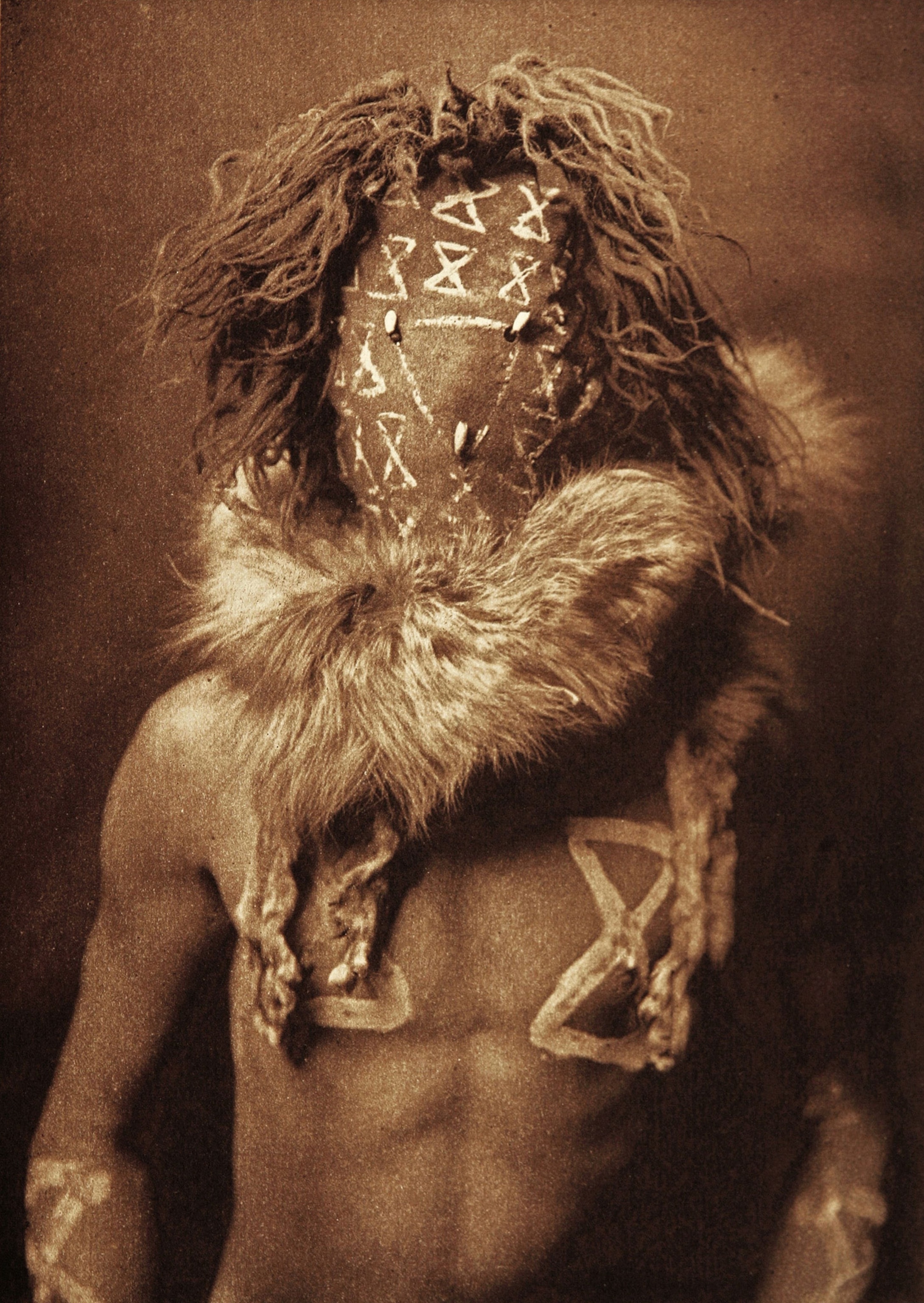

These 12 Photos of American Indians Are Beautiful, Surreal, and Haunting

Edward Curtis defined the way we see Native Americans.

In 1895, photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis met a subject who would change his life and who would forever alter the way we see American Indians.

Her name was Princess Angeline, and she was the daughter of Si’ahl, a powerful American Indian chief for whom the city of Seattle was named. By then she'd grown old, selling clams at markets to make ends meet. He asked to photograph her, paying a dollar per photo—and set himself on a decades-long course to document American Indian life.

Curtis, who died 63 years ago on Monday, became arguably the single most influential chronicler of American Indian culture.

With the backing of J.P. Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt, the photographer dedicated 30 years taking pictures of American Indians from the Arctic to Florida, depicting them as timeless figures untouched by modernity.

“Curtis assigned beauty and romance to the Native American image,” says Alexandra Harris, an editor at the National Museum of the American Indian, in Washington, D.C.

Curtis left behind an unparalleled cultural record of over 80 tribes, comprising some 40,000 photographs and over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of American Indian language and music. His twenty-volume opus The North American Indian, issued from 1907 to 1930, was among the most ambitious publishing feats of its time.

But the photographer's reputation is far from unblemished. “Curtis is a mixed bag,” says James Faris, a retired anthropologist and author of Navajo and Photography. “His efforts and accomplishments were amazing, but he is guilty of some of the errors of his time.”

Some of Curtis’s methods would violate today’s standards for photojournalism. He staged scenes in studios, provided traditional clothing and jewelry to photographic subjects, even retouched photos to remove modern trappings, such as alarm clocks. What’s more, he chose not to document contemporary issues that American Indians faced, such as federal boarding schools meant to assimilate children at the expense of their cultural heritages.

Most of all, Curtis’s work was strongly shaped by the false notion that American Indians were a “vanishing race” whose cultures were doomed to disappear. “Curtis completely epitomizes our society’s myth of the Native American as some static, unchanging thing,” says Harris. “His photos are the vision of reality he wanted others to see, not what was actually real.”

In this gallery we look back at some of Curtis’s best images of ceremonial regalia from across North America. The photographs were scanned from the National Geographic Society’s copies of The North American Indian, which were purchased by Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone and the Society’s second president. In 2012, the originals were sold at auction for over $900,000, raising money for the Society’s archives and support of emerging photographers.