Poachers Work Across Borders, So Why Not Conservation Efforts?

A new study finds that three-quarters of African savanna elephants cross country borders, but the treaty that protects them from the illegal ivory trade doesn’t account for that.

Elephants can travel up to 50 miles a day. And because the majority of them live near national borders, that means an elephant that begins its evening in Botswana may be in Angola by the morning.

Here’s the catch: Angola’s elephants have greater protections under international law than Botswana’s. In fact more than half of Africa’s elephants live in border regions where as soon as they cross that arbitrary line, the level of protection they have changes.

That’s according to a new study in the journal Biological Conservation in which researchers analyzed savanna elephant population data to demonstrate the importance of “transboundary” conservation efforts—when governments and organizations cooperate to manage and protect migratory elephants regardless of political boundaries.

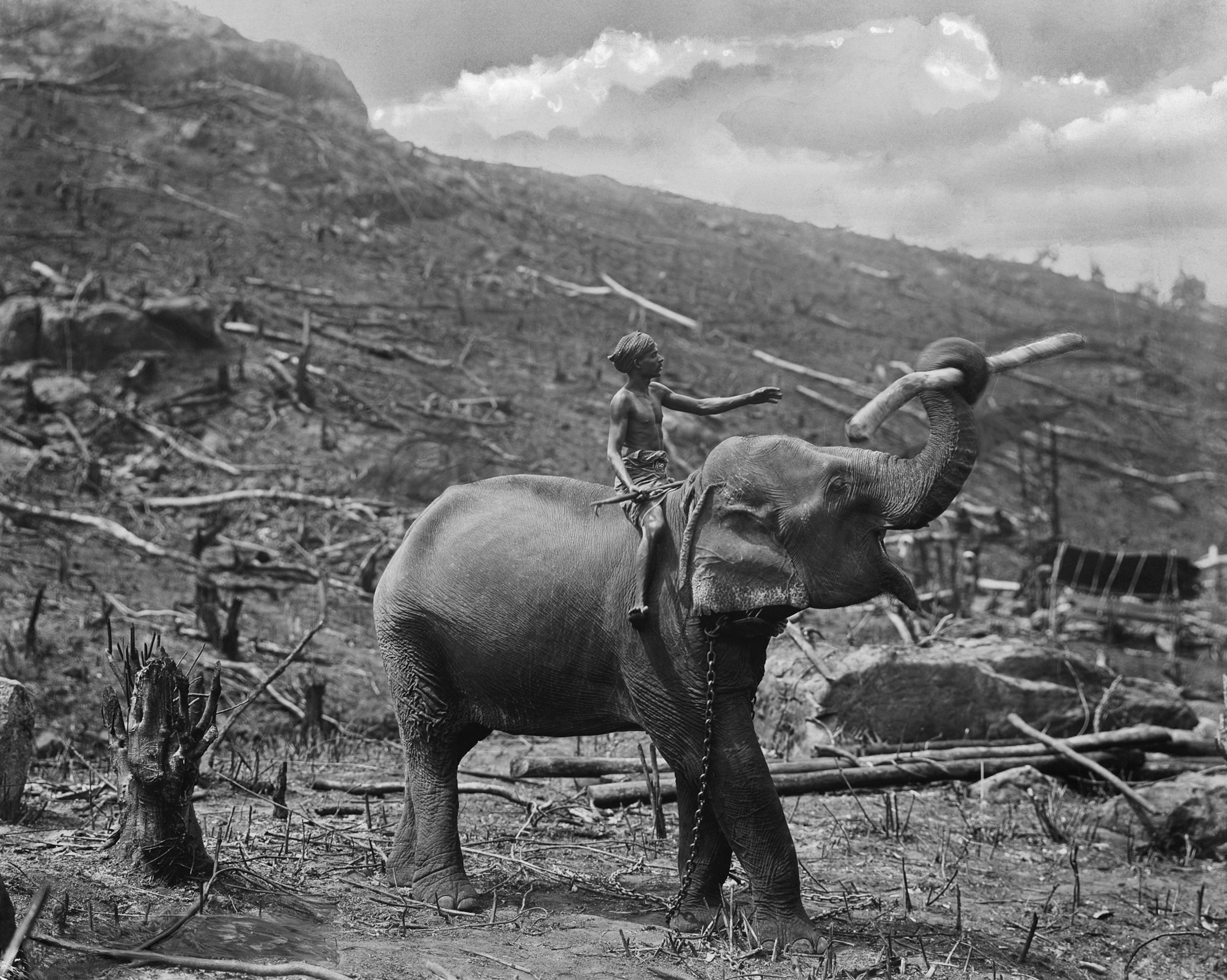

African elephants face serious threats from poaching for the illegal ivory trade. Some 27,000 savanna elephants are killed each year, leading to a 30 percent decline between 2007 and 2014, according to the Great Elephant Census. A ban on the international commercial trade of ivory went into effect in 1990, but there’s a thriving black market to meet demand in China, Japan, the U.S., and elsewhere.

The problem with that ban, according to many conservationists, including this study’s authors, is that it led to a two-tier system in which elephants in some African countries get more protections from the ivory trade than elephants in others. In 33 African countries, the ivory trade is outright banned because elephants are listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the treaty that regulates international wildlife trade.

CITES is one of the most important international treaties for protecting elephants from poaching, and Appendix I is the highest level of protection from the wildlife trade a species can get. But another four African countries—Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe—have their elephants on Appendix II. That listing entails a temporary (nine-year) moratorium on the re-opening of the ivory trade. Last year, however, while the moratorium was still in play, Namibia and Zimbabwe applied to CITES to have ivory trade restrictions lifted, a request that was denied. After the moratorium ends next month, they can make the request again and, with CITES permission, hold ivory sales.

Katarzyna Nowak, one of the study’s authors and a researcher with the University of the Free State, in South Africa (and an occasional National Geographic contributor), and her colleagues argue that giving Africa’s elephants two separate levels of protection from the ivory trade depending on what country they’re in doesn’t make sense because the majority live in populations that straddle national borders.

Therefore, they argue, the best way to protect elephants is by taking a transboundary approach—one that treats elephant populations as shared across regions rather than belonging to one country or another based on the animals’ particular location at any moment.

That, Nowak says, means granting them all the same level of protection under international agreements like CITES. “If a species is highly mobile, then we have to adjust the scale of our management policy to that.” (Read more: A national park in Botswana is struggling to support the staggering number of elephants fleeing from poaching in other countries.)

Plus, she adds, poaching groups don’t care about national borders. They operate across the continent. “Conservationists need to be more, not less, coordinated transnationally than poaching groups,” Nowak says.

Cooperative Conservation

Many other species are managed cooperatively by all the countries the animals pass through. Take migratory birds in the North America. Many native species were verging on extinction at the turn of the 20th century. The trade in native North American birds was booming so well-to-do women could wear plumed hats and hats topped with stuffed birds. In 1916 the U.S. and Canada signed the Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds, which later underpinned the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the U.S.’s first major environmental law. It ensured that birds traveling across the continent were afforded equal protections from hunting, the feather trade, and egg collection, regardless of which side of the border they were on. In the years that followed, Mexico, Japan, and Russia signed similar treaties with the U.S. to make sure birds were protected throughout their migration routes.

Various similar agreements around the world exist to manage migratory species, most notably the Convention on Migratory Species, which focuses on protecting species everywhere they live and move. But it doesn’t focus on trade, which is one of the biggest threats to elephants.

In another effort to protect Africa’s elephants cooperatively, five southern countries banded together in 2012 to create a conservation area that transcends national borders. The idea behind Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area, or KAZA, was to create a space for animals to recover from decades of decline and to promote sustainable human development. That too, however, doesn’t deal with the trade issue.

What the study’s authors ultimately see as most important for elephants in terms of transnational cooperation is getting countries to agree to give all African elephants the highest level of protection under CITES. The prospect that a handful of countries could revive the ivory trade is enough to pose a threat to elephants, according to Nowak.

“The prospect of trade, or the anticipation that a trade can open up, can in itself encourage illegal activity,” she says.

At last year’s big wildlife trade meeting in South Africa, a vote was taken to give the elephants of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe the same CITES Appendix I protections as the other 33 African countries that have elephants. Those countries and Botswana, voted in favor of it. The other three southern African countries, as well as the U.S. and EU, voted against it.

The U.S. worried that the southern African countries would simply “take a reservation,” or formally ignore, the ivory ban if it passed, which is allowed under CITES. The EU argued that some African countries’ elephant populations were too robust to qualify for more protection. And Namibia, Zimbabwe, and South Africa want to maintain the possibility of a legalized ivory trade. (Learn more about the vote here).

Nowak is frustrated. “The forces behind [elephants’ decline] are beyond the control of any one country, but you cannot get CITES to think beyond the national level,” she says. “It’s about cooperation and diplomacy as much as it is about conserving elephants.”