exaggeration, but it’s true that we were close to not having enough photos of the bird to fill out the magazine story. When Tim Laman, the photographer, first pitched a story about these ancient-looking birds, he knew it would be a challenging assignment. The birds are extremely rare, shy, and elusive.

“I’ve been pursuing hornbills in the rain forests of Southeast Asia for many, many years,” Tim told me. “One of the reasons I wanted to pursue this story was because in my Geographic hornbills story 20 years ago, I photographed many other species, but I never got any good pictures of helmeted hornbills.” (See the 1999 story, "The Shrinking World of Hornbills," members only.)

It was important now more than ever to try, though. The helmeted hornbill is heading toward extinction because of the booming black market for carvings made from its “horn.” Other hornbills have hollow casques, as their horns are called, but the helmeted hornbill’s is solid and easy to carve into beads, figurines, and intricate scenes, which have suddenly become the thing for a certain subset of wealthy Chinese.

It’s not too late to save the helmeted hornbill, we learned, but to get people to care, we had to be able to show them the bird in all its splendor.

“I knew it was going to be hard,” Tim said. “Twenty years ago it was hard, and now they’ve been hunted so much more, they were even rarer. But it turned out to be even harder than I expected.”

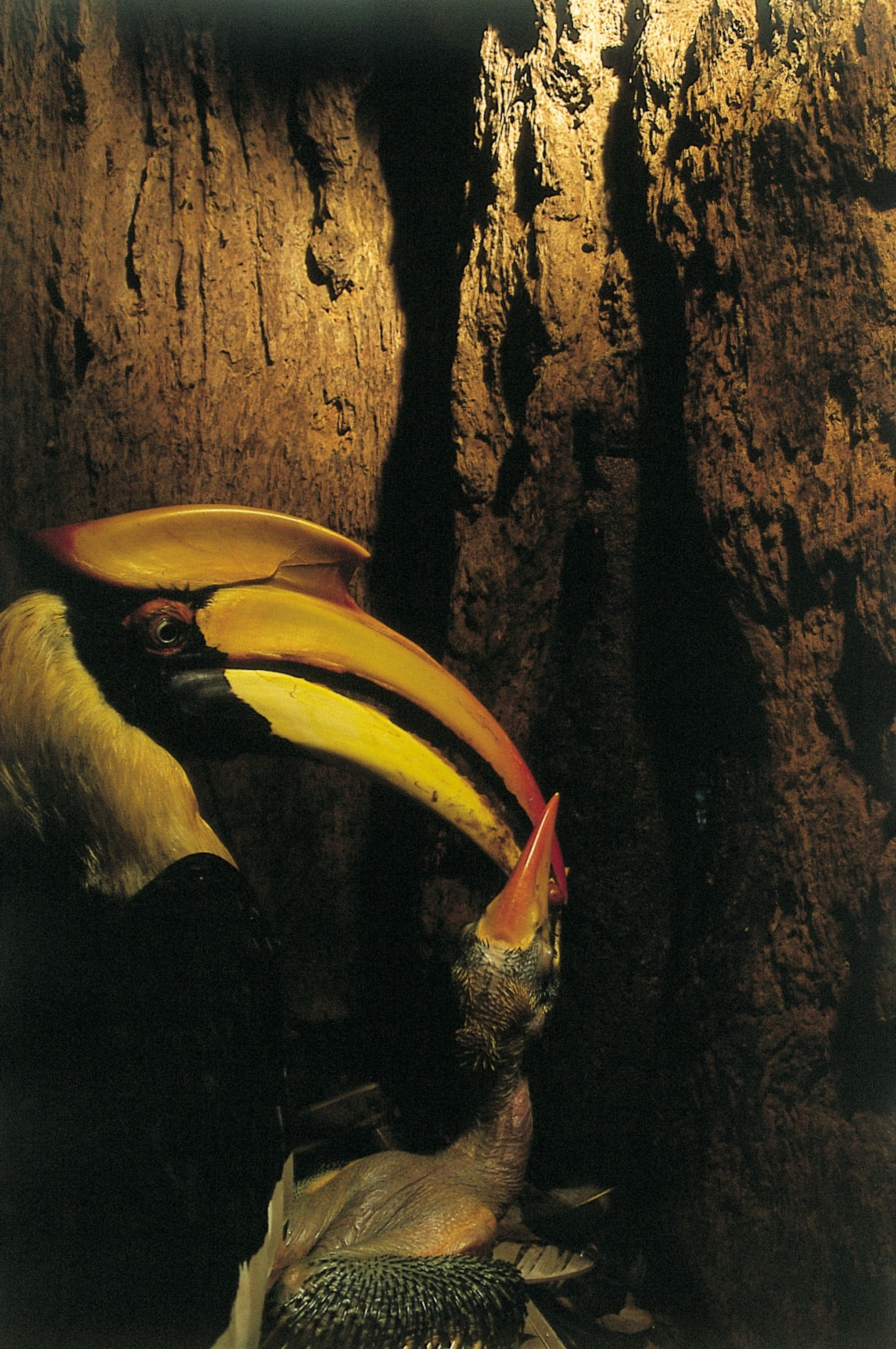

Tim knew our best chance at finding helmeted hornbills would be during breeding season, roughly from March to August. That’s when the female seals herself inside a tree cavity to incubate her egg and raise the chick for up to 150 days, and during that period, the male must deliver them food multiple times a day. If we could spot an active nest, we at least had a chance to see a male.

We were in touch with a research team in Thailand. They recruit former hornbill hunters to monitor and protect hornbill nests—they’re the experts who know which nests are active and how to get to them.

It turns out we were treated to not one, but two, active nests—at the top of a mountain. Suffice it to say it was a very steep, very muddy, very sweaty slog, with a lot of equipment in tow. Tim and I did some quick math, and we figured that with about 15 porters, each carrying 40 to 50 pounds of gear, at least 600 pounds of stuff was hauled up the mountain—the camping equipment, a generator, provisions, and the overnight bags for all the team members. And, Tim says, that’s packing as light as possible, taking just the essentials for a National Geographic-level shoot: His RED digital cinema camera, several Canon SLRs, a set of lenses, a heavy-duty tripod, and a lighter tripod."

I’d never been so thankful to be a writer, needing only a pen, paper, and my own eyes to observe my subject.

Once we got to the first nest site, Tim built blinds for us to hide behind, and we sat there for hours at a time, waiting for papa hornbill to bring a meal to his mate and chick. We often heard his maniacal laughter, seeming to mock us, just a few trees over. Maybe he was figuring out whether it was safe to approach. He lived up to his Latin name, Buceros vigil—vigilant, as in, no matter how well we hid, he always seemed to know we were there.

Still, he did show himself a few times, but so briefly that getting National Geographic-worthy shots was a challenge.

After several days of watching the nest, we got word that a fig tree was fruiting in nearby Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary. It was a chance for us to see helmeted hornbills in a different setting. When fig trees bear fruit, the whole forest menagerie comes to feast, so we had to get there fast to look for hungry helmeted hornbills before the tree was picked clean.

A huge storm broke just as we arrived, but Tim nevertheless managed to build a blind a hundred feet up in a nearby tree. Thankfully he managed to not get struck by lightning. (Watch how Tim climbs a tree here.)

The next morning, and for several mornings after that, we were out at the fig tree by a little after 5 a.m. We hoped that if we were in place before the sun came up, the helmeted hornbills wouldn’t know we were there.

Sitting in the early morning darkness, Tim high above and I on the ground, we heard the night insects quiet down and the screeching day insects start up. We waited as the mist of the night gave way to the humidity of the day. We saw monkeys and giant squirrels, rhinoceros hornbills and great hornbills. But, alas, no helmeted hornbills showed up for some figs.

Ten-hour days in a tree don’t seem to phase Tim. He’s gotten pretty good at making himself comfortable. “I try to make a little seat,” he said. “I have a pad to sit on, and I can move around and stretch a little bit. The helmeted hornbills weren’t cooperative, but there were other birds and monkeys. There’s a lot to watch for, and I was photographing and filming a lot of the time.”

After a few days at the fig tree, we had to move on. I went to Indonesia to continue my reporting, while Tim went back to the first site to visit the other nest. The male helmeted hornbill was less shy at this nest, and he was able to get a few more shots. There still wasn’t a lot of variety though.

“The only images I had at that point were at the nest: The female was already inside, and the male was delivering food. It was great, but it was only part of the story,” Tim said.

Back in the office the team began discussions about highlighting other species of hornbills. If we didn’t have enough photos of the helmeted hornbill...well then, that just showed how elusive and rare they really are, we reasoned. The hornbill family as a whole is fascinating and beautiful, so we figured we could highlight some of the other species to paint a more complete picture of Southeast Asia’s rain forest ecosystem. After all, we did see some gorgeous rhinoceros hornbills and great hornbills.

We had a few more months before the story was to publish, and we were planning one more trip to Indonesian Borneo, a hot spot for helmeted hornbill poaching. We hoped we’d see a helmeted hornbill while we were out in the forest, but we knew this trip was more about documenting the hunting of the bird than actually seeing the bird itself. On this trip there was no time for Tim to hang out for hours on end in a blind. Our hopes weren’t high.

After spending a week with a community of Dayak Iban, an indigenous group, we’d learned a lot about the significance of the bird in their culture and why some of their own were turning to poaching. Then on what was to be the very last day of the trip, we heard from a researcher that his team had spotted a pair of helmeted hornbills scoping out potential nest sites in western Borneo.

It seemed too good to be true. This was the last chance to make photos of the helmeted hornbill for our story.

I had to fly back to Washington, D.C., but the rest of the team quickly got provisions together and headed out to the site, filled with anticipation.

“I was really excited to hear about that location,” Tim said. “It was a unique opportunity to see and photograph a male and female outside the nest. I was happy—and relieved—to get variety so that the entire story could focus on the helmeted hornbill, which was our original intention.”

In the end Tim’s persistence yielded depictions of a range of helmeted hornbill behaviors, including some that had never been documented on film to this extent. And although we didn’t end up needing those other hornbill photos, those birds are so striking that we wanted to share them here.