It's Now Legal to Sell Rhino Horn in South Africa. The World's Top Breeder Makes His Move.

John Hume hopes that holding an auction will help protect the world’s embattled rhinos—and yield a big payoff.

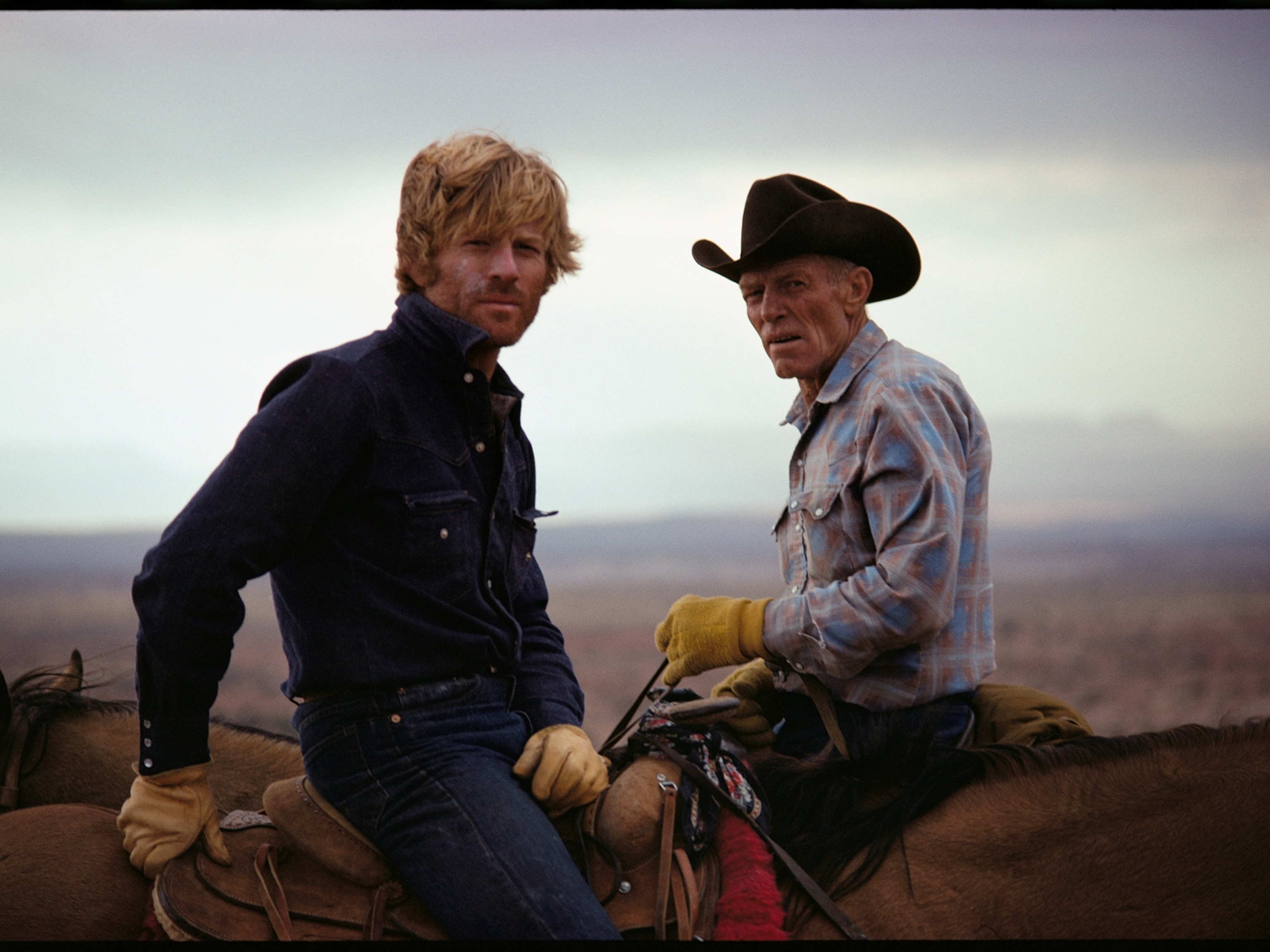

About 1,500 rhinos roam John Hume’s ranch in South Africa’s Klerksdorp, located a hundred miles from Johannesburg. Every 20 months or so Hume, who breeds more rhinos than anyone in the world, tranquilizes the animals and dehorns them. He does this to ward off poachers and for the potential to one day cash in on his more than six-ton stockpile.

