Malala on Standing Up to World Leaders While Also Being a Teenager

Malala Yousafzai has opened a school for Syrian refugees, taken on the president of Nigeria, and won a Nobel Prize. Now, at age 18, her life is a movie, and she has big plans for the future.

Updated February 24, 2016

When Malala Yousafzai was born, the people in her Pashtun village felt sorry for her parents because their new child wasn’t a boy. Now, Malala commands attention as the youngest-ever Nobel Peace Prize winner, advocating for girls’ education.

During her journey to the world stage, she took on the Taliban as an 11-year-old blogger, survived an assassination attempt, and co-founded the Malala Fund, an organization that supports education around the world.

On February 29, He Named Me Malala, a movie about her life, has its television premiere on the National Geographic Channel. (The Channel partnered with Fox Searchlight Pictures on the release of the documentary.) Speaking from Los Angeles, Malala described how she pushes world leaders to act and why she doesn’t think she’s really that special.

What would your life be like right now if you were living in Pakistan without an education?

I would have two or three children by now. I’m fortunate that I’m 18 and I’m still not married. When you don't get an education, your life is very much controlled by others. I would not prefer that life.

The Taliban, when it took over the Swat Valley, wanted girls like you to have that kind of life. What gave you the courage to speak out?

My parents were always there to say that I have this right to speak, I have this right to go to school, I have this right to be myself and to have independence. If other girls in the Swat Valley, including some of my very close friends, had been given this right by their families, we would have been here together speaking out for girls’ right to go to school. But they were not given permission to go out.

What I really mean is that I’m not a special girl who was different than others. There were many girls who were there, who could speak out better than me, who were more forceful than me, but no one allowed them.

Do you ever talk to your friends from home?

I still talk to my best friend.

She must be amazed by how your life has changed.

Yes, but we don’t usually talk about those things. We just talk about our personal life, make fun, joke. It’s totally a time of enjoyment. We don’t talk about meetings with the president or going to Jordan or anywhere. We just try to be like normal friends.

And yet you do meet with presidents and other world leaders. Do they listen to you?

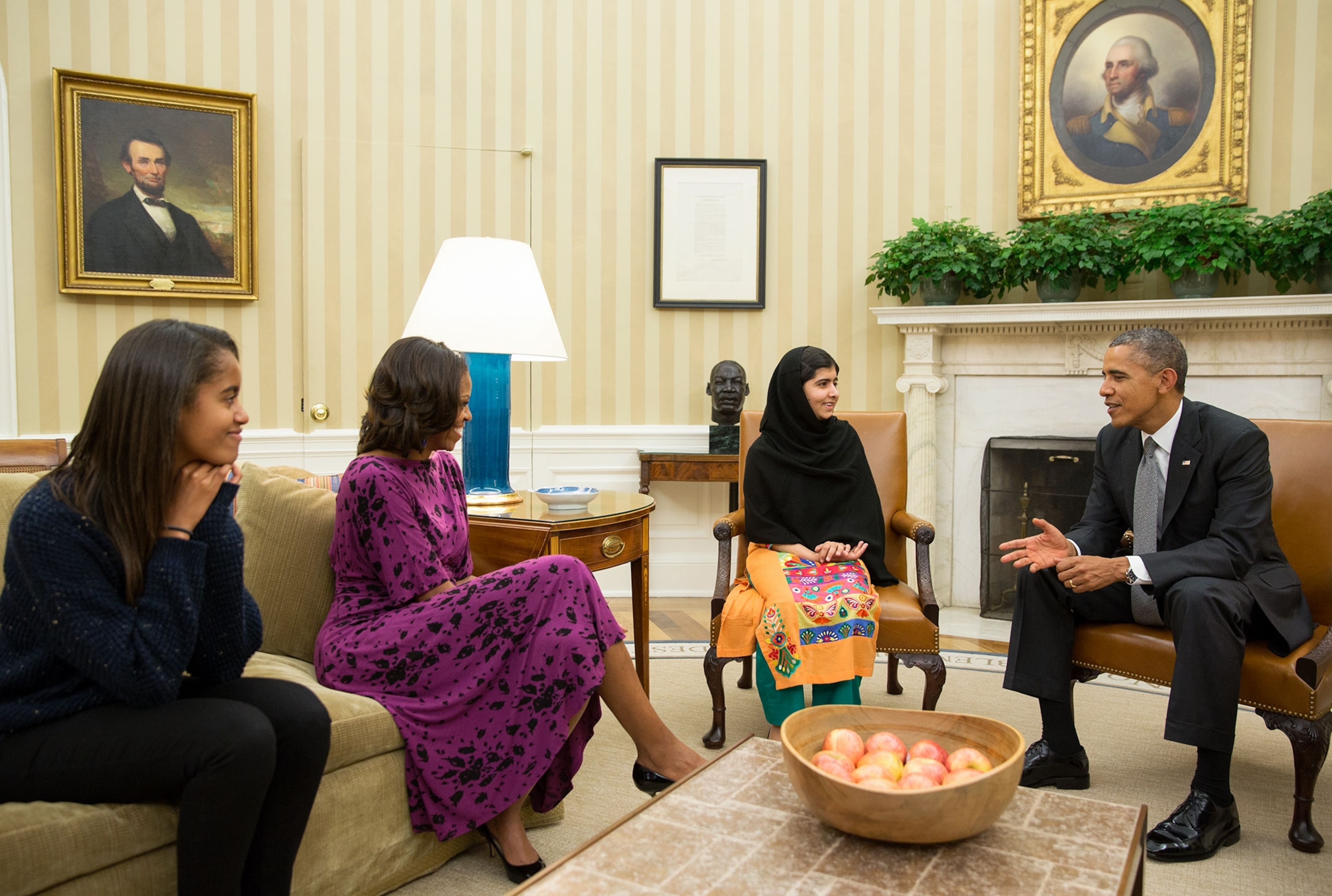

Before a meeting with President Obama, we clearly said that we were not coming to just take pictures. We would highlight some very important issues, if the president was ready. They welcomed us and said you can discuss anything.

You were very critical of the then-president of Nigeria, Goodluck Jonathan, when you met with him last year to discuss Boko Haram’s kidnapping of more than 200 school girls.

It was my 17th birthday. The girls were abducted in April and my birthday was in July, but the president had not met the girls who had escaped from abduction. He had also not met the parents of the girls who were abducted by Boko Haram, and he had given no support. He had not even mentioned the issue.

When I met the president, I said very, very clearly, “You have not met them, you have not given any support to these girls. The world is raising its voice, people are raising their voices. Now you need to listen to their voices. These are your people, your country’s people, and they have elected you. It’s your duty to respond, your responsibility to listen to your people’s voices.”

Children are in the millions in this world. If millions of children come together, they could build up this strong army and then our leaders have to listen to us.Malala Yousafzai

In a few days, he met the parents, and he met the girls who escaped from abduction. He provided some financial support, but no one was really helping the girls, up to 30 of them, who had escaped from the abduction. No one was giving them any scholarships or any school security.

So I thought, What can I do? We provided them scholarships, and now they’re getting an education. You go and you ask the president to do something but if they don’t do it—if I can do it—why not me?

Can other children follow your example?

I think it’s very important that children and kids think that their voices are very powerful. It does not matter what your age is. We should believe in ourselves. All my brothers and sisters across the world should think that it’s important that they realize their responsibilities. If we want the future to be better, we need to start working on it right now.

Children are in the millions in this world. If millions of children come together, they could build up this strong army and then our leaders have to listen to us.

I’m not really a child. I’m now 18. Legally I am not a child, but I am still in that group of children.

When you were younger, you wanted to be a politician. Is that still what you plan to do?

This was during the terrorism situation in Swat Valley when no one was helping us. We were stopped from going to school, and no one was even responding. We became internally displaced, and nothing was really happening.

I thought if I became a politician, I would change everything in my country. It would become a happier and better country. But right now I’m still discovering many things every day. I hope that I’ll end up in the right job and destination.

After you were transported in a coma to England, Gordon Brown, the former British prime minister, gave you a copy of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Do you ever feel like Dorothy, who woke up in a strange land and had to figure out how to get home?

I do feel like Dorothy. She was on her way to go to her home, but she stopped to help others. I want to help people. I want to help children go to school—this is my responsibility.

For me, going home to Pakistan is also about making sure children there get a quality education. My home is making sure all children go to school.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow Rachel Hartigan Shea on Twitter.