What Discovery of Oldest Human Poop Reveals About Neanderthals' Diet

Fecal fossils reveal meat-loving Neanderthals also ate their veggies.

Want the real poop on the Paleolithic Diet? Discovery of the oldest human fecal fossils, some 50,000 years old, suggests that Neanderthals balanced their meat-heavy diet with plenty of veggies.

Ancient human cousins of our own species, Neanderthals disappeared from Europe some 30,000 years ago, around the time that modern humans arrived there. Long seen as strict carnivores, they hunted mammoth and reindeer, as evidenced by bones left at their campsites. (Related: "Last of the Neanderthals.")

However, Neanderthal fecal samples reported in the journal PLOS ONE on Wednesday suggest that they also ate plenty of berries, nuts, and other vegetables.

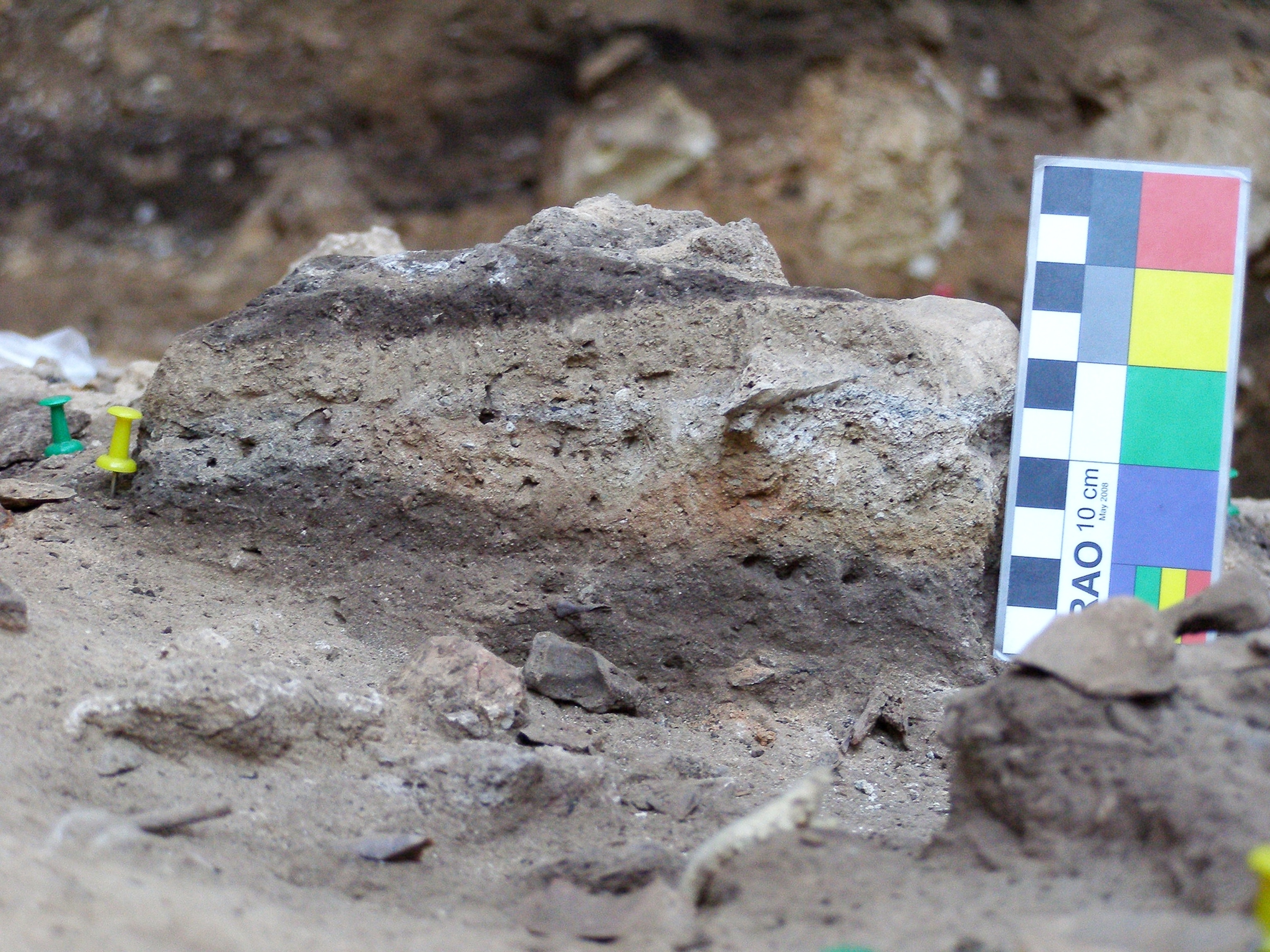

The oldest poop samples turned up at the site of El Salt, a collection of ancient hearths in southern Spain. The researchers were originally investigating the fire pits for chemical traces of fats from cooked meats. Amid the search, they unexpectedly found some fossil feces, or coprolites, in a top hearth layer dated to 50,000 years ago.

"I was quite surprised we found these samples in a place where they would eat," says MIT geoarchaeologist Ainara Sistiaga, who led the study. "We think they were deposited after they stopped using the fire pit."

The previous record holder for oldest human coprolites unearthed by archaeologists came from Oregon's Paisley Caves and are dated to perhaps 12,300 years ago. Far older fecal samples from dinosaurs and ancient sharks have also been uncovered by researchers.

Dietary Surprise

For clues to the Neanderthal diet, lab samples of the feces were pulverized and examined for spectroscopic identification of their chemistry. In particular, the researchers looked for compounds created when bacteria aid digestion of meat and vegetables. (Related: "Hot Stew in the Ice Age?")

The results identified four fats associated with meat. But two cholesterol-related compounds that are an unambiguous fingerprint of plants also turned up.

"They were eating a lot of meat," Sistiaga says. "But we believe they were omnivorous."

Although the chemistry analysis cannot specify which plant foods Neanderthals were eating, pollen analysis suggests that berries, nuts, and tubers grew in the region when the archaic humans lived in Spain. (Related: "Bonanza of Skulls in 'Pit of Bones' Changes View of Neanderthals.")

Mammoth, reindeer, and red deer bones widely found at Neanderthal sites had led paleontologists to see them as dedicated meat eaters. But more recent studies that uncovered plant remains at Neanderthal sites, on their tools, and even in their dental plaque had hinted that they were not strict carnivores.

The present study is the first to provide direct chemical analysis that Neanderthals ate vegetables—the most interesting part of the study, says paleontologist Erik Trinkaus of Washington University in St. Louis, who was not part of the research.

"Their results are confirming an idea that is still somewhat new in the field," says paleobiologist Amanda Henry of Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. But she cautions that more evidence showing that the fecal samples undoubtedly came from Neanderthals, and not from another omnivorous animal such as bears, would be reassuring.

Sisiaga's team argues that the digestive compounds found in their analysis are present in ratios found only in humans. But Henry says by email that their argument would be bolstered with a deeper analysis: "I think the paper would have been stronger if they had used an independent means of identifying the coprolite, perhaps looking for human DNA or proteins."

The compounds tested for in the El Salt study are "very stable," Sistiaga says. "We are going to try a two-million-year-old sample from another site next."

Neanderthal Extinction

Some researchers have suggested that the Neanderthals' meat-centric diet may have left them open to extinction when they were forced to compete for resources after other omnivorous early modern humans entered their territory, bringing more complex tools with them.

That story looks a little too simple now, even if Neanderthals did have a "meat-dominated" diet, according to the study.

Sistiaga suggests that Neanderthal digestion worked with the help of bacteria similar to the ones at work in our own guts.

The coprolites also revealed that the Neanderthals apparently had parasites, such as hookworms and pinworms, similar to the ones afflicting modern and other ancient people. (Related: "Dangerous Parasites.")

"We were told that people with [as] many parasites as we saw [in the samples] would be very sick," Sistiaga says.

Follow Dan Vergano on Twitter.