That day has finally come.

On Monday, Hume plans to hold an online auction to sell 264 rhino horns to South African residents.

A moratorium on buying and selling rhino horn within South Africa has been in place since 2009, but in 2015 Hume and another rhino horn breeder filed suit to overturn it. A final court ruling in April opened the way for the domestic trade to begin again, though the ban on the international trade, established in 1977, remains in place.

South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs requires anyone who wants to buy or sell rhino horn to apply for a permit. Hume won a last-minute court bid on Sunday to receive his, according to tweets by South African journalists who were in the courtroom.

The stated goal of the three-day web auction is to prevent rhinos from being "poached for their horns in South Africa and to raise money to further fund the breeding and protection of rhinos,” as noted by the website that will host the auction, overseen by Pretoria-based Van’s Auctioneers.

South Africa is home to 70 percent of the world’s remaining 29,500 white rhinos, but it’s in the midst of a poaching crisis. Last year poachers slaughtered more than 1,050 rhinos in the country, up from 13 in 2007. They’re capitalizing on the demand for rhino horn, smuggled mostly to China and Vietnam, where it’s carved into tchotchkes and art and sold for use in folk medicine. (Rhino horns are made of keratin, the same protein found in human hair and fingernails, and there’s little evidence that they have curative value for anything).

Hume spends $170,000 a month on security for his rhinos, the auction website says, plus additional costs for rhino feed and veterinary services. Part of his expenditures go toward trimming their horns.

The concept of selling horn in South Africa has stirred controversy, with most conservation groups opposed to the idea. Critics emphasize that there’s almost no domestic market for rhino horn in South Africa and worry that any horn sold domestically will be trafficked out of the country.

“It’s difficult to see how a domestic rhino horn auction will do anything other than send confusing signals to the rest of the world,” says Ross Harvey, an economist and senior researcher with the South African Institute of International Affairs. “If South Africa’s domestic market is just about non-existent, one has to ask questions about who the buyers at this auction would sell their horns to.”

Opponents are especially concerned about Hume’s auction because it has Vietnamese and Chinese language homepages in addition to one in English. “Clearly Mr. Hume has a broader market in mind, and this calls into question his motive, in my mind, to sell horn,” wrote Joseph Okori, head of the South Africa regional office for the International Fund for Animal Welfare, in a post on the NGO’s website.

Opposition to the auction is so strong that hackers even took down the website last week. “Your lack of common compassion for animals is outrageous and has been dealt with properly,” read a statement on the hacked website, which has since been restored. A group called the National Frog Agency/Central Frog Services, which has the twitter handle @NFAGov, claimed responsibility for the cyber attack.

But Hume, on the auction website, claims that a legal trade in rhino horns will provide competition for the illegal trade and drive down the price of horn, which can fetch $3,000 a pound on the black market in South Africa. The auction, however, will have no set opening price, Johan Van Eyk, of Van’s Auctioneers, told Agence France-Presse, according to Phys.org.

“We will have to look at what people are willing to pay and that will give us an idea of the price on the legal market,” he said. The 264 horns he’s putting up for sale could weigh as much as 1,100 pounds.

The South African government insists that protections are in place to prevent horns from leaking onto the black market. “The department places value on the need to monitor the movement of the horns, and for this reason systems are in place to enable us to do that,” reads a statement issued on August 17 by Edna Molewa, environmental affairs minister.

She pointed to the permitting system, marking requirements, a national database for rhino horn, and a required DNA profile of each horn as examples of how the government will keep track of the horns.

Hume also has plans for a physical auction of rhino horn in September.

Read more stories about wildlife crime and exploitation on National Geographic’s Wildlife Watch. Send tips, feedback, and story ideas to ngwildlife@natgeo.com.