Billions Have Been Spent on Technology to Find IEDs, but Dogs Still Do It Better

These working dogs have saved countless soldiers' lives—and helped prevent PTSD.

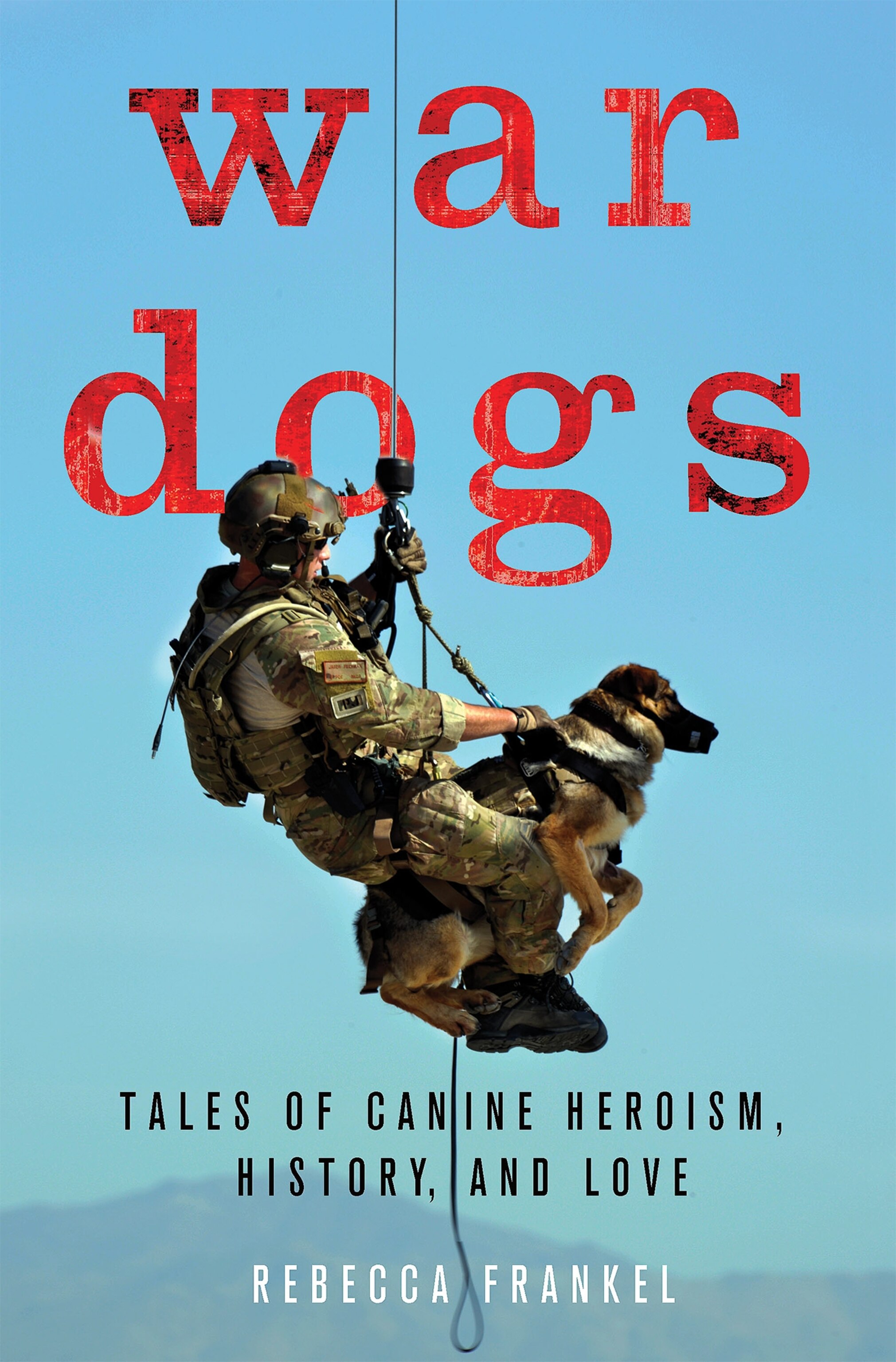

Next Tuesday, Veterans Day, is a time to show gratitude to all the soldiers who've helped keep America safe, including the furry, four-legged ones. In a new book, War Dogs: Tales of Canine Heroism, History and Love, Rebecca Frankel shows that dogs, with their legendary sense of smell, remain the best at finding improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Frankel was given unprecedented access to America's canine heroes. She spent years visiting bases where the dogs are trained, meeting their handlers, watching their charges hone their detection skills. Here she talks about what happens when you don't earn a dog's trust, why these dogs appear to love their work, and what they do in their golden years.

What makes these dogs heroes?

It's the impact these dogs have—they change the way soldiers experience war. It's hard to calculate the exact number of lives they save, but one handler shared his method of calculation with me: If one dog found one IED, then at least one marine's life would be saved, and that's enough for him. I like that equation. (See: "Dog Held Hostage by Taliban Part of Long Line of Combat Canines.")

You've gotten unprecedented access to U.S. military dogs. How did this come about?

I got lucky because of the people I met. One of the first was Chris Jakubin, who was the kennel master at the U.S. Air Force Academy, in Colorado. I talked to him about potentially doing a bigger story and asked if I could come and hang out at the kennels with him sometime.

He agreed, and I spent a week. But it wasn't just me hanging out. Chris planned my days, from 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. Chris is very connected in the dog community, because he's been doing it a long, long time. He introduced me to everyone, and because of his great reputation, his introduction gave me a foot up. I was able to shed the public affairs officers and kind of cut the line. Instead of being a reporter, I was able to just be someone able to hang out with the handlers. (See: "The Dogs of War.")

Can you talk a little bit about what you saw at the kennels? What was dog training like?

What became very clear to me is that if you don't see the teams in action, it's really hard to glean what the dog teams are capable of by just reading about them. When I was at the Buckley Air Force Base, in Colorado, with Chris, I had the opportunity to do a search with a dog named Haus.

I was told I had to "clear" a bathroom. Haus and I walked into the bathroom, and I gave the command to seek, because that's the way they did it in training. At first when I said, "Seek," and put my hand out, Haus followed me, and I thought, We're doing it!

Then we got to the bathroom stalls, and it got complicated. I was trying to hold open the door for myself and a dog on a leash that's used to moving very fast. I was trying to guide him around the toilet, but the leash got all tangled up in the toilet, and then I got tangled up. Then the door hit me in the back, and Haus skipped a stall, and I had to pull him back.

The whole time he kept looking back at the door as if to say, Guys, why are you out there, and why am I in here with her? [Laughs.] He didn't know me and didn't trust me. Finally in my head, I said, I can't do this.

And literally the minute I had that thought, Haus sat down and gave up. He knew I was flustered, and he didn't trust that I was leading him in the right direction, so his attitude was, I'm not going to work for you—you have no idea what you're doing, lady!

It turned out there was a mock explosive in the bathroom. The sergeant brought me back to the starting point and showed me that right at the entrance of the bathroom—if I'd had just scanned the room myself first—I'd have seen that there was this huge piece of masking tape across the paper towel dispenser. If I'd looked at it, the dog would have found it. It was a lesson for me that the handler is the anchor, and the guide and can't just sit back and let the dog do all the work.

So that didn't go exactly as planned. Can you tell us how a dog like Haus is supposed to act when searching for an IED?

The handler says, "Seek," and sticks a finger out to guide the dog's nose, and together they check any and all things they can see. When the dog smells something, he does something called alerting, which means they sit down to alert their handler. (See how a handler and her dog defied the Army's expectations.)

They're trained to sit because it's a very physical signal that can be done without noise, but also because if the dogs are "on odor," it usually means they're close to an explosive, and you wouldn't want the dog to move any closer to it.

It's also a helpful signal because they can be working off leash at a distance of maybe a hundred yards, but even then you know when they find something, because you can see them sit.

As a handler, you spend enough time around your dog that if you are close enough to your dog, you can tell just by the way your dog sniffs. The dog will get really excited, and they sniff very quick and very deep. This is a reason why it's so important for dogs and handlers to be closely bonded, because a good handler who really knows his dog is going to know before the dog gives his final alert. (See: "Dogs at War: Caesar, One of the First Marine Dogs in the Pacific.")

You mention the importance of a strong bond between handler and dog, but hasn't it been said that the military views the dogs as equipment?

It's not true. There were op-ed articles published in USA Today and National Review that I think were preying upon the emotions of its readers when they said the military treats its dogs like equipment.

There are, however, handlers and trainers who think it's a mistake to become too attached to their dogs and put love in the equation. I was very surprised by this. It might be because it's the military, or how the program evolved, or because love is seen as unacceptable and too soft—that a certain kind of love and affection compromises a dog team's ability to work in the heat of combat. The fear was that handlers might make a wrong decision because they'll try to protect their dog, or they won't want to put their dog in harm's way.

Talk about the effectiveness of these dog teams. Why are people still using dogs rather than some kind of fancy IED detection technology?

I think the answer simply is that for bomb detection, dogs work better, and their track record is stronger. In 2010 Lt. Gen. [Michael] Oates gave a report on how many billions of dollars had been spent on creating new technology to battle IEDs. And after all the money they spent and the new things they'd developed, they found that dog teams were still the most effective method.

This is sort of baffling, because you step back and then ask why more money isn't being spent on dogs. Perhaps the answer is that it's easier to lobby for money when you're talking about something that can be invented and created anew rather than something like a dog—already superior as they are.

If they can find something better than a dog team, it would be worth spending the money, because we're talking about saving peoples' lives.

You refer to them as working dogs. Could it be argued that these dogs lose out on having a carefree life?

Chris Jakubin said that they get a lot of flack from organizations, like PETA, that call their training of military dogs animal abuse.

After he said that, I didn't watch what Chris was doing—I was watching how the dog was reacting. And at no point did the dog seem to be uncomfortable or put at a disadvantage. The dog seemed to want to be there.

I've observed so many of the dogs and watched them train, and I don't think most would be happy house dogs. These dogs delight in their work. They put their gear on, and they're ready to work. You can see the change in them. They want to be doing what they're doing—their ears perk up, and their eyes light up.

After all their hard work for this country, what happens to these dogs after their military career?

Usually the dogs become celebrities in their own right, so people go to pay tribute and give thanks to the dog. There's actually a very lengthy retirement process. A veterinarian, the kennel master, and an animal behaviorist determine if the dog is in good enough health to be retired, if he has the right temperament, and if it's safe to put him in a home environment. (See: "War Dog Helps Family Cope.")

The waiting list to adopt a military dog is over 1,200 people. But oftentimes they go to their handlers. Actually a bunch of dogs I wrote about have since retired and now live with their handlers.

I think this does a lot of good for both handler and dog. I think it means a lot for the dog to be with someone that they know, trust, and love. One handler told me that he began sleeping better and feeling more relaxed when his dog retired and came home with him.

You met so many dogs, trainers, and handlers while doing your research. Are there any stories that particularly stand out?

In chapter eight I talk about an effort to deploy "combat and operational stress control" dogs. They trained a few Labradors that were deployed with units that are basically occupational therapists, with the goal to help prevent PTSD by using canine therapy during deployment. (See: "Dogs at War: Smoky, a Healing Presence for World War II Soldiers.")

This one handler I interviewed had this really amazing story. She arrived with her dog, Bo, in Baghdad right after the day of the Camp Liberty shooting, which had been devastating. The New York Times called it the worst soldier-on-soldier violence since the war had begun. She was there for 15 months, and she told me about the positive impact having the dog made.

When they arrived that first day, the woman who picked them up told them she didn't think any of the soldiers would want to talk to her, because the soldiers were [mentally] in a bad place.

Once they got there, one of the majors asked them to stay in the room with them. Boe was tired and wasn't wearing her vest—her signal that she's in work mode—so she was just acting like a normal dog.

People were calling to Boe from all around the room and petting her. At one point she just kind of plopped down and let out this big grunt and rolled over on her side. And for just a few minutes, the handler said, the people in the room chuckled and laughed. It was a small thing, but it helped.

Follow Ashleigh N. DeLuca on Twitter